If you’ve scrolled through TikTok or Instagram recently, there’s a good chance you’ve come across someone explaining how to “hack” your vagus nerve. On TikTok alone, videos with the hashtag #vagnusnerve, have collectively been viewed over 75 million times. Many purport to teach you how to use “vagus nerve stimulation” to alleviate anxiety, depression, and other ailments. But does the science support these social media claims?

What is the vagus nerve?

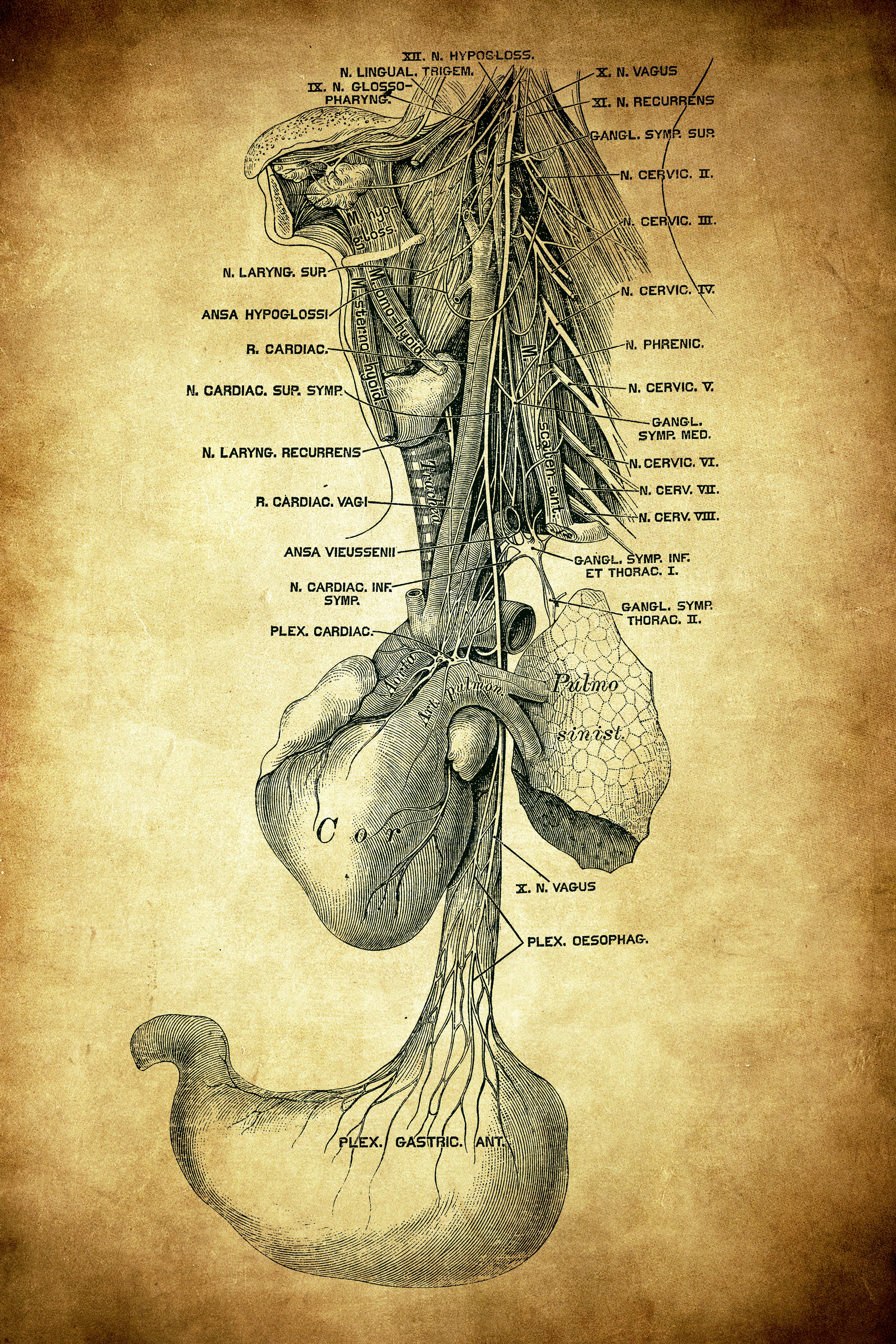

Contrary to what the name suggests, the vagus nerve isn’t one nerve. Instead, it’s two nerves that run from the brain stem, through the body, and down into the abdomen. Those two bundles of nerves each contain about 80,000 nerve fibers.

The vagus nerve is sometimes called the body’s “information superhighway” because it’s used to communicate both motor and also sensory information between the brain and the body’s organs. It’s the primary cranial nerve associated with the parasympathetic nervous system, which helps calm us down and relax; it's often referred to as the “rest and digest” state. It’s also involved in immune system functioning and inflammatory responses.

Eric Porges, an assistant professor in the University of Flordia’s Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, studies the vagus nerve. He tells Inverse that the vagus nerve has different branches that extend into different parts of the body. “Those branches affect different bodily systems and there are discrete physiological consequences from their engagement,” he says.

What is vagus nerve stimulation?

Vagus nerve stimulation is when electrical impulses are applied to the vagus nerve, either internally with an implant or externally with a handheld device, in hopes of alleviating the symptoms associated with an ailment. The electrical impulses produced by the device stimulate the vagus nerve, which then sends a signal to the brain and other organ systems. It can also travel to a part of the brain called the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), Porges explains. The NTS has a broad range of functions but can mediate some neurotransmitter systems, like those regulating dopamine and epinephrine.

The FDA has approved implantable devices for the treatment of intractable epilepsy, depression, opioid withdrawal, stroke rehabilitation, migraine, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Kevin Tracey, a neurosurgeon and president of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Northwell Health’s research center in New York, identified the vagus nerve’s connection to immune responses in the 1990s. Since then, he says, VNS implants have shown real promise.

“We know that some of these [vagus nerve] fibers travel from deep in the brain and coordinate the immune system’s inflammatory response in the spleen,” Tracey says. “So we know these fibers have the capability to stop inflammation.”

VNS implants, he says, can act like brakes in a car by pausing or otherwise altering the car’s movement. The company with which Tracey is affiliated, Northwell, has ongoing VNS trials and has seen some success in treating Crohn’s Disease.

“We know that putting these [VNS stimulators] in some patients has put them into clinical remission from their inflammatory disease,” he says.

Because of VNS’s effect on inflammation, such treatments may also be helpful for people with PTSD. Although we don’t always think of PTSD as an inflammatory response, research has shown that people with PTSD have higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers than people without the disorder.

Researchers at Emory University conducted a pilot study analyzing the effect of VNS on people with PTSD. Nine participants underwent either VNS stimulation and 11 underwent a sham procedure. Three months after the treatments began, the researchers found that the participants who received VNS had, on average, a 31 percent reduction in PTSD symptoms compared to the control group.

While this is promising, there are still many outstanding questions about VNS, Tracey says. For example, we don’t fully understand the specific mechanisms by which these implants or handheld devices have such a profound effect, nor can we generalize that such treatments would be universally effective for everyone with a given condition.

“When you start VNS by putting electricity in the body of a patient, you may be stimulating more than just the vagus nerve. So there are variables there that make it hard to completely understand the technical mechanism by which VNS is effective.”

“But I think it's inevitable that VNS will benefit millions of patients in our lifetimes,” Tracey says. “It’s really inevitable.”

Wait, but what about all that vagus nerve stuff on TikTok? They aren’t using handheld devices or implants

There are ways to activate your vagus nerve without an implant or other device, however, they’re not well studied.

Some of the techniques that are thought to stimulate the vagus nerve and engage the parasympathetic nervous system are:

Meditation and breathwork: research shows that these practices can help lower your heart rate and improve cortisol levels.

Exercise: Studies have found that exercise may activate the vagus nerve. A 2019 study in mice found that the dopamine release and anti-inflammatory benefits of exercise may be induced by vagus nerve activation.

Cold water immersion: Research has shown that immersing oneself in cold water can slow heart rate and direct blood flow to the brain. However, if you, like most people, aren’t able to or would prefer not to jump into a tub of cold water in the middle of your workday, cold stimulation on the lateral neck and chest can activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

Other techniques like “vagus nerve tapping”, which has made the rounds on TikTok, where people tap on their chest in the hopes of activating their vagus nerve, don’t have much evidence supporting it.

“I haven’t seen any evidence that tapping the chest impacts the vagus nerve,” Porges says. Though, “it’s probably a pretty innocuous practice if someone feels like it’s helping them. I would only be concerned if there was an underlying medical condition they weren’t addressing or they deployed these techniques in place of seeing an actual medical professional.”

“No treatment is universally applicable because maybe someone’s vagus nerve isn’t impaired. So it doesn’t mean what works for some will work for others. So that's an argument to keep doing more science,” Tracey says. “When I see wellness and health experts advocating a one size fits all solution, that should raise suspicion. Different people have different needs.”