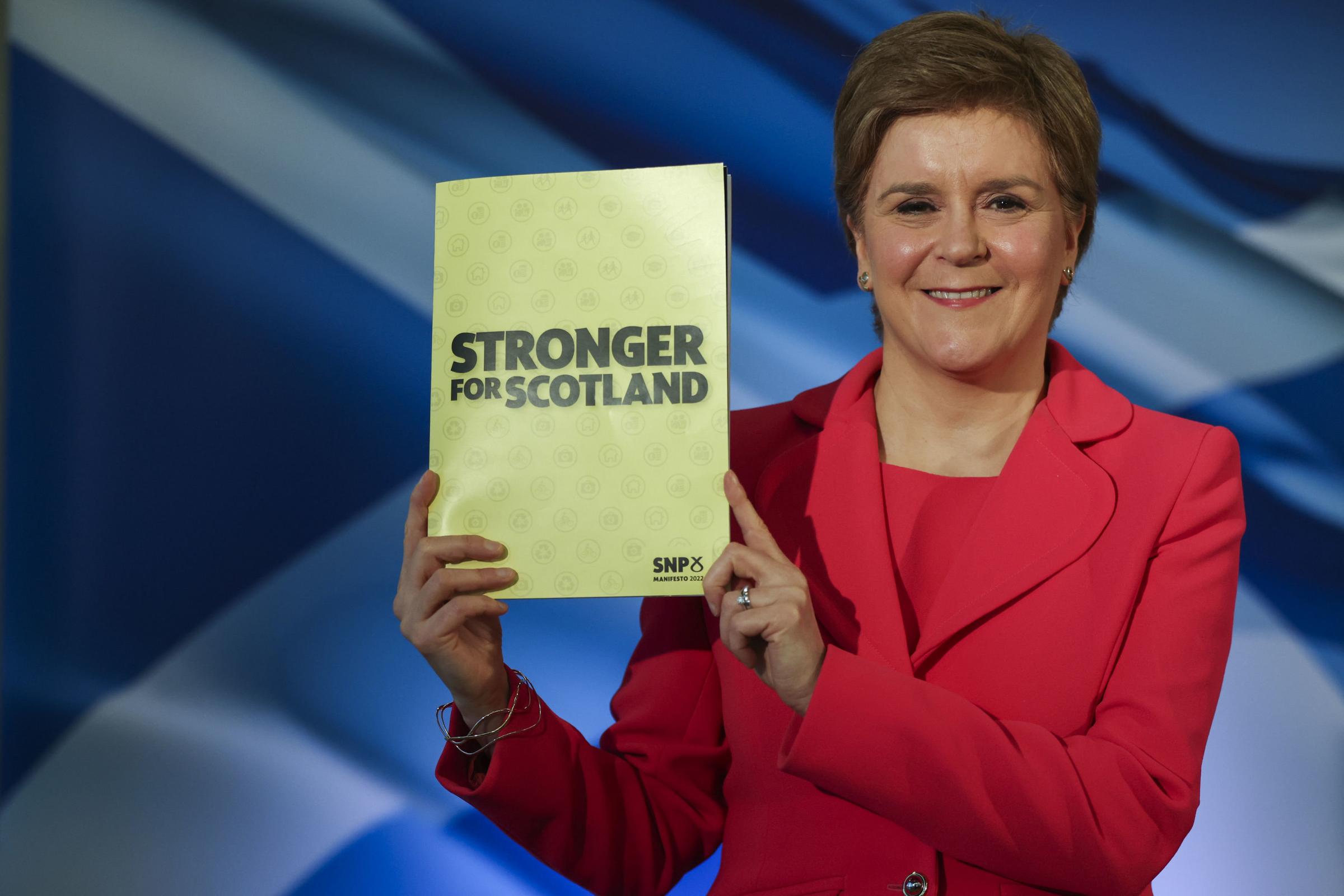

SCOTS are poised to head to the polls in what First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has dubbed “the most important local elections in the history of devolution”.

The SNP are aiming to maintain their status as the country’s dominant political force, while the pro-independence Greens are also hoping to build on their record-breaking results in the 2021 Holyrood ballot.

The Tories overtook Labour in the 2017 local elections, with the two parties vying for second-place overall this time around. The LibDems, meanwhile, are looking to halt their recent electoral slide.

To get a sense of where the five largest parties are placed heading into the May 5 ballot, The Sunday National spoke to three leading polling experts – Mark McGeoghegan (MM), James Kelly (JK) and Mark Diffley (MD).

SNP

What's changed since 2017?

MM: In a sense, the SNP are now back where they started, once again hoping that a solid local election result will provide a solid platform on which to press for a referendum, and perhaps even to hold a referendum and to win it. As in 2017, though, they are trying to build that platform with a campaign that mostly avoids the topic of independence, which may not be the most promising way of motivating passionate independence supporters to turn out to vote.

JK: Both the 2012 and 2017 local elections were fought against disadvantageous political backgrounds for the SNP. In both sets of local elections, the SNP won 32.3% of first preferences, significantly below their Holyrood results. This time, Brexit is no longer an issue that could sap the party’s support, and they have long since successfully built broad support among the larger pool of post-2014 pro-independence voters.

MD: The party remains the pre-eminent political force in Scotland. Recent polling suggests that the SNP will not only come first in these elections but may surpass their best performance at local ballots. The First Minister remains the most popular party leader, though support for independence has declined marginally in recent months.

What's their main selling point?

MM: Independence remains the bedrock of the SNP’s offer, even in local elections and even if the words “independence” and “referendum” are consciously excluded from candidates’ vocabularies.

JK: The campaign pitch is essentially that electors should use a vote for the SNP to “send a message to the Tories” that they want to “ease the squeeze”. That’s a rather convoluted concept, and the SNP will have to hope that voters at least hang around long enough to take on board the explanation of what the nebulous slogan “ease the squeeze” is intended to mean, ie tackling the cost of living crisis.

MD: More effective action to tackle the cost of living crisis. Push for a second referendum (among the party’s voters).

Best/worst case scenario

MM: A recent Ballot Box Scotland poll put the SNP on 44% of first preferences, but that seems unrealistically high. Nevertheless, breaking the 40% barrier would be an absolute best-case scenario for the SNP, and could come with around 50 additional councillors. Any backsliding at all would be a bad result. Labour have been enjoying a recent resurgence in the polls and will be coming for the urban centres lost in 2017. Losing Glasgow, for example, would be a serious blow.

JK: The SNP’s best opinion poll showing for the first-preference vote remains the 45% recorded in a Panelbase poll that I commissioned last autumn. A more recent poll by Survation had them at 44%. That sort of result would be an all-time high but few commentators truly believe it will be replicated on polling day. Another result along the same lines as 2017 certainly can’t be ruled out, and arguably something slightly poorer would constitute the true worst-case scenario.

MD: The best-case scenario is a record first-preference vote share and taking Glasgow/Edinburgh/Dundee as a majority. The worst is not improving on 2017 and losing minority/joint control – especially in Glasgow, Edinburgh or Dundee.

Prediction

MM: The SNP historically underperform their Holyrood polling in local elections, and based on that pattern, winning 33% to 37% of first preferences seems reasonable.

JK: I suspect the SNP will make some progress, both in terms of votes and councillors. It remains to be seen if the gains will be sufficient to wow the mainstream media, and I would be surprised if the 40% barrier is broken in the popular vote.

MD: I predict the SNP will be the largest party, with the most councillors, a first-preference vote share of around 40%, and with no overall majority in Glasgow, Edinburgh or Dundee.

CONSERVATIVES

What's changed since 2017?

MM: The Conservatives have lost Ruth Davidson and replaced her with a very unpopular Douglas Ross, and have lost their main selling point to right-leaning and Leave-supporting voters – Brexit. Unlike in 2017, the party is also mired in scandal and is seen to be failing to address the cost of living crisis.

JK: The Scottish Tories are in a markedly weaker position than they were five years ago, when Ruth Davidson was at the peak of her powers. The opinion poll evidence is clear – the public do not rate Douglas Ross at all. And, of course, an even bigger drag on their support is the public’s disdain for Boris Johnson’s administration in London.

MD: 2017 was a high-water mark for the Scottish Conservatives. Recent polling suggests that support has slipped to below 20%, making Labour favourites to come second this time round. This mirrors UK-wide polling which has seen support drop in the wake of law-breaking during Covid lockdowns.

What's their main selling point?

MM: Unionism remains the Conservatives’ political strength, but there are other Unionist parties with fewer politically toxic problems. Many of those who voted Conservative in the past few elections could decide that enough is enough, and switch to Labour or the LibDems to send a message.

JK: You have to pinch yourself to believe it, but the Tories do not appear to be primarily running on a “Say No to Indyref2” message in these elections. Instead, the main pitch is “we’ll focus on your local priorities, not the SNP’s”.

MD: Consistency on the constitutional message, standing up to the SNP.

Best/worst case scenario

MM: The best case for the Conservatives really is just holding on to their 2017 position, which looks highly unlikely given current polling. A collapse to their 2012 position – 13.3% of first preferences – is unlikely to happen, but could if Labour perform well in the central belt and the SNP make gains in the north-east and south.

JK: The best-case scenario would probably see some slippage from the 25% of the first-preference vote they took last time, and at least some modest seat losses. The worst-case result might see them slip perilously close to their 2012 result.

MD: The best-case scenario is retaining second place and control in councils where they share power or have minority control. The worst-case scenario is coming third behind Labour and losing control in councils where they share power or have minority control.

Prediction

MM: The Conservatives tend to perform in local elections roughly in line with their Holyrood polling, which would indicate 16% to 19% of first preferences and potentially substantial losses.

JK: The most likely outcome for the Tories is rough equidistance between their 2012 and 2017 results, which would see them lose dozens of seats, probably translating into a reduction in the number of councils they jointly control.

MD: Third place.

LABOUR

What's changed since 2017?

MM: The party is in its strongest polling position in around seven years and has the most popular party leader in Scotland, bar the First Minister.

JK: The UK and Scottish Labour leaderships are both harmoniously leaning rightwards, and the party’s polling position in the campaign period is somewhat improved.

MD: Under its new leader Anas Sarwar, the party’s polling has improved marginally, largely at the expense of the Conservatives.

What's their main selling point?

MM: Labour’s best national pitch at this election is as an option for voters looking to give a kicking to either – or both – the parties of government at Holyrood and Westminster.

JK: Labour are clearly still seeking the Unionist route to success by relentlessly portraying themselves as the party best placed to beat the SNP.

MD: There is a new leader and unity between the UK and Scottish parties, and the party is an alternative for Tory voters dissatisfied with the Prime Minister.

Best/worst case scenario

MM: If both of their best national pitches come off, Labour could win around 26% to 27% of first preferences, regaining around half of the 133 councillors they lost in 2017. Labour’s worst-case scenario is tied to the SNP’s best case, with Labour pushed out of any representation in wards across the central belt JK: It’s conceivable that Labour could make really telling gains in their former heartland areas. Although it seems unlikely that Labour will do worse than five years ago, modest losses are possible.

MD: Labour’s best-case scenario is claiming second in terms of first-preference votes and number of councillors, and winning overall majorities in any councils where they are currently a minority administration, such as Inverclyde or North Lanarkshire. Their worst case is remaining in third place and making no progress.

Prediction

MM: Labour historically outperform their Holyrood polling in local elections, and that polling positions them to replace the Conservatives as Scotland’s second party. They’re likely to win 22% to 26% of first preferences.

JK: My suspicion is that Labour will make at least minor gains, but will share any spoils with the SNP. That means they may not be able to establish a narrative that they are the clear “winners”.

MD: I would predict Labour in second ahead of the Conservatives, with no overall majorities in any council.

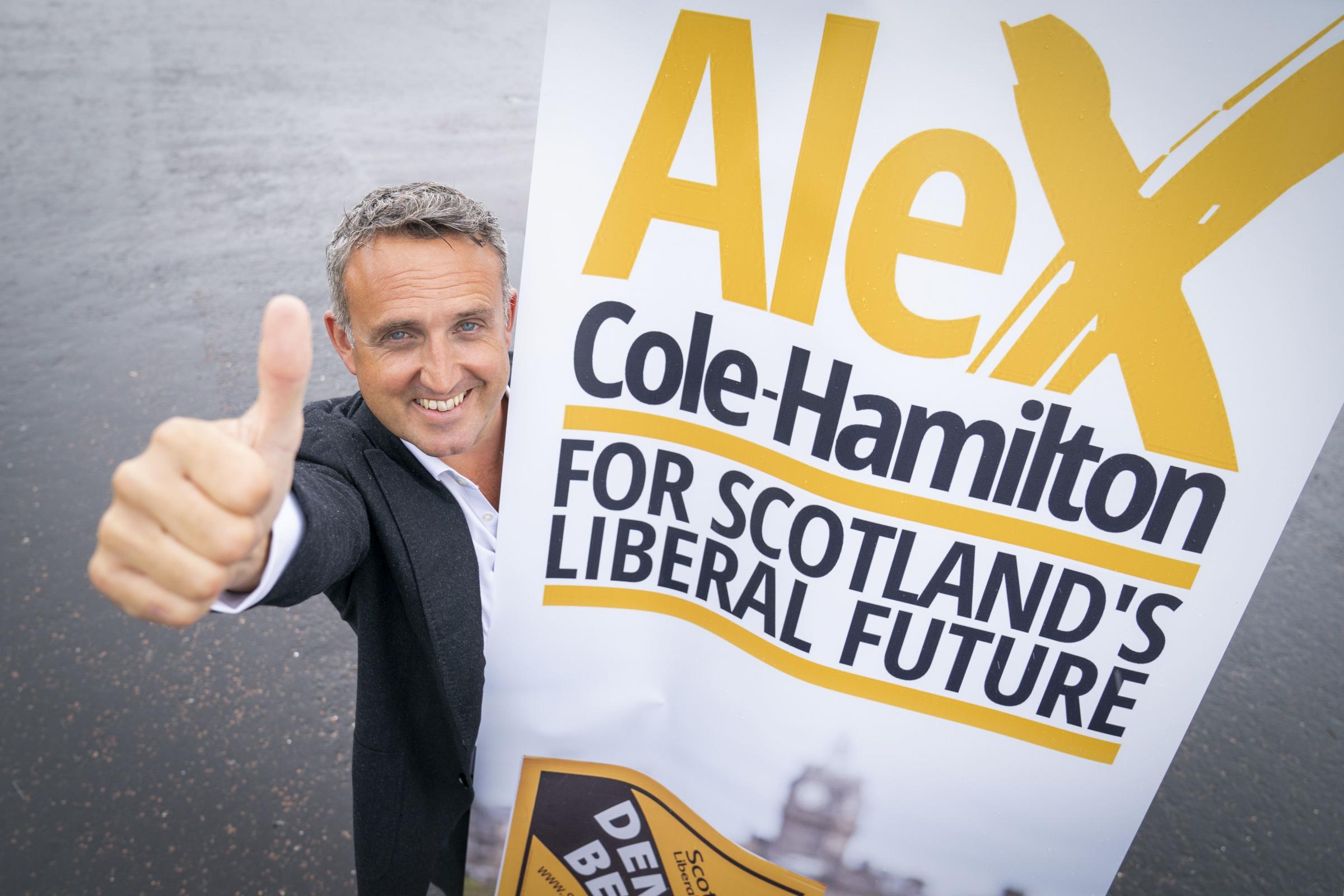

LIBDEMS

What's changed since 2017?

MM: Since 2017, the LibDems have largely continued a trend of collapse that began in 2011.

JK: They’ve transitioned from being a pro-EU party to one which tacitly accepts Brexit as a price worth paying for remaining in the UK. Willie Rennie has been replaced as leader by Alex Cole-Hamilton, a process that Cole-Hamilton characterised himself with typical modesty as akin to the West Indies moving from endearing-but-ineffective “Calypso cricket” to world-beating “fast bowling”. There’s absolutely no evidence in the opinion polls that the LibDems have succeeded in moving into a higher league, but we mustn’t exclude the very real possibility that it still looks like that inside Mr Cole-Hamilton’s own mind.

MD: The party fell from fourth to fifth place at last year’s Holyrood election, winning just four seats.

What's their main selling point?

MM: They don’t have much of a selling point nationally, but where they spend resources they can present an appealing, local alternative to the main parties.

JK: The LibDems’ usual tactic in recent years has been to focus almost entirely on very specific geographical areas where they can plausibly convince supporters of other Unionist parties that only LibDem votes can keep the SNP out. That approach doesn’t work so well in multi-member wards with a preferential voting system.

MD: They promote more local decision-making and offer a solid second preference for Labour and Conservative voters.

Best/worst case scenario

MM: Making any gains at all would be a good result. In the worst-case scenario, they fail to make gains in Fife, Edinburgh and Highland, and lose seats in Aberdeenshire.

JK: The difference between the best-case and worst-case scenarios is probably smaller for the LibDems than it is for any other party. It’s very hard to imagine them getting more than around 8% or 9% of the vote, and therefore the best they can hope for is relatively minor seat gains.

MD: The best-case scenario is coming fourth in terms of first-preference votes and increasing the number of councils where they share control (currently six). The worst-case scenario is finishing behind the Greens and losing influence in one or more councils.

Prediction

MM: Typically, the LibDems slightly outperform their Holyrood polling in local elections, which would put them on course for 7% to 9% of first preferences. It should be enough to make a few gains.

JK: The most likely scenario is that the LibDems remain fairly static in terms of seats.

MD: I predict fourth place in terms of councillors elected. They need to rely on second-preference votes.

GREENS

What's changed since 2017?

MM: The Greens have slowly broadened their support since 2017. They’ll be looking to build on those gains.

JK: There are Green ministers for the first time anywhere in the UK. So far, there’s been no sign of a Green dip in the polls, and the party’s ambitions in these elections seem higher than ever.

MD: The big change for the Scottish Greens was their breakthrough at the 2021 Holyrood election, claiming fourth place and winning seven seats.

What's their main selling point?

MM: As a pro-independence, left-wing party whose core issue has been climbing up the political agenda in recent years, they have a solid pitch to a significant chunk of Scottish voters who will consider some combination of SNP and Green first and second preferences.

JK: The Greens can speak with more authority and credibility on the climate emergency than other parties, and they’ve also positioned themselves as the purest of the pure on identity politics issues.

MD: Their main selling points are local action to solve global problems on the climate and pushing for a second referendum (for their voters).

Best/worst case scenario

MM: The best-case scenario for the Greens would be to make further gains on their Holyrood regional vote share last year, which would trigger breakthroughs across parts of Scotland in which they have no current representation at a local level. Going backwards at all would be a disappointing result given their gains at Holyrood last year.

JK: The Greens are standing in the majority of wards, can probably expect transfers from large numbers of SNP voters and have been as high as 14% in recent Holyrood list polling. That looks like a potential recipe for very substantial progress. However, it’s possible they could end up with a result that isn’t significantly better than five years ago, especially if SNP voters are foolish enough to heed their party’s wishes about not ranking other pro-independence parties.

MD: The best scenario is improving first-preference vote share and the number of councillors from 2017 and achieving joint control of at least one council. The worst scenario is finishing behind the LibDems and losing councillors.

Prediction

MM: The Greens typically slightly underperform their Holyrood polling in local elections, which would set them up to win 6% to 8% of first preferences. Converting that into seats will be difficult, but should mean they make gains outwith Edinburgh and Glasgow (which accounted for 15 of their 19 seats in 2017).

JK: The Greens look extremely well placed for a record result and may move a little closer towards ending one of the remaining vestiges of Scotland’s former four-party system.

MD: I predict the Greens as fifth in terms of councillors, with joint control achieved in at least one council.