The Ukrainian advance into Russia’s Kursk oblast took almost everyone by surprise. Perhaps not the Russians stationed on the border, who reportedly tried to warn of a Ukrainian troop buildup, but the rest of us who watch the conflict closely did not think the Ukrainian army – under increasingly severe pressure in Donetsk oblast further south – had the spare manpower and kit to launch this operation.

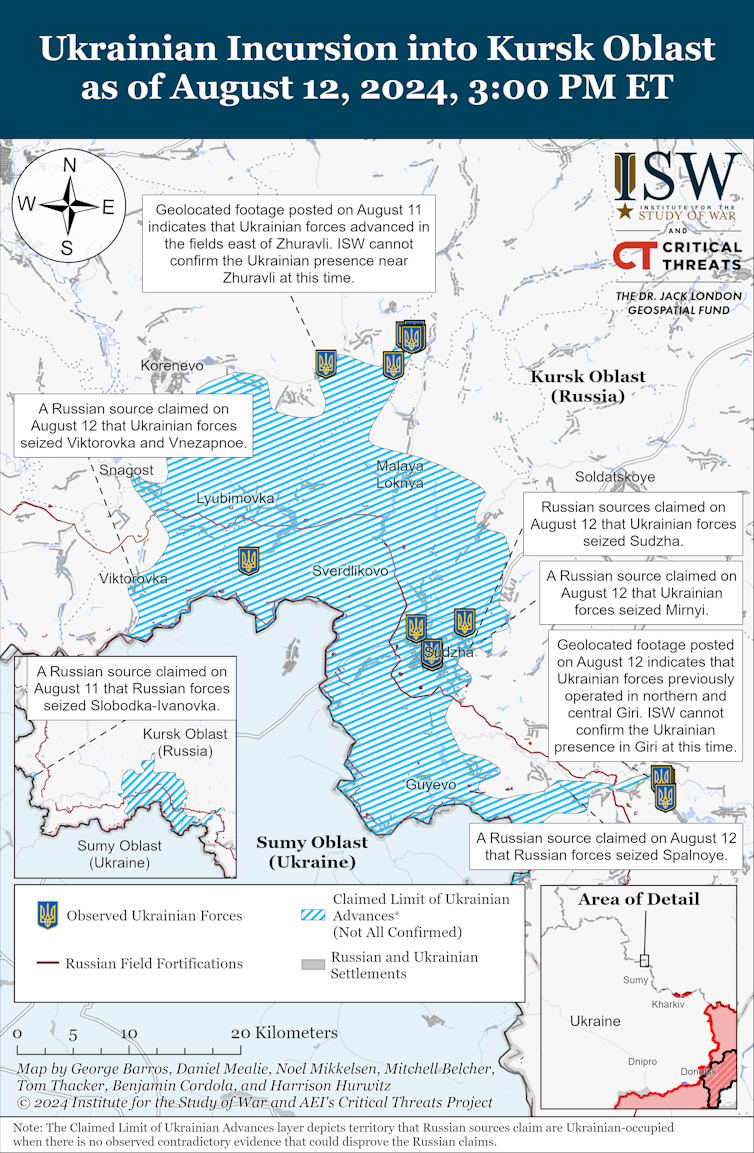

So far it has been successful, advancing up to 30km in some directions and creating a salient inside Russia some 40km wide. An area of about 800 square kilometres has been seized so far according to the Institute for the Study of War in the greatest loss of western Russian territory since April 1944. How have the Ukrainians done it, and what might happen next?

First, they have had good operational security (opsec). Remember the US Discord leaks last year that gave away the battle order of Ukraine’s summer 2023 offensive forces? Well, thankfully, this time that hasn’t happened, and America even initially deemed surprise that the Ukrainians had attacked into Russia, before later endorsing the move. Better opsec means a less prepared enemy, as was the case when Ukraine’s lead brigades rolled over the border early on August 6.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, they picked a weakly defended stretch of the border to attack, near the Russian town of Sudzha, nearly 200km northwest of the closest frontline in Kharkiv, and 350km from the main frontline.

On the main frontline, Russia has managed to generate a persistent intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capability (ISR), using drones and pairing this with guided missiles and bombs to make it very hard for the Ukrainians to move without being targeted. This has made it difficult to mass forces and manoeuvre in the way needed to achieve a breakthrough. Russian defences and force ratios are also strong here.

But in moving the point of attack to a relatively unguarded stretch of border, Ukraine has managed to negate these advantages and set the conditions for an operational breakthrough. In Kursk, the Ukrainians are back on the offensive and the mechanised brigades are rolling again, causing chaos and confusion as they get behind the Russian lines and fan out.

It has been an impressive move. On top of concentrating elements of six brigades, many with western tanks and armoured fighting vehicles, without being attacked, they have have used deep reconnaissance groups to cause chaos and confusion ahead of the main thrusts. Crucially, they have also managed to establish and maintain an air defence (AD) and electronic warfare (EW) “bubble” over their advancing forces. The AD bubble makes it much more difficult for Russian fast jets and helicopters to operate near Ukrainian forces, while EW jams the frequency spectrums needed for Russia to operate it’s drone-based ISR.

We’ve also seen the Ukrainians adapt tactically, successfully using first-person-view (FPV) drones against helicopters for the first time. Russia’s attack helicopters were crucial in breaking up the 2023 summer offensive, so this move could have a major impact on Russia’s ability to use helicopters near the frontlines. They’ve also used their own fast jets in the close air support role, hitting ground targets in Russia.

The cumulative effect of this combined arms coordination is that Russian commanders arriving to relieve Kursk have spoken of how difficult it will be to dislodge the Ukrainian army quickly.

The damage done

According to one “top Ukrainian official”, the operation aims “to stretch the positions of the enemy, to inflict maximum losses and to destabilise the situation in Russia”. The unnamed official added that the attack has “greatly raised our morale, the morale of the Ukrainian army, state and society”.

The morale boost is well apparent, but with Russia actually increasing its push into Donetsk recently, it is not clear if the Kursk operation will bring any relief for Ukraine’s beleaguered defenders there.

Either way, this kind of successfully executed operation doesn’t just happen. It will have been carefully planned for months. And that timeline perhaps gives an indication of its ultimate strategic objective. Months ago, Donald Trump was odds-on to become the next US president. He has stated he will stop aid to force Ukraine to negotiate with Russia. So perhaps the strategic aim is to seize and hold Russian territory as leverage in any future negotiations. Significantly, the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky has congratulated the armed forces for increasing the size of Ukraine’s “exchange fund”.

Will they stay or will they go?

There have been reports of Ukrainian troops using mechanical diggers to build trenches inside Russia, which could indicate plans to try to defend at least some of the seized territory. Meanwhile, the Russians are doing similar, with a view to stabilising the lines. This will be their short-term goal, followed by the attrition of Ukrainian forces and the reducing of the pocket occupied by the incursion.

But this will take time. Looking ahead, absent another Ukrainian surprise, an unlikely Russian military disaster, or a political deal, the most likely course of action is that Russia’s numerical advantage will begin to tell. Then Kyiv will have a decision to make: to withdraw troops back into Ukraine or to prepare defensive lines on Russian territory further west. As a withdrawal while in contact with the enemy is notoriously tricky, this would be better done sooner rather than later.

They could try to hold what they have but this is reliant on reinforcing and sustaining the salient, and risks getting badly mauled by the Russians over time. Finally, there could potentially be some sort of quick deal solution: Ukraine withdraws in return for a Russian withdrawal from the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, which could provide sorely needed energy this winter, for example.

Ukraine’s Kursk offensive is high risk and high stakes. So far, the operation has been successful, but its eventual outcome – rather than events a week in – will determine its wider importance. But Ukraine has shown the west it can use their equipment and its own jets inside Russia without major escalation. It may also contribute to another round of Russian mobilisation, increasing the political risk to the Kremlin.

And one thing neither side will forget is how easy it was for Ukraine to roll over the weakly protected Russian border and embarrass Putin.

Patrick Bury served as a British Army air assault infantry officer and was subsequently an analyst at Nato.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.