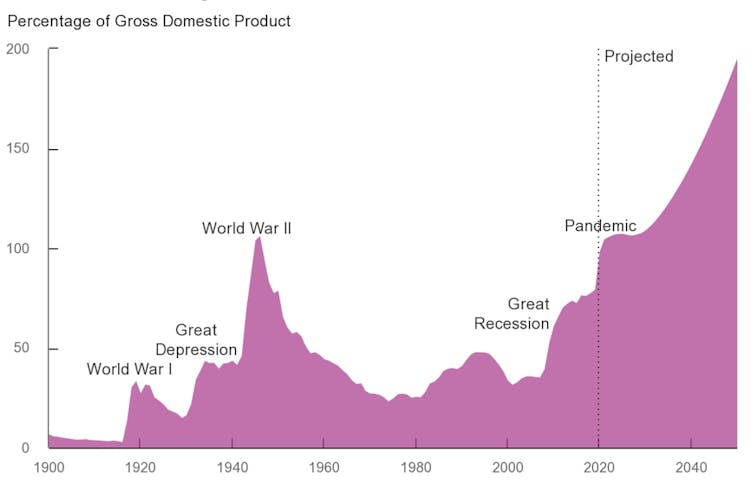

US federal debt currently stands at a staggering US$31.4 trillion (£25.2 trillion), the highest it’s ever been. That matters because it’s approaching the maximum limit that the government is legally allowed to borrow.

This is why Republican House speaker Kevin McCarthy recently delivered a speech at the New York Stock Exchange where he outlined his plan to address the concerns over this “debt ceiling”.

This isn’t the first time the US has been on the verge of reaching the debt limit. It’s been raised many times before, often through a compromise between Democrats and Republicans. But on this occasion, divisions in the Republican party could make it harder than ever for lawmakers to agree how to proceed – risking a government shutdown or default. Plus the national debt is nearly twice what it was the last time there was a debt ceiling crisis in 2013.

Right now, the cost of buying insurance against a federal default has reached its biggest number in over a decade. The US treasury is already deploying creative accounting to ensure that it can meet its fiscal obligations.

But that can only last for so long. By roughly July this year, according to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government could run out of money — and Uncle Sam wouldn’t be able to pay his bills.

Doomsday scenarios have become ubiquitous. Treasury secretary Janet Yellen has warned that failing to raise the debt ceiling would result in “catastrophe”. Mark Zandi, chief economist at US credit rating company Moody’s, has cautioned that inaction poses an “immediate threat” and could trigger a 2008-esque financial crisis.

The most recent showdown over the debt ceiling in 2013 resulted in a government closure for over two weeks, with hundreds of thousands of federal employees unable to work.

Who wins?

Both political parties are weighing in with the solutions they want. With a 2024 election on the horizon, both sides seem to want to fight and neither will be quick to give ground.

Republicans view the debt ceiling debate as an opportunity to strong-arm Democrats into rolling back spending, which some say could endanger Medicare and social security. Meanwhile, Democrats simply want to raise the debt ceiling, with a loose promise to revisit spending cuts later.

Republicans perceive this as a chance to paint Democrats as engaged in perennial reckless spending. A “deficits-don’t-matter” mentality won’t play in a general election, they’re betting. Democrats, by contrast, see an opening to assail Republicans as risking the stability and trust of the federal government. That fits into their larger criticism that “blow-up-the system” populists have highjacked the conservative movement.

Who’s running the show?

In the debt-ceiling debate, Democrat House minority leader Hakeem Jeffries insists that his colleagues are “not going to pay a ransom note to extremists in the other party”. Any lift to the debt ceiling would need to pass both the Republican-controlled House and the Democrat-controlled Senate. That makes compromise inevitable.

Yet the big question is what Republicans will accept. The answer will depend on who’s running the show: McCarthy or a band of Trump-supporting rebels determined to drain “the Washington swamp” of supposedly profligate officials and lobbyists.

McCarthy wants to reduce spending down to the same amount as in 2022, then curtail the growth in domestic spending at 1% per year over the next decade.

Yet McCarthy will be negotiating as much with the right flank of his party as with Democrats. He’s not in an enviable position.

US federal debt: 1900 to 2050 (projected)

Fiscal hawks want big cuts to discretionary outlays. Even defense expenditures could be on the chopping block. That places McCarthy in a tough spot as he tries to reassure more mainstream Republicans that America’s commitment to Ukraine isn’t waning.

In the coming weeks and months, we can expect lots of back-door wrangling among Republicans before McCarthy even gets to the bargaining table with Democrats. Hardliners have leverage precisely because the GOP majority in the House is so razor-thin.

McCarthy has already been sapped of much of his power because of all the concessions he had to make just to get the speakership. The concern is that some of his Republican counterparts will bind his hand so much that compromising across the aisle will be impossible.

Republicans have a point that Washington keeps kicking the can down the road on the debt. At the same time, they’ve also been guilty of fattening the deficit when they’ve controlled both Congress and the White House.

Democrats are right that risking default could be calamitous. Yet the Biden administration has also hastened the budget crunch by pushing through huge spending initiatives, including the US$1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue bill.

In light of the risks, it’s likely that the two parties will ultimately meet in the middle before default. But given the hyper-polarised climate in Washington, that’s not a foregone conclusion. And even if an agreement is reached, it’s likely to be pushed back to the eleventh hour. McCarthy thought that the 15 rounds it took him to secure the speaker’s gavel was tough. Getting to “yes” on the debt ceiling might make that look like a cakewalk.

Thomas Gift does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.