A hip-bone fossil found in France may have belonged to an early lineage of modern human Homo sapiens, one subtly different from present-day modern humans, a new study finds.

The fossil suggests that a group often thought of as solely Neanderthal in Europe may have consisted of Neanderthals and modern humans living together, the scientists noted.

Previous research in Europe suggested that the final phase of Neanderthal culture might have been a group called the Châtelperronian. Artifacts from Châtelperronian sites, which date to about 44,500 to 41,000 years ago, extend from northern Spain to the Paris Basin.

However, the Châtelperronian has inspired a great deal of controversy over the years from scientists who argued that its artifacts were actually modern human in nature. Prior work found that modern humans had made their way to Western Europe by about 42,000 years ago.

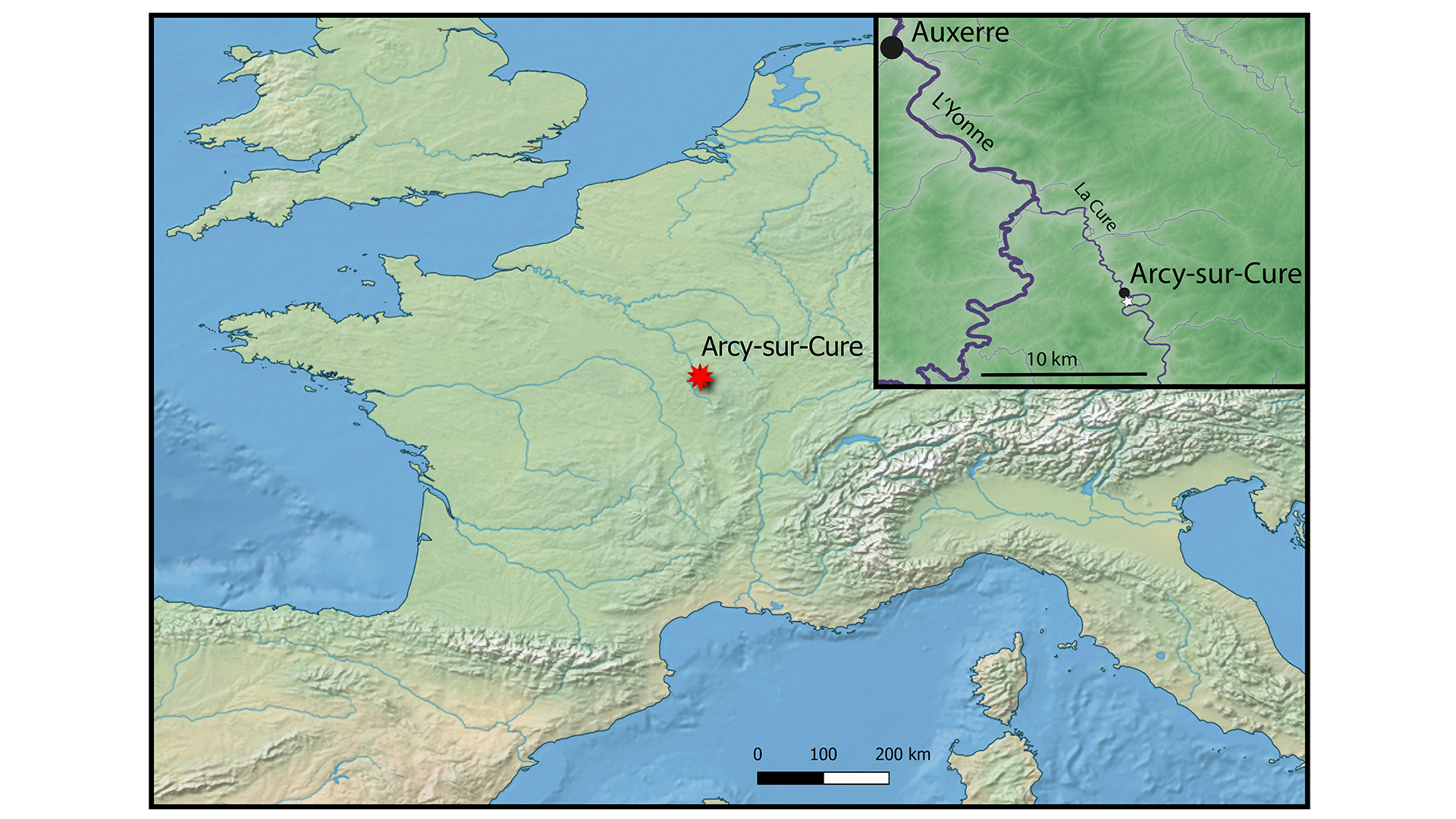

In the new study, the researchers focused on a key site for investigating the identity of the Châtelperronian: the Grotte du Renne cave in Arcy-sur-Cure, about 125 miles (200 kilometers) southeast of Paris. Scientists had previously discovered several Neanderthal remains within the cave's Châtelperronian levels.

Related: Unknown lineage of ice age Europeans discovered in genetic study

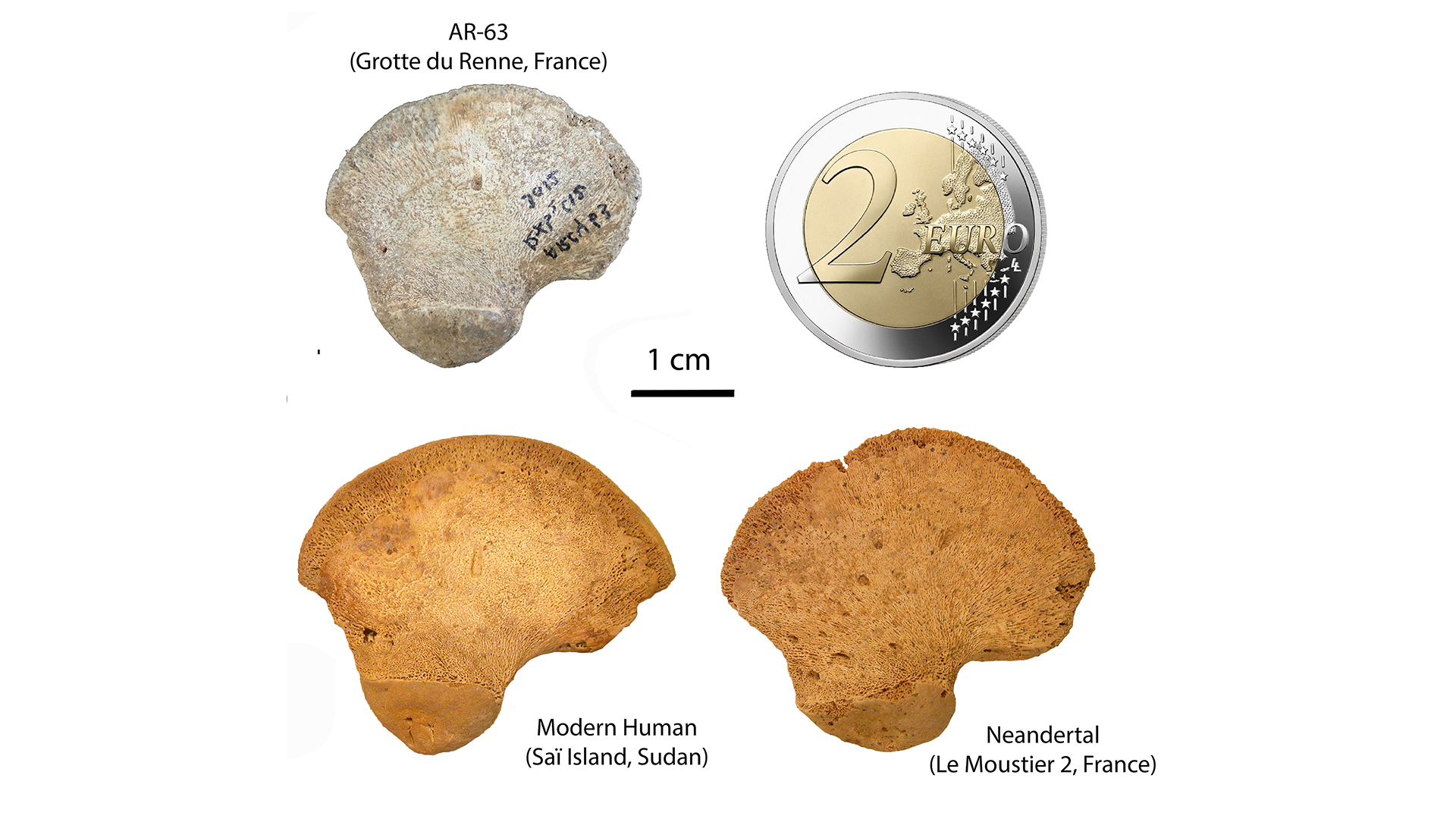

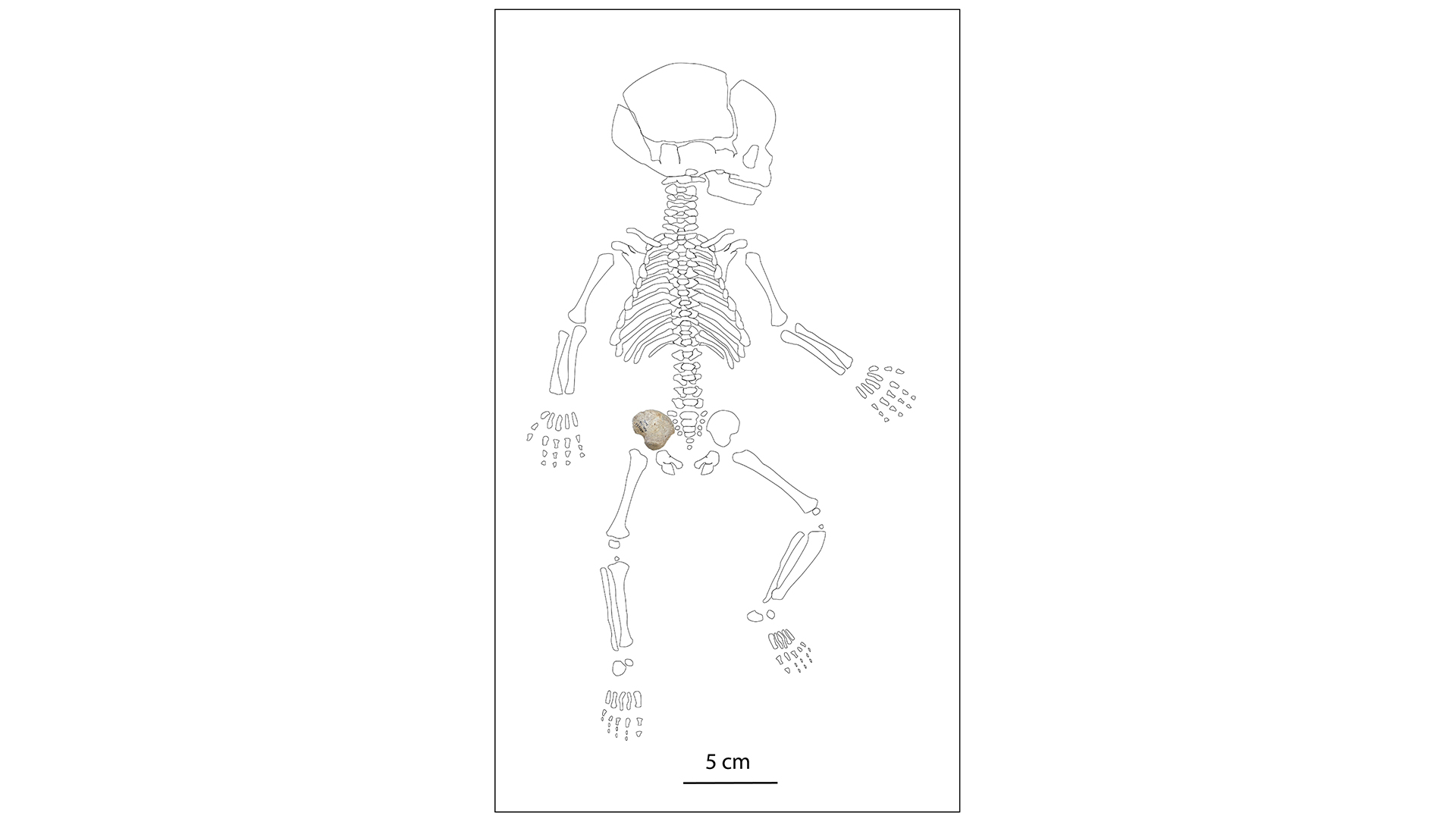

The scientists investigated a newborn's hip bone — an ilium, one of the three bones that make up the pelvic girdle. This bone, about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) wide, was found in a layer previously dated to about 40,680 to 42,335 years old. Scientists had found other remains there that DNA revealed were Neanderthal in origin.

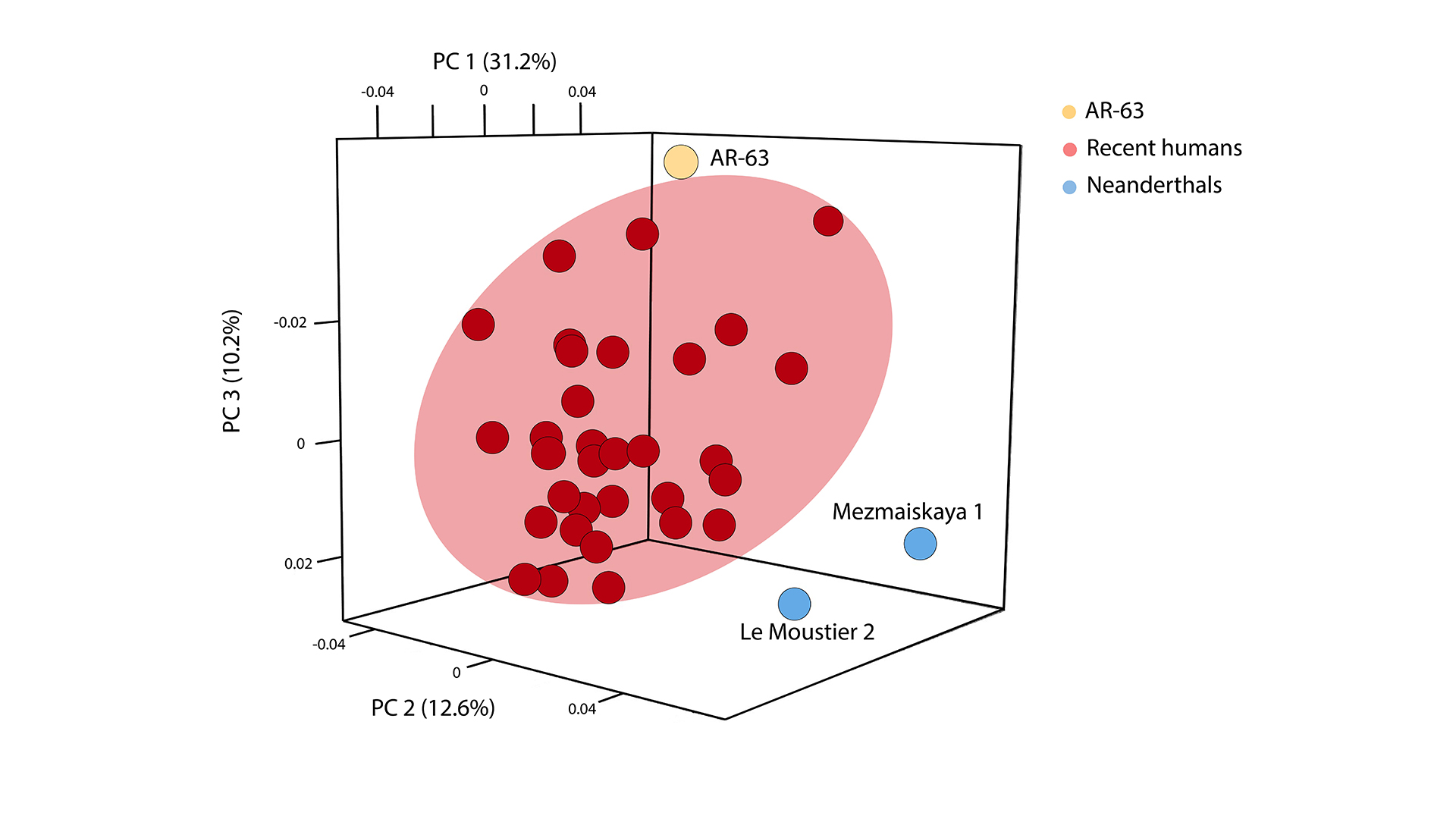

The paleoanthropologists compared this hip bone to the same bones in two Neanderthal babies and 32 present-day human newborns. They discovered that the Grotte du Renne fossil clearly differed from Neanderthal bones. It also was slightly different from those of recent modern humans.

"It is very surprising to have a Homo sapiens fossil from a Châtelperronian context," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who did not take part in the new study, told Live Science.

The researchers suggested that this hip bone belonged to an early modern human lineage that differed slightly from present-day modern humans. "We have found a new anatomically modern human lineage," study senior author Bruno Maureille, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux in France and head of research at France's National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), told Live Science.

The hip bone does not show any signs of disease that made it look different from typical Neanderthal or modern-human bones, Maureille said. One might argue the layer of dirt in which this bone was found might have been disturbed at some point, confusing its association with a Châtelperronian strata, but prior work suggested this layer remained largely intact over the millennia, he noted.

The simplest explanation for this early modern human hip bone surrounded by Neanderthal remains could be separate modern humans and Neanderthal groups sharing the same culture, Maureille said. Another possibility is a mixed group where both modern humans and Neanderthals lived together, he added.

"If the finding survives further scrutiny, then for me the most likely scenario is a clear demonstration that Homo sapiens populations lived in close proximity to Neanderthals during Châtelperronian times," Stringer said. "That, in turn, points to the likelihood of contacts between them at that time."

Recently, Ludovic Slimak, an archaeologist at the University of Toulouse in France, argued that the Châtelperronian were actually modern humans.

"If he is right, then it makes sense of the Homo sapiens fossil in a Châtelperronian level, but it would imply that the Neanderthal fossils there are either intrusive, or they represent a contemporary Neanderthal population that is represented more abundantly there, for whatever reason," Stringer said. "Regardless of the veracity of Slimak's controversial ideas, this new finding highlights continuing fundamental questions about the true nature of the Châtelperronian."

Future research can investigate more newborn bones from this time to shed light on their origins, Maureille said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Aug. 4 in the journal Scientific Reports.