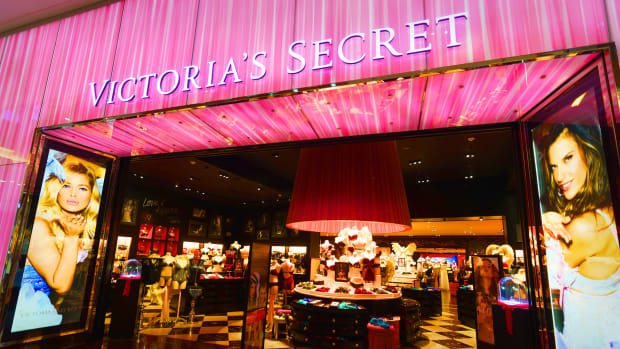

When I was a teenager, there was only one major store in the average mall to buy "nicer" bras and underwear from, and that store was Victoria's Secret (VSCO).

From its pink-striped walls to its generous assortment of ultra-slender mannequins modeling all varieties of undergarments that barely covered their bits properly, it may have seemed to the average browser that Victoria's Secret sold lingerie.

But what it really sold was the fantasy that women could buy things there that magically transformed them into the ideal vision of a woman as curated by the male gaze: big hair, big breasts, tiny waist, and legs that easily seem twice of the length of any average woman's.

Image source: Shutterstock

Misogyny Inside Victoria's Secret

Those familiar with the company's history know that it has been historically resistant to diversity. The Victoria's Secret Fashion Show, which ran from 1995 to 2018 and was watched by millions at its peak, primarily featured tall, thin white women and was repeatedly called out for objectification, lack of diversity, and cultural appropriation.

In 2021, The New York Times published an investigation called "Angels in Hell: The Culture of Misogyny Inside Victoria's Secret," which revealed just how bad things inside the company really were, calling it "an entrenched culture of misogyny, bullying and harassment."

Leslie Wezner and Ed Razek, the two executives behind Victoria's Secret parent company L Brand (LB), were both brought into the spotlight for bad behavior. Wezner was revealed to have connections with Jeffrey Epstein and Razek was accused of sexual harassment. Both have since left the company.

Today, Victoria's Secret is trying to leave those days behind. It's made big strides to change its image, from more plus-size models to launching the VS&CO Essentials program, which partners with nonprofits such as I Support The Girls to provide underwear to women in need.

But I still won't shop there.

Performative Inclusion

I stopped going to Victoria's Secret many years ago, long before Razek trumpeted publicly that the brand was only for thin women. I still found their products pretty, but often not particularly functional -- which is a major signifier of clothing made by men, especially lingerie.

The reason I stopped buying from Victoria's Secret wasn't so much about the bad press it got -- although I was glad I had moved away from shopping there when I did see it -- but because I discovered lingerie brands founded by women that offered beautiful, comfortable products, such as Harper Wilde and True & Co.

Not only that, but the models on all sections of those brands' websites are of all colors and sizes. Some of them had stretch marks, underarm hair, big thighs -- they were lovely, and they just looked like people, rather than extremely glamorized women trying to look at sexy as possible.

Even better, the brands joyfully celebrated those things, leaving me to feel like maybe it was okay to have those features myself, instead of staring at Victoria's Secret models and feeling somehow less than for being a size 14.

While the models that represent Victoria's Secret today are more diverse (especially in its social media presence), the brand still has a lot of work to do. Clicking into verticals on the Victoria's Secret website today still leads to a ton of models that have the old Victoria's Secret look, which makes the company's efforts feel like performative inclusion to me.

Since the rise of the body positivity movement over a decade ago, people have been demanding to see "more people who look like them." And it's having an impact when they do. From Target's (TGT) efforts to mix plus-sized mannequins in with regular ones to Old Navy's (GPS )push to offer sizes 0-30 in all its stores (which has hit some snags, but still), today's consumer wants something very different than they did a decade ago. And for this consumer, Victoria's Secret is just a bit too late to adapt for my personal tastes.