Corrosion Of Conformity spent most of the 80s embedded in the US hardcore scene before pivoting to a more metallic sound with 1991’s Blind album. But it was 1994’s follow-up Deliverance that found them finally reaching a wider audience and getting the approval of metal’s biggest band.

Corrosion Of Conformity (or COC, as they’re more affectionately known) started in Raleigh, North Carolina during 1982. The original lineup featured vocalist Eric Eycke, bassist Mike Dean, guitarist Woody Weatherman and drummer Reed Mullin. However, after the release of debut album Eye For An Eye in 1984, Eric left, the remaining trio going on to record 1985’s Animosity, with Mike and Reed on vocals.

The arrival of former Ugly Americans singer Simon Bob Sinister led to the 1987 EP Technocracy, before the band began to change direction. Until then, the style had a punk/hardcore approach, with hints of thrash. Now, with both Mike and Simon departing, COC went for a heavier, more metal approach. In came vocalist Karl Agell, guitarist Pepper Keenan and bassist Phil Swisher. 1991’s Blind got the band a lot more attention, with the new metal style ensuring that the song Vote With A Bullet became an immediate favourite. But there was further upheaval on the horizon. Karl and Phil quit to form stoner band Leadfoot, Mike returned, Pepper took over on vocals and COC signed to Columbia – in time for 1994’s Deliverance.

At least that’s the simplistic version of events. But the reality behind Deliverance is complex, painful and not a little stressful. That is, if you’re Pepper Keenan.

“Here’s the way it was: we were signed to an independent label called Relativity,” th singer says. “They’d put out Blind, but musically things changed when we started the process for the next record; we’d moved totally away from that hardcore metal scene. We’d written the song Albatross, and had already gotten the Skynyrd vibe going on. The truth is that we were determined to become a different type of band.”

On the advice of The Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan – a fan of the Blind album – COC went to Southern Tracks Studios in Atlanta with the still-incumbent Karl Agell in tow. Teaming up again with producer John Custer (who had worked with them on the previous album), they started working on the basic recordings for their next album. Which is where the problems began.

“We were on a real roll, and things were coming out so well. Then Karl came down to the studio, and it was obvious to all of us that he wasn’t up to the standard we needed. His vocals were wrong, his lyrics weren’t right. We knew it, John Custer knew it. So we made the decision to get rid of him. At which point, Phil Swisher freaked out and quit, which was OK by us.”

At this juncture, COC had very little money. They were working on the sort of tiny budget a small label in the early 1990s could afford to give to a band. This wasn’t a massive project with bottomless pockets. Therefore, the band’s choice to switch vocalists had consequences.

But slowly things began to take a fresh shape. Firstly, Mike Dean elected to return to rejoin COC, which proved to be crucial.

“Mike was living in the jungle somewhere, but got to hear a tape of what we’d done,” says Pepper. “And he liked it. So much so that he asked to come back, which suited us just fine. The first thing we did was play him a track which, at the time, was called ‘The Thin Lizzy Song’, and would later become Clean My Wounds. Mike totally turned it around. He came up with this amazing walking bass line, and everything just seemed to fit into place.”

The first nightmare had been dispersed. But the band were still without a singer, and time was skipping merrily towards the inevitability that money would soon run out. Then Dean made a momentous suggestion.

“I’d been working my ass off writing lyrics. We’d been auditioning vocalists with no luck,” says Pepper. “Then one day, Mike just said to me, ‘Why don’t you sing?’ I’d done the vocals on Vote With A Bullet, so I thought about it, and off we went. The first thing I did was Albatross, and it just came across as being correct. We went from there.”

After working on it for almost two years, finally COC had an album finished. But there was another hurdle facing them. The band did not want to release their lovingly created record through Relativity.

“By then they’d really gone on to backing hip hop bands like 24-7 Spyz,” says Pepper. “We didn’t fit in at all, with our new sound. So we asked them to let us go. They refused.”

It was an impasse that took the sort of turn you’d only find in an improbable movie scripted by a total fantasist on a major acid trip. Enter Columbia Records.

“Somehow, and I don’t know what happened, a tape of the album got to Don Ienna, who was the President of Columbia Records. He freaked out over it, wanted to sign us. So, he contacted Relativity.”

So were the band bought off the indie label and ended up happy ever after with a major company? No, that would have been far too easy.

“Relativity refused to give us up,” says Pepper. “They’d paid for the record, and were not gonna hand it over to anyone. We were stuck. All of us were flat broke, I was living on some- one’s floor, and just as it looked as if things were going our way, we were crippled.”

That might have been the end of the matter, had it not been for one more financial twist of them all.

“One day, someone connected with Columbia said to me, ‘Check the New York Times financial pages.’ I was intrigued, got a copy and… holy shit! There it was: ‘Sony Buy Out Relativity’. Sony, who owned Columbia, had only gone out and bought Relativity and made them a small arm of their operation. I swear, I was told that the only reason Sony had done this was to get the COC album. That sounds fucking insane, but it’s what people connected to Columbia said to me. I called up all the guys, informed them that we were now on a big label, and then went out and got more drunk than I’d ever been in my life!”

After all the agonies they’d been through to get this point, there was finally a light at the end of the tunnel for COC. Their commitment to an album that could have easily ended up doomed more than once was paying off.

“I tell you how bad it got in the studio,” says Pepper. “We’d already paid for the time there when we got rid of Karl. There was no way we’d ever get the money back. In desperation and for something to do, Woody Weatherman, John Custer and I wrote instrumental pieces. We never had any clue what to do with them at the time, but they ended up being ‘interludes’ between the songs.

“When Deliverance was released, everybody thought it was an amazing idea. The truth was that it was simply something we’d come up with to use up studio time we’d already paid for. But that was typical of this album – we did things without realising how far-reaching they might be.”

Deliverance was at last released in late September 1994, and started to create a genuine buzz. Fuelled by the radio success of Clean My Wounds, which also appeared on the soundtrack for Tekken: The Motion Picture, and Albatross, it went on to become COC’s biggest-selling album. Official figures in 2005 put US sales alone at 440,000, just 60,000 short of earning the band a gold record.

“By now it must have gone past that mark,” muses Pepper. “But I still don’t have a gold record on my wall!”

Things were really going COC’s way. They were invited to be part of the bill for the 1995 Monsters Of Rock Festival at Donington, headlined by Metallica.

“Metallica personally chose every band on the bill, so it was a real honour for us to be included,” says Pepper. “We also got to open for them when they played a ‘secret’ warm-up show beforehand at what was then called the LA2 in London. We’d gone from being these broke musicians with no sort of a future to having James Hetfield coming up, as he did, and slapping me on the back, saying, ‘Hey man, great album.’”

For Pepper, the best thing about Deliverance was that, by being utterly determined to do what they believed to be right, Corrosion Of Conformity proved so many people wrong.

“I recall when we had a tape of the songs without vocals, we knew it was the right move to make, even though every- thing was against us,” he says. “That’s what I’m most proud of. At a time when the world was going Seattle crazy, we were listening to classic rock like Grand Funk Railroad, and insisting that’s where wanted to be.

“We’d grown up with Sabbath, but really couldn’t play what they did,” he continues. “That’s why the early stuff sounds like Sabbath sped up! But we got so into the Southern vibe, and we were doing it when it was far from trendy. You could say we began the revival, and gave the idea to so many others.”

The other thing Pepper is delighted about is the way Deliverance severed the last remaining connections with the hardcore scene that had spawned COC a decade earlier.

“We were fed up with that scene,” he says. “It was going round in circles, offering nothing new. But when we came out with this album, so many hardcore bands and fans accused us of selling out. I thought it was laughable. Like what they were doing was true hardcore? I’ll tell you what was ‘hardcore’: COC going onstage and facing all those fans and playing Albatross. That took balls. Tat’s being more true to the spirit of the movement than anybody else.

“Then, 10 years after the album was released, we had all these hardcore dudes who’d publicly hammered us, coming up and asking for our autographs on vinyl copies of Deliverance. They apologised to us for being the way they’d been at the time. That’s what I call vindication!”

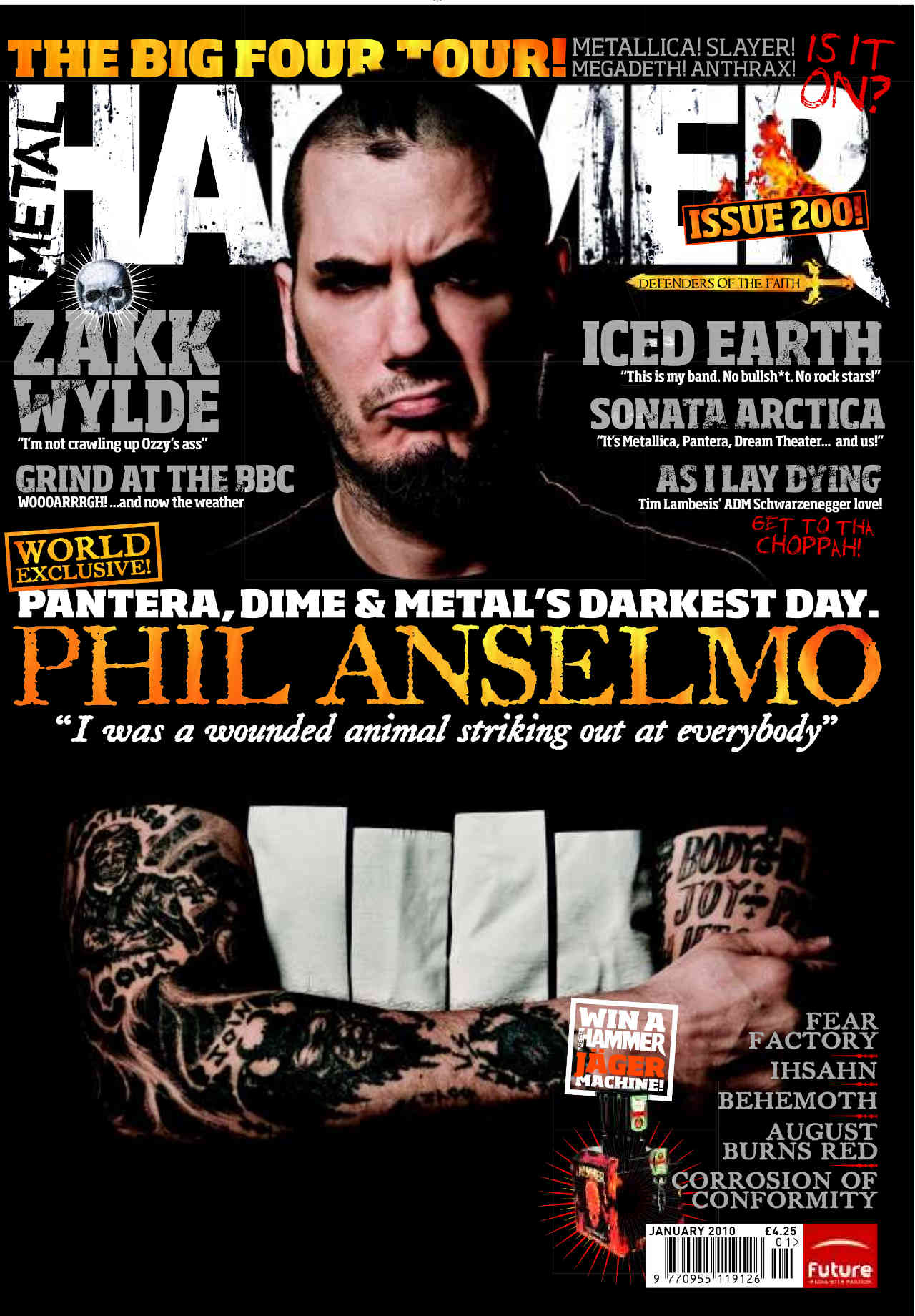

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 200, December 2009