Evidence continues to assemble that Venus is more geologically active than previously thought.

Planetary scientists scouring decades-old data from NASA's Magellan spacecraft have found signs of lava flows coming from two volcanoes on Venus that erupted in the early 1990s. That was when Magellan orbited the hellish world overhead.

This marks the second time scientists have identified direct geological evidence of recent volcanic activity on Venus, suggesting the planet could be as geologically active as Earth, with volcanoes possibly spewing on its surface as you read this.

Related: Venus volcanoes may be powered by long-ago violent impacts

Venus and Earth are nearly the same size and were showered with equal amounts of water billions of years ago. For this reason, many scientists wonder why Venus turned into a hellscape while our planet bloomed into a habitable orb. Studying Venus' volcanic activity, which scientists suspect is driven by internal heat, may offer a window into the evolution of both planets.

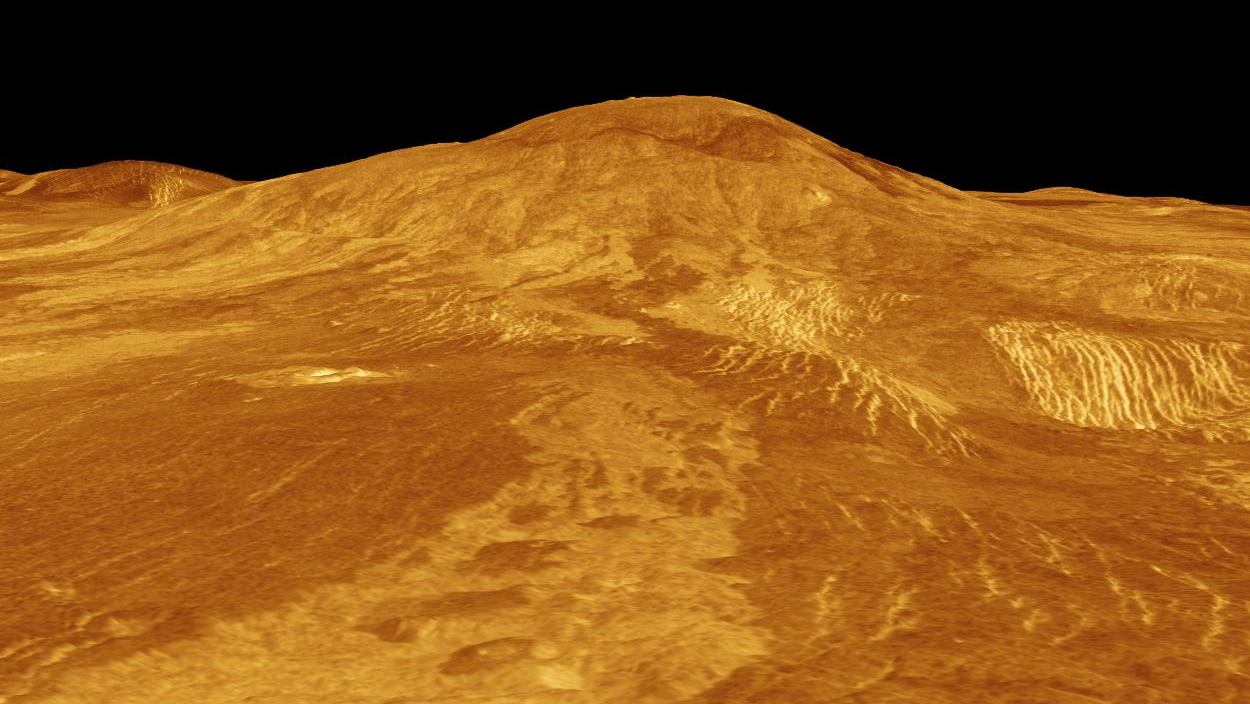

The newly spotted lava flows appear to have oozed out from the western slopes of Sif Mons, a huge shield volcano, and Niobe Planitia, a relatively flat region home to many volcanoes. By referencing lava flows on Earth, scientists estimate Sif Mons' eruption poured about 12 square miles (30 square kilometers) of rock, which is sufficient to fill 36,000 Olympic swimming pools. The Niobe Planitia eruption blasted lava that could fill 54,000 Olympic pools, NASA said in a statement. To put that into context, however, the 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa in Hawaii — Earth's largest active volcano — spouted enough lava to fill 100,000 Olympic pools.

Evidence for the newfound lava flows is rooted in radio waves beamed at Venus via Magellan's radar. These waves zipped through the planet's thick, toxic clouds before bouncing off the world's surface and returning back to the spacecraft. These reflections, known as backscatter, can ferry information about a planet's rocky surface.

While analyzing Magellan's data gathered between 1990 and 1992, scientists found the signal strength had increased during later orbits. They interpret the spike as bright, freshly formed rocks on the surface — which are likely solidified lava.

"We interpret these signals as flows along slopes or volcanic plains that can deviate around obstacles such as shield volcanoes like a fluid," study co-author Marco Mastrogiuseppe of Sapienza University of Rome said in a statement. "After ruling out other possibilities, we confirmed our best interpretation is that these are new lava flows."

The newly identified lava flows appear bright in radar data, which could mean they are young and thus not yet eroded. Alternatively, these results could also mean the lava is rougher than its older, smoother surroundings, study lead author Davide Sulcanese of the Università d'Annunzio in Pescara in Italy told Sky & Telescope.

The findings build on last year's historic discovery of an altered vent of the volcano Maat Mons near Venus' equator, which appeared to have changed shape and grown noticeably larger over eight months, likely due to an eruption-triggered collapse.

"This exciting work provides another example of volcanic change on Venus from new lava flows that augments the vent change Dr. Robert Herrick and I reported last year," study co-author Scott Hensley, a senior research scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a statement. "This result, in tandem with the earlier discovery of present-day geologic activity, increases the excitement in the planetary science community for future missions to Venus."

This research is described in a paper published Monday (May 27) in the journal Nature Astronomy.