Content warning: this article contains distressing information about Stolen Generations and residential schools. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

Eliza Woods is standing in the native reserve that was her childhood home. Back then, she recalls, love was everywhere:

This was where I first learned about bushfoods from my grandmother, kurup, kumuk, kooting, and little flat-leaved potatoes we dug. Love of our grannies, aunties and parents surrounded us here. We didn’t have many clothes or fancy things, but we were kept clean, fed and loved.

Eliza is a 73-year-old Goreng Noongar Elder. She is visiting the nine-hectare reserve, sandwiched between industrial grain silos, a creek and a main road on the edge of Borden, a small farming town in Goreng Noongar Country in Western Australia. She is here with her cousins, younger family members and non-Indigenous research collaborator, Alison.

To Alison, a conservation biologist, the place doesn’t look like much – small, scraggly mangaart (jam, Acacia acuminata) and quandong trees (Santalum acuminata), a couple of big, old red morrell trees (Eucalyptus longicornis), and a thick ground layer of grassy weeds.

Eliza and her family invited Alison to listen and record as part of University of Western Australia’s Walking Together project. This project brings Noongar Elders, their families and conservation biologists together to share lessons about protecting and restoring Boodja (Country).

In the reserve, weeds smother native plants and make it hard to walk. It looks like a difficult ecological restoration project for minimal reward: weed seeds continuously enter from next door and upstream, and the native species present seem unremarkable.

But what Alison’s science training doesn’t tell her is how central this place is for many Noongar families who have called it home.

On reserves such as this, ecological restoration holds deep personal meaning for First Nations people. For descendants of those stolen, restoring a special family place enables them to reconnect to the past, to people and identity.

Camping in fertile woodland

Authorities allowed Noongar people to camp here from the early 1950s to late 1970s under provisions of Western Australia’s Aborigines Act 1905.

While it wasn’t a chosen home, it was a sanctuary for Noongar families, where kids could always get a damper feed from an aunty, where stories were yarned, where wattle gum and bardies were gathered and eaten, and where campfires were family epicentres.

We know the last 100 years of its history well, but Noongar families have undoubtedly camped in this fertile woodland for millennia.

Read more: Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

Eliza lived on the Borden reserve with her siblings and parents for most of her childhood years, along with most of her mother’s ten siblings and their families. It holds treasured memories.

During the 1950s and 1960s, despite much Boodja being cleared for agriculture and made inaccessible to them, Noongar families could still maintain a rural life, kinship connections and employment on farms. Children could attend school, and families could access basic food and other necessities.

Eliza recalls that Noongar men and women worked hard on farms, burning up and malleeroot picking. Looking around the reserve, Eliza points out one big morrell tree:

that’s where Pa and Granny had a humpy. He was a builder, so he made a little room there from timber and galvanised tin.

And then us kids and Mum and Dad, we pitched a tent near them. They would camp out of town for a job, then come back here. I was 17 when my mum died, and I treasure the short time she was here.

Healing deep wounds

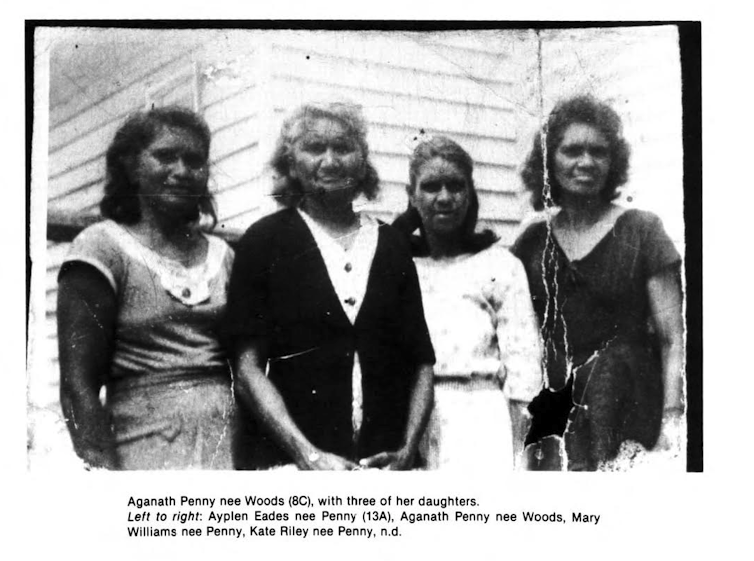

After Eliza’s mother died in 1966, her two youngest siblings were wrenched away, taken to Carrolup Mission 150 kilometres away. So were Eliza’s cousins: Elsie Penny when she was seven, and her little sister.

Operating until the 1970s, Carrolup Mission, later called Marribank, was established in 1915 as part of the state’s assimilation policy to forcibly remove Aboriginal children from their families.

Elsie has some early memories of living on Borden reserve in a tent by the creek with other families in the 1960s.

I remember swimming in the river. We were happy, playing together and we had all our family. That’s what I remember. As kids we just had a lot of fun down the river. We were carefree and felt loved.

Elsie, now in her 60s, has returned to Borden reserve with her children, grandchildren and Eliza to hear stories and begin to heal deep wounds. Eliza describes how it feels to keep coming back to Borden reserve:

it might look like rundown bush but we can write novels of memories made here.

Elsie reflects on importance of knowing where your roots lie.

Without knowing your history, you sort of feel lost. And I guess I did for a while when I was in the mission. We were disconnected then and that’s why we need to come back to where we grew up.

Eliza’s brother, Eugene Eades, had camped at the reserve the previous night to today’s visit and yarned with his nephew Jeremy, saying:

as I lay in my tent, my thoughts went back to those happiest days of my life, living here. A place set aside for blacks, for us to live on the fringes. For many, it holds sad memories. It’s hard for them to come back.

For me, coming back and facing those memories puts me in the driver’s seat of my own emotions. It heals us all to have young fellas like Jeremy listening and understanding his mother’s pain.

Honouring memory

Jeremy, who is Elsie’s son, explains that when you meet other Noongars they ask about your background – where you’re from, your Country, who your mob is.

For a long time I didn’t quite know. That was part of Mum being taken away. I want to learn from Elders while they’re still around, and hopefully pass that to my kids when they’re older. To hear ‘that’s where your grandmother used to camp’ is amazing. I’d like to spend time here to learn how they lived, and recapture part of that feeling.

Eugene sums up this Boodja-family connection:

it’s not just about burning, weeding, replanting. It’s about demonstrating our deep love and care for our old people through these actions. They did their very best for us and our kids, even when denied the opportunity.

We want to keep coming back as families, listening, learning, having a feed, practising culture here again.

For Eliza, it’s important to come back and honour her mother’s memory.

This is her Country so looking after it feels like we’re looking after our mum and our grandparents.

I’ve got a photo of Mum, me and my little sister sitting there [pointing to a big morrell tree]. And the mangaart, they were nice shady trees, they’re wanyarn [sick] now. We can clean up and rejuvenate them with fire.

And that’s what intergenerational and Elder-led restoration is. It’s about rebuilding love and family connections, because they’re still here under all these weeds.

It’s also what the Walking Together project is about. Elders, their families and scientists collaboratively learning to look after and restore important places. The project focuses on Elders’ connection to Country, sharing and recording stories, giving comfort that their knowledge won’t disappear with their passing.

It’s for the next generation who will one day be Elders to learn heritage and cultural skills. And it’s for conservation scientists and practitioners to learn about the deep human history of landscapes and ecosystems they work among, helping us all to understand Country and connect a little deeper.

Alison works on the Walking Together project, which is delivered by UWA in partnership with South Coast NRM and supported financially by Lotterywest. A second project she works on is funded by an ARC Discovery Indigenous grant.

Eugene Eades works on the Nowanup Caretakers of Country project which is financially supported by Lotterywest.

Eliza Woods, Elsie Penny, and Jeremy Lacco do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.