VULNERABLE kids are paying the price of a broken child protection system, says NSW Minister for Families and Communities Kate Washington, because the system has been left to "spiral out of control".

The solutions aren't simple and it will take time to turn around but the status quo was "unacceptable".

"The Minns Labor Government has inherited a broken child protection system where vulnerable kids are paying the price," Ms Washington said.

"We cannot accept kids being holed up in motel rooms and going hungry whilst millions of dollars are being paid to providers. We are making necessary decisions to repair the budget to rebuild essential services like child protection.

"Coming into government, we knew there was a lot of difficult work to do to fix the broken child protection system, and we are getting on with the job."

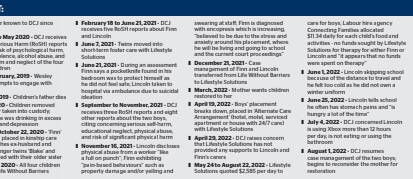

Her comments follow a review into system-wide failures highlighted by the case of two boys, dubbed 'Finn' and 'Lincoln', removed from their mother's care in 2020 which has become the focus of reform after Children's Court magistrate Tracy Sheedy put their story on the public record.

In a judgement handed down in October, Ms Sheedy detailed what she described as the children's "unconscionable" treatment and "appalling neglect" since coming into out-of-home care.

In response, the Department of Communities and Justice put former National Children's Commissioner for the Australian Human Rights Commission Megan Mitchell in charge of a review. In her report, made public on Thursday, every one of the service providers paid to care for the children was found lacking.

They included Lifestyle Solutions and Life Without Barriers which both started out as small, family-led organisations in Newcastle, as well as the Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ).

Lifestyle Solutions sought $2585 per day to care for the boys, while the labour hire agency subcontracted to deliver their day-to-day care, Connecting Families, say they were allocated just $11.34 per day for each child's food and activities.

In a media statement, Lifestyle Solutions acknowledged the 24 recommendations made in the Mitchell review.

"We accept that the care provided to the children in this matter did not meet the expectations of the community or acceptable standards."

It provided no information about the boys' funding, what changes it had since made, or give any reasons about how the boys were so neglected for so long while in their care.

"As a human rights based, not-for-profit service provider, we strive to deliver services that create safety and empowerment for children and young people," the statement said.

"We acknowledge the review's finding of the systemic and complex challenges facing out-of-home care, particularly around workforce skills shortages, the dearth of foster carers and the lack of suitable housing for children in the out-of-home care system. We continue to address these issues in our services and in collaboration with the sector."

For its part, Life Without Barriers said it had reviewed the Mitchell report and supported its findings and recommendations.

"Upon receiving the report, we commenced immediate work to imbed the relevant improvements to our services and we will continue to explore all opportunities to consistently enhance the services we provide," the statement said.

"We thank the Department of Communities and Justice for the opportunity to participate in the review and we will continue to work in partnership with children and young people and the Government to deliver safe and quality services across NSW.

After being removed from their mother's care, six months after their father died, the boys were the subject of eight Risk of Serious Harm (RoSH) reports concerning serious self-harm, educational neglect, physical abuse, and risk of significant physical harm.

Complaints involved workers screaming and swearing at the boys, smoking in the house, allowing them to play Xbox up to 12 hours per day without eating or using the bathroom, physical abuse, and school refusal.

The school principal reported never knowing where the children were or who was supposed to be picking them up. One of the boys complained of stomach pains because he didn't get enough to eat, and said he sometimes didn't attend school because he was too cold, with no winter uniform.

For weeks at a time, Lifestyle Solutions failed to respond to the department's request for information, including a lack of therapeutic support for the boys, or contact with their other siblings.

There are 18,000 children in crisis in the Hunter Central Coast region, and less than one in five have had contact with a caseworker, according to the most recent statistics, as the number of frontline workers employed to protect them continues to decline.

The other 14,817 children identified as being at risk of significant harm, have been left to fend for themselves.

Ms Washington said the review's findings firmed her government's resolve to drive "significant reform of the sector, for the sake of vulnerable families and children across the state."