Currently, the planet Venus is visible, albeit very low in the west-northwest evening sky right after sundown. Those with obstructions such as trees or buildings toward the west may not be able to see Venus yet thanks to its very low altitude. But this current evening apparition of Venus is going to evolve into a very good one in the coming days and weeks, so let's get into a fuller explanation as to what is to come.

Venus passed superior conjunction (appearing to go directly behind the sun as seen from Earth) back on June 4. Initially, it was mired deep in the brilliant glare of the sun. Nonetheless, in the days that followed it moved on a steady — albeit very slow — course toward the east and gradually pulled away from the sun's vicinity.

And now, as we are about to make the transition from July into August, Venus has finally begun climbing up out of the sunset glow in earnest and is now about to reclaim its role as the brilliant Evening Star, a title it has not held since roughly a year ago. Look for it now by scanning with binoculars shortly after sundown very low in the western sky. Venus will stand about 9 degrees high in the western sky at sundown (your clinched fist held at arm's length is roughly 10 degrees wide) and will touch the horizon about 50 minutes after sunset, giving less experienced sky watchers a chance to get a good glimpse.

Want to see Venus in the night sky? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

During August, Venus sets around the middle of twilight; find it with binoculars right after sunset and with the naked eye some 20 to 30 minutes later depending on sky conditions and local topography. It gradually creeps a little higher as the month progresses; by the end of the month, you can try seeking out Venus 30 or 40 minutes after sundown.

With binoculars and a clear sky on Aug. 4, you may be able to spot tiny Regulus — the brightest star in the constellation Leo the Lion — slightly more than 1 degree to Venus's lower left. The following night Regulus is about 1 and a half degrees below Venus. But there's also a bonus that same night as well.

Sitting just three-quarters of a degree to the upper right of Venus will be an ultrathin waxing crescent moon, just 36 hours past new phase and only 2 percent illuminated. You'll likely need binoculars, and Venus might have to guide you to the extremely thin lunar crescent's location, for Venus at magnitude -3.9, may be an easier body to spot than the moon.

Brilliant winter holiday beacon

Venus should become a bit easier to see during September. By Oct. 1, it will set about 30-degrees south of due west nearly 75 minutes after sunset. Continuing to swing east of the sun as the fall season progresses, Venus will become plainly visible in the southwestern evening sky even to the most casual of observers by Thanksgiving.

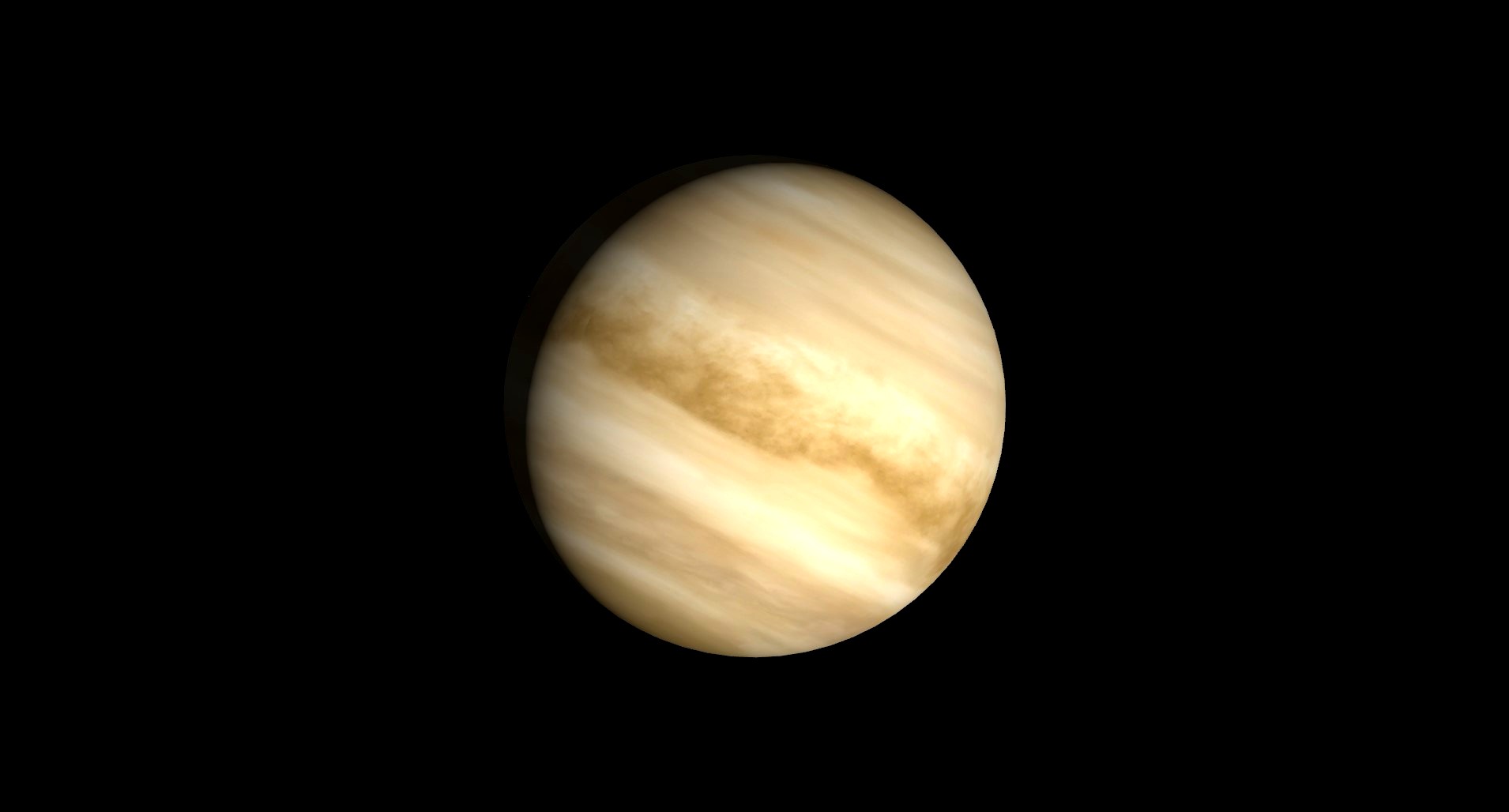

Appearing as a brilliant silvery-white star-like object of magnitude –4.3, our sister planet will set almost four hours after the sun by Christmas Day. In fact, if the air is very clear and the sky a clean, deep blue, you might try looking for Venus shortly before sunset. As the sky darkens, it will seem to swell from a tiny white spark to a big, almost dazzling Christmas-season star.

The Venus Show

It will be during the winter of 2025 that Venus will perform like a sequined showgirl, calling attention to herself each evening. Viewed in the western twilight, this planet always appears dazzlingly bright to the unaided eye, and more so in binoculars. Venus reaches its greatest elongation — its greatest angular distance — 47 degrees to the east of the sun on Jan. 10.

It will appear at its brightest in mid-winter as it heads back down toward the sun, reaching its greatest brilliancy for this apparition on Valentine's Day (Feb. 14) at magnitude –4.8. The planet will be most striking then; shining more than twice as bright as it does now.

Venus will then slide back toward the glare of the sun, but because it will appear to pass more than eight degrees north of it when it passes inferior conjunction on March 22, a most unusual circumstance will take place for a few days around that time: Venus will be visible as both an evening and morning object, glowing low in the west right after sunset and also low in the east just before sunrise. It finally (almost reluctantly) will vanish for evening viewers by the end of March.

Phased out!

Between now and the end of March, repeated observation of Venus with a small telescope will show nearly a complete range of its phases and disk sizes. Currently, the planet appears almost full (it was 97-percent sunlit on July 27), and through the first half of the upcoming fall season will display nothing more than a tiny, dazzling gibbous disk. It will start becoming noticeably less gibbous by early December.

On Jan. 11, 2025, Venus reaches dichotomy (displaying a "half-moon" shape). Then, during February, it shows us an increasingly large crescent phase as it swings toward Earth. Indeed, those using telescopes will note that while the Earth-Venus distance is lessening, the apparent size of Venus' disk will grow, doubling from its present size by the first night of winter (Dec. 21). When it has doubled again in size on Feb. 16, its large crescent shape should be easily discernable even in steadily held 7-power binoculars.

But even after it passes through inferior conjunction on March 22, our Venus show will be not yet over, for it will dramatically reappear as a dazzling "morning star" low in the eastern sky at the beginning of April. Then, a repeat performance will begin, with the evening sequence of events happening in reverse, continuing right to the end of 2025.

Want to get an up close look at the planets of the night sky? Be sure to take a look at our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars.

And if you want to photograph Venus or any other planets, we have tips for how to photograph the planets, as well as guides to the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.