The four biggest moons of Uranus may harbor salty oceans below their frozen surfaces, a new study suggests.

Scientists taking a fresh look at 40-year-old data sent home by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft say that the satellites Titania and Oberon, which orbit the farthest from Uranus among the group, may have buried oceans 30 miles (50 kilometers) deep, while those of Ariel and Umbriel may be 19 miles (30 km) deep. The new research explains how the persistent internal heat of the Uranian moons and a few chemicals could make them watery worlds despite their location in the frigid outer reaches of the solar system.

"Finding oceans in the Uranian moons would increase the prospect that [...] ocean worlds are frequent in our solar system, and maybe — by extension — in other solar systems," Julie Castillo-Rogez, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and lead author of the new study, told Space.com in an email on Thursday (May 4).

Related: Uranus' moons: A guide to the ice giant's strange tilted moons

Early in their histories, Uranus' five largest moons — Titania, Oberon, Ariel, Umbriel and Miranda — likely hosted substantial oceans ranging from 62 miles to 90 miles (100 km to 150 km) deep, researchers said.

"If the moons had benefited from long-term heating from their planet, then they could have maintained a thick ocean," Castillo-Rogez said.

For example, the Jupiter moon Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, both of which harbor big subsurface oceans, flex their innards and icy crusts in response to the strong gravitational pull from their host planets. Scientists think this tidal heat helps the moons maintain their subsurface water as a life-friendly liquid. But Uranus' tug is far weaker than that of Saturn or Jupiter, so oceans on even the planet's four largest moons are "mostly frozen by now," Castillo-Rogez said.

To understand more about how Uranus' largest moons may have evolved, her team built a model by gathering findings from NASA missions that studied other ocean worlds. These included Saturn's moon Enceladus, as observed by the Cassini mission; the dwarf planet Ceres, as revealed by Dawn; and Pluto's largest moon Charon, which New Horizons observed during its epic Pluto flyby in 2015.

The team's model revealed that the Uranian moons likely hold "thin oceans with high salt concentrations," according to the new study. This would be thanks to limited internal heat left over from their births, as well as considerable ammonia, whose antifreeze nature helps keep water in its liquid form even in very low temperatures.

The oceans on these Uranian moons have about 150 grams of salt for every liter of water, the researchers estimate. In comparison, Utah's Great Salt Lake in the United States is twice as salty, but life still manages to thrive in and around it.

The jury is still out on the ocean potential of Uranus' fifth-biggest moon, Miranda. Although previous research hinted at a hidden ocean to explain intriguing charged particles blasted into space, Miranda is so small that its internal ocean very likely froze just a few million years after it formed, researchers say in the latest study.

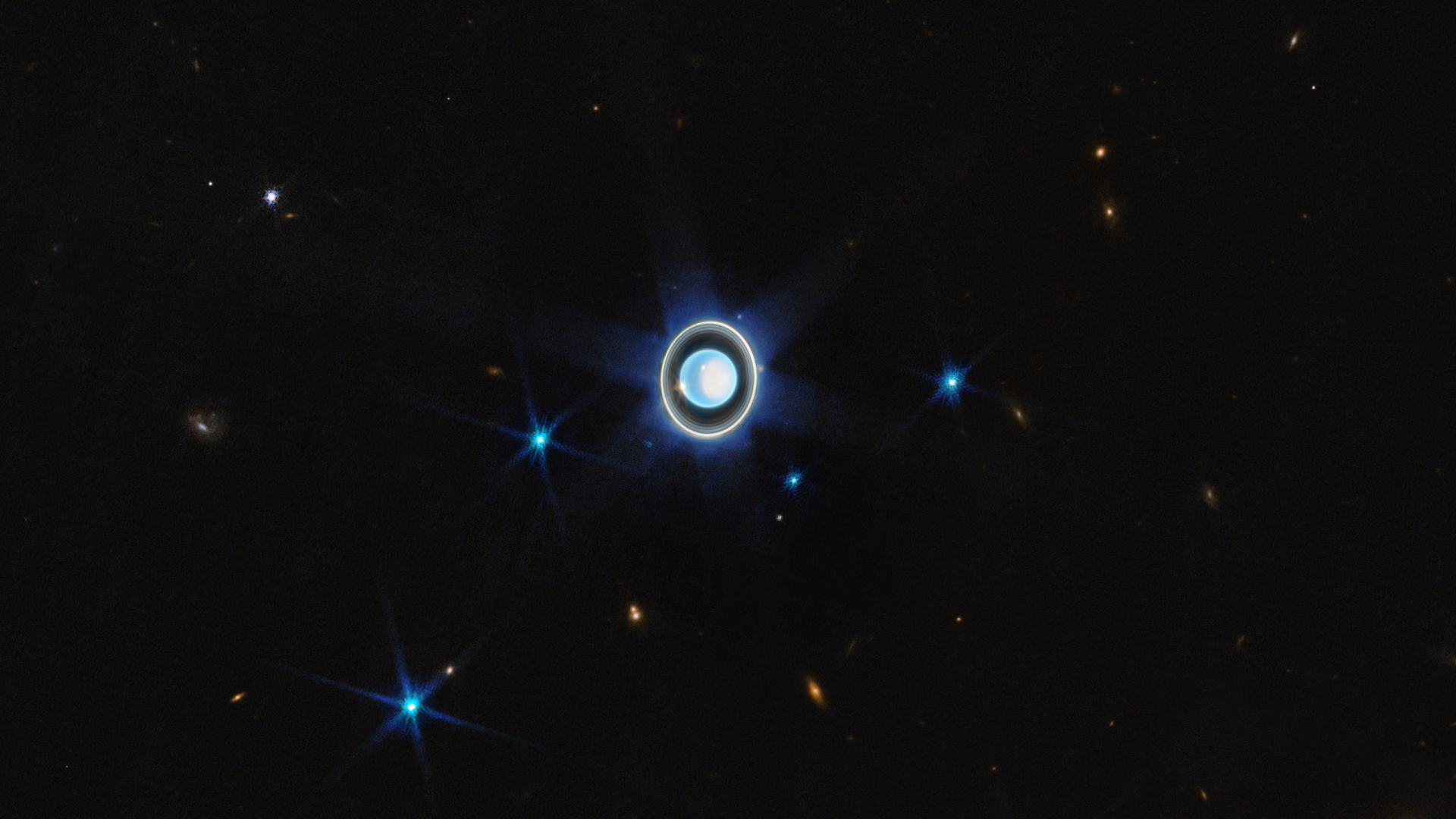

So far, Uranus has been briefly visited by only Voyager 2 — which spotted 10 new moons and a couple of new rings around the ice giant — during its January 1986 flyby. But Uranus may get more attention in the not-too-distant future, in part because exoplanet research has revealed that ice giants are among the most common, yet least understood, planets in the galaxy.

NASA is developing a potential mission to the planet, currently given the placeholder name of Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP). As that moniker suggests, UOP would include an orbiter to gather data about the ice giant and its moons from afar and a probe that would drop into the planet's atmosphere for first-hand information, according to the mission concept.

The new study was published in December 2022 in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @skuthunur. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.