Some time in the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, 17-year-old Kristina Ross became “one of the youngest actors ever selected” to enrol in the Drama School of the Victorian College of the Arts. Her experiences so shaped, reshaped, made and unmade her that many years later she reconfigured them as fiction.

The resulting novel, First Year, has been awarded the Australian/Vogel Literary Award for Young Writers (aged 35 and under) – becoming its final winner. The award, founded in 1980, has now closed, though the Australian’s book editor has indicated it will rise again with new sponsorship.

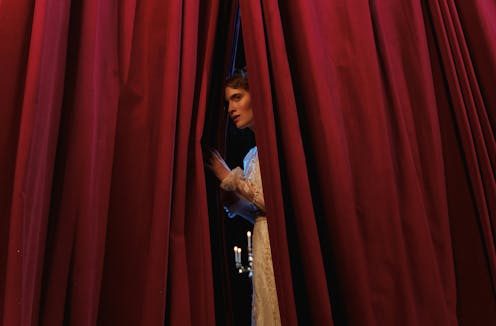

The book begins with a quotation from Hamlet: “The purpose of playing […] is to hold as ‘twere the mirror up to nature”. That seems a harmless enough choice for a novel about acting, but its meaning is clarified by the author’s prologue. Her narrator calls out the “cult-like” drama school’s “vicious, cutthroat” culture, embedded within a place that demanded its students “offer ourselves up to be dissected in the pursuit of becoming artists”.

Review: First Year – Kristina Ross (Allen & Unwin)

In a newspaper interview, the author said one motivation for writing First Year was to help others embarking on an acting career. “I searched for a story like this when I was a young actor in training and just never found it,” she said.

However, if the young Ross had read something like First Year before moving to Melbourne, she probably would have decided to defer her studies. Maeve, the name she gives to the character seemingly based on herself, continually stumbles through a combination of ignorance and immaturity. Her fellow students are older; some are university graduates while others have come from theatrical families. Even those not from Melbourne are familiar with the city and its culture.

A cultural novice

Maeve, fresh out of a Gold Coast private school, has never heard of the Australian Performing Group (APG) or the Pram Factory or been to La Mama, those great Melbourne theatrical institutions.

She is able to proclaim Juliet’s emotion-charged soliloquy from Romeo and Juliet for her audition, but until her second term, when she is an usher for Much Ado About Nothing, had never sat through an entire performance of a play by Shakespeare.

Her cultural interests are so limited, she has not read 1984, Wuthering Heights or Anna Karenina. Her protective parents pay for her to live in upmarket student accommodation, which further separates her from her colleagues. She may consider the living allowance her parents give her as “small”, but she is free of financial stress.

Drama training is intense. Ross describes it as needing to “become malleable to the method”. Yet Maeve is so inexperienced, so naive, that when she has to embrace a fellow student in class, she is overwhelmed by her emotions, as she was “unused to being in such close proximity to a man”.

“The man” is Saxon, who had flirted with her at her audition and names her “Juliet”, referring both to her audition piece and to her romantic naiveté. Her relationship with Saxon runs through the book as a variation of the classic romantic trope: girl gets boy, girl confuses acting with reality so loses boy, girl grows up.

Easy for predators to flourish

In class the students are challenged to move, to speak, to become the realities of the characters they are performing. The reader is introduced to teachers who oversee their education. Some of the portraits may be composite but the Head of School, the charismatic Quinn Medina, is drawn in such precise detail that it is relatively easy for insiders to guess the person on whom it is based.

In such an environment, it is easy for predators to flourish. And so we meet Yates, the famous actor and director, whose sexual harassment of female students is accepted as normal by the teaching staff. This is one of the implied questions raised by the author: is it worse to damage people by exploiting their bodies, or their minds?

Quinn uses her knowledge of the students, their circumstances and their private lives to ridicule them as she draws out their best possible performances, unconcerned at the cost of their mental health.

Maeve hears stories of a student who committed suicide after experiencing the intensive interior lives of others, but she also hears of the example of Sylvie, a student apparently so talented that her second-year performance led to a part in an upcoming film of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull.

Even before she meets Sylvie, Maeve becomes obsessed with her as an example of what she herself may achieve. Later, Maeve models her appearance, dress, and behaviour on Sylvie – including developing a serious cocaine habit. After all, as Quinn said, “the most direct entry point to the work was through living”. The combination of lifestyle, performance anxiety and emotional turmoil leads to an inevitable crash and burn.

In time, Maeve sees that students are used by Quinn as elements in manipulative games that may develop their craft as actors, but are more likely to stereotype them so they will be limited in the roles they are allowed to play. At the beginning of the year, a fellow student told Maeve “she fits the mould”, but now she sees that she is being moulded to play only the ingenue – and also, on occasion, to be the patsy.

After a student’s very public mental collapse, where the only words she can utter are Nina’s soliloquy from The Seagull, a senior teacher reminds the students, “Trust your instincts. After all, that is what drew us to you in the first place.”

Ross has indicated she sees First Year as a part of a series. While it reads more like a catharsis, I can see a sequel. But I do hope her writing is able to break out of what appears to be the autobiographical.

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.