When the EU’s heads of state and government come together in Brussels for their final European Council meeting of the year on December 14 and 15, their agenda is likely to be dominated by the war in Ukraine.

As you’d expect, the war has an agenda item of its own – but it is also central to discussions on enlargement, the budget and European defence. Decisions made at this meeting will have far-reaching implications – not only for Ukraine but also for the EU.

The EU has to balance its internal cohesion with its foreign and security policies, including preserving its appetite and capacity for further enlargement. This presents Brussels and member states with some important challenges.

First, Hungary’s prime minister, Victor Orbán, has been very clear that he does not support continued EU funding of Ukraine’s war effort. This is partly a gambit by Orbán to unlock approximately €22 billion (£19 billion) of EU aid to Hungary frozen because of concerns over judicial independence, academic freedom and LGBTQ+ rights in Hungary.

Another issue concerns the situation of Ukraine’s Hungarian minority, which Orbán claims has been neglected and discriminated against by Kyiv.

There appears to be some progress on unfreezing EU aid to Hungary, with the European Commission approving an initial payout of about €900 million in November. And, in terms of minority rights, a bill addressing this issue was signed into law on December 8 as part of a tranche of legislation designed to ease Ukraine’s entry to the EU.

But given Orbán’s close relationship with Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, it is not clear whether this will be enough to get Orbán to drop his veto.

Should the Hungarian premier persist, the EU’s next budget is also in peril. This would prevent the unlocking of €50 billion of aid for Ukraine and block a proposed increase in the EU’s defence spending.

This will have to increase significantly in the years to come because developing European capabilities to deter future Russian aggression is essential for the EU’s security.

A potential second Trump presidency puts question marks on US commitments to Nato and there is a danger of further increasing tensions with China in the Pacific distracting the US from Euro-Atlantic defence.

Where does this leave Ukraine?

These and other challenges faced by the EU leave Ukraine in increasing peril. With US funding running out by the end of the year and no clear path to its renewal, Kyiv depends more and more on its European partners. Equally worrying, new aid commitments are now at their lowest level since January 2022.

The EU has overtaken the US as the largest donor of committed military aid. However, this is not an indication of broad European support, but the result of the efforts of a small core of countries, including Germany and Scandinavia.

Military aid is essential to Ukraine’s survival, but it is not sufficient. If the EU does not approve its proposed €50 billion support for Kyiv, the country’s economic survival would be at risk because of the massive budget deficit that Ukraine keeps accumulating due to its war effort.

A failure by the EU to open accession negotiations would also exacerbate the blame game at the top between Ukraine’s political and military leaders and the squabbling between government and opposition over Kyiv’s war strategy.

Is Kyiv fighting a losing battle?

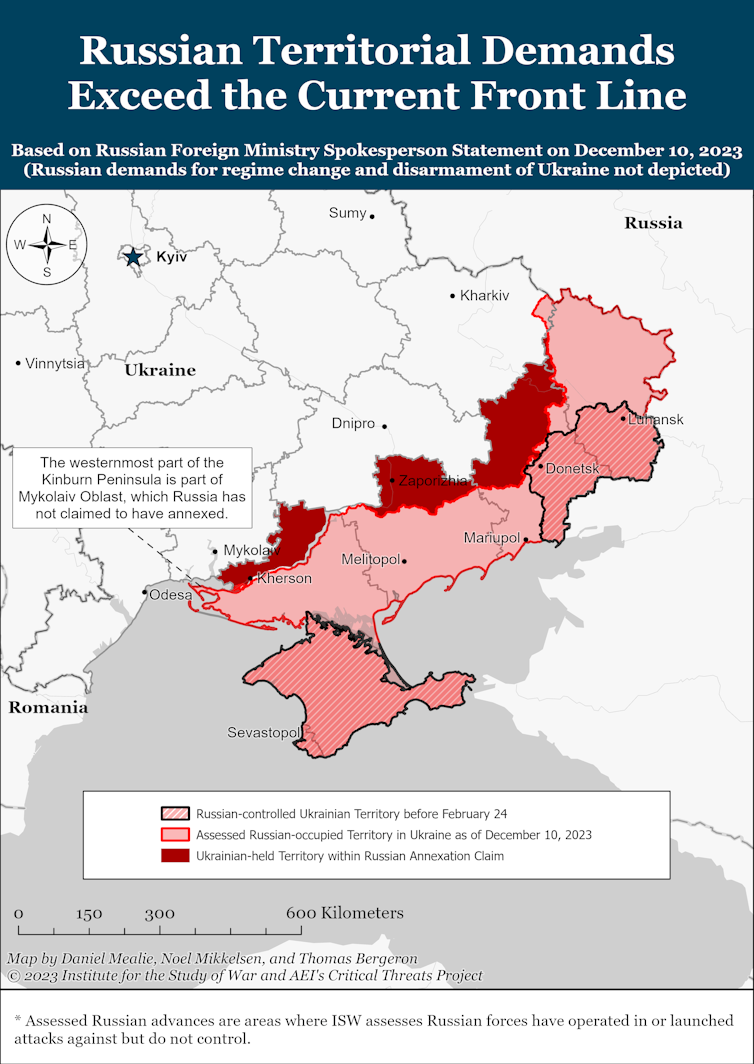

For now, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has doubled down on his efforts to defeat Russia militarily by announcing more, and more effective, mobilisation of troops. But, in light of a failed counteroffensive this year, he has also conceded that more needs to be done to increase defences across the entire almost 1,000km frontline with Russia.

With Russia announcing a further increase in its armed forces by 170,000 new recruits to over 1.3 million servicemen in total, there can be little doubt that the shift on the battlefield in Russia’s favour is gaining momentum.

Even if the European Council meeting in Brussels later this week delivers the opening of accession negotiations and more financial aid, further territorial losses, such as around Avdiivka, and another Russian campaign against Ukraine’s critical infrastructure over the winter would prove difficult for Kyiv and raise more questions about the sustainability of western support.

This leaves Ukraine and the EU with difficult choices to make. The accession process will be long, costly and protracted. Major challenges lie ahead in terms of the necessary reforms Kyiv needs to carry out, the financial burden that the country’s post-war recovery will involve and the difficulties that Ukraine will face when it comes to reintegrating liberated territories and populations.

Depending on when and how the war will end, there are four scenarios that Kyiv and Brussels can contemplate.

If the war ends soon and with a ceasefire that freezes the current frontline, a German scenario of prolonged division but eventual reunification is conceivable that would integrate at least part of Ukraine early into the EU, probably with credible security guarantees against further Russian aggression.

Along similar lines, a Cyprus scenario could unfold where the EU membership issue is fudged at the time of accession. In both cases, the government-controlled part of Ukraine could see further democratic consolidation and economic recovery.

Two alternatives are possible to think of if the war ends soon and with the restoration of all or part of currently Russian-occupied territories to Ukrainian sovereignty.

A Croatia-style scenario would imply a military defeat of Russia and reintegration of the country as a result. Given the current realities on the battlefield, this is highly unlikely. A Bosnia-style negotiated settlement leading to a dysfunctional state and no reintegration, by contrast, may be more likely, but is undesirable because it would all but rule out EU accession.

The challenge for EU leaders at their year-end summit will be above all to find a way forward that enables Ukraine to survive militarily and economically what will be a challenging winter and year ahead. This could then open a pathway to both a negotiated settlement with Russia and EU membership.

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU's Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Trustee and Honorary Treasurer of the Political Studies Association of the UK, a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London and Co-Coordinator of the OSCE Network of Think Tanks and Academic Institutions.

Tetyana Malyarenko does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.