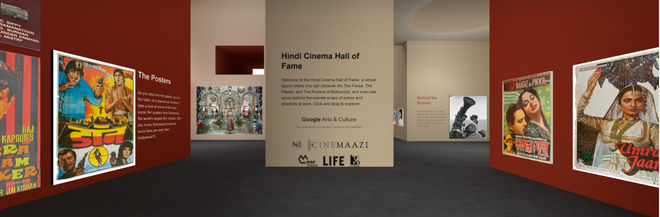

One of the categories within Google Arts & Culture’s (GAC) latest exhibition on Hindi film history is titled Pocket Gallery — a name that brings to mind memories of those treasured childhood collections, the troves of matchbox covers and film posters carefully stowed away. It opens into a virtual space that imitates an art gallery, complete with floors, rooms, and walls, which the user can navigate using their keypad. On a wall hangs a black and white photograph of filmmaker V. Shantaram poring over a strip of film, engrossed in editing at the erstwhile Prabhat Studios, his face softly illuminated by a beam of light. In the next hall, a horde of portraits — in monochromes and in colour, spanning different eras — are bunched together. The design is fascinating and fun but also radical, for it brings a vast collection of cultural treasures from brick-and-mortar vaults to an immensely accessible ‘museum without walls’.

Unveiled on November 20 at the opening ceremony of NFDC Film Bazaar in Panjim, the exhibition marks GAC’s foray into the world of Indian cinema. Collaborating with 21 cultural organisations such as the National Film Archive of India, the Museum of Art & Photography, Cinemaazi, and Bollywood studio giant Yash Raj Films, it presents a multifaceted narrative of Hindi film history (now available on the GAC website.) There is an abundance of film ephemera — over 7,000 high-resolution behind-the-scenes stills, posters, and videos — whose weight is offset by over 120 meticulously curated stories. A collection of stills accompanied by vividly descriptive notes, curated by documentary filmmaker and author Nasreen Munni Kabeer, delves into Hindi cinema’s Golden Era (the late 1940s to the early 1960s), while one of the sections curated by the Museum of Art and Photography narrativises the portrayal of female friendships.

Particularly striking is how the exhibition demonstrates technology’s potent role in bridging individuals with archival materials. The user can browse movie posters from over 100 years, neatly sorted by their colour palettes, and photographs arranged in a chronological timeline. Using Google’s Augmented Reality and Street View technologies, the platform arranges a virtual tour of Mumbai’s grand old cinema halls — Liberty, Regal, and Eros — and film studios, capturing their architectural splendour through immersive 360-degree imagery.

Amit Sood, the head of GAC, joining the conversation virtually from London, refrains from calling the platform a museum or an archive. “I think of it as an online resource that gives people incredible access to cultural information from across the globe,” he says. “It is a place where people can come to feel inspired and have fun without being intimidated by high culture. We have around 3,000 cultural partners from 80 countries, all consolidated onto a single platform. It is about fostering inspirational and playful interactive experiences, all built upon a robust foundation of expertly curated archival storytelling.”

Does digitisation of museum collections present a challenge to brick-and-mortar museums by discouraging physical visits?

Online platforms can give you a taste of what, say, the Museum of Modern Art [MOMA] has to offer. But they can never fully replace the experience of physically visiting a museum. It is true that now you can get some tactile experience online — mobile phones are the most common tactile interface — and we are also exploring augmented reality [AR] projects, allowing for immersive experiences in living rooms or classrooms. However, the notion of going into a museum can never be replicated online. We are not here to replace museums; we are a team of engineers and technologists. Museums do the critical work of research and curation, and we build accessibility and democratisation of these works. We have managed to work with the cultural ecosystem for so long because it is never a question of ‘either-or’; our goal is to supplement and complement existing frameworks

How long have you been working on Hindi cinema project?

Apart from the fact that Indian cinema is vast and has great commercial value, its film archives possess an immense storytelling quality. That is what we wanted to tap into. My first meeting was with film critic Anupama Chopra, around three-four years ago, and then we began conversations with the National Film Archive of India. Slowly, we got in touch with private archives like Cinemaazi, Shemaroo, Ultra, and Yash Raj.

What are the fundamental policies concerning acquisition, curation, and exhibition?

The primary policy is that the partner must own the content legally; we get the digital rights to put them up on the platform as a non-commercial entity. Curatorial policies remain with the partner, too. We ask for generic themes like education, nostalgia, and inspiration, but the stories are designed by the partner. This approach is what makes our content highly diverse. For instance, it was when a partner gave us exceptional content on Sivaji Ganesan and M.G. Ramachandran that we recognised the need for Phase 2. Now, we are working with more partners and expanding our platform beyond Hindi cinema.

In a society like India’s where awareness about archiving is still at an early stage, what challenges do you face?

The fragmented nature of archiving in India is both a challenge and an opportunity. Many individuals are private collectors and tracing them is not easy. But it ensures that there is no single authority defining Indian film history. You get many viewpoints. A lot of content we have is from these private parties. The unique challenge we face in India is in establishing trust and nurturing long-term relationships with private archives, particularly the smaller ones. For instance, when pursuing access to [actor] Nutan’s family albums, they sought assurances regarding preservation methods. Our partners feel reassured knowing that we operate on a non-commercial basis and the rights always remain with them.

I think now more and more people are realising that digitisation is not just nice to have, but also critical from a preservation standpoint because there is always the risk of losing the collections in brick-and-mortar archives to man-made or natural disasters. Salarjung Museum in Hyderabad, for instance, did not have a lot of online content until a few years ago, but now they are one of the most prolific publishers on GAC. They do the archiving, digitising and storytelling all by themselves.

What are GAC’s future plans in India?

For a country like India, where there is a constant need for cultural storytelling, a finishing line does not exist. Now people see GAC as a treasure trove of content, but I feel it is incomplete in so many ways. Our first step would be to open the platform up for more partners, to get more stories. I would love to have Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, and other regional cinemas represented here. In the next four to five years, I see our Indian cinema section evolving into one of the most regionally diverse ones on the subject.

The writer is a film critic currently residing in London.