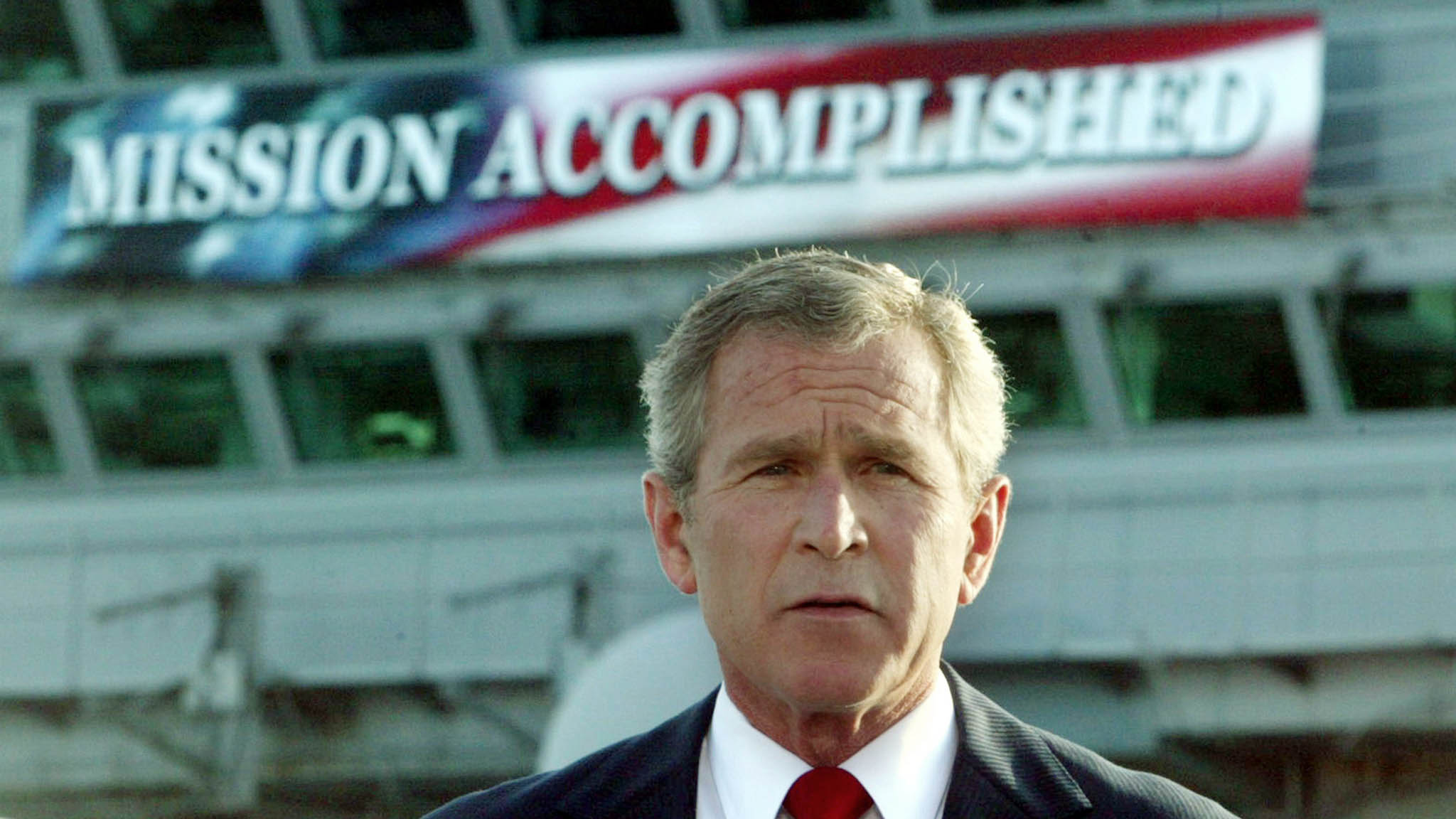

Twenty years ago, on May 1, 2003, then-United States President George W Bush announced the end of major combat operations in Iraq, a giant banner behind him triumphantly screaming, “Mission Accomplished”. Six weeks earlier, the US had invaded the Middle Eastern country illegally.

As US armour was rolling into Iraqi cities, international news networks replayed over and over again a scene from April 9 that year that in hindsight seems loaded with dramatic irony.

The toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad’s Firdos square — an event that turned out to be stage-managed — was meant to symbolise the liberation of Iraqis and the end of the Ba’ath Party’s 35-year-long rule in Iraq. Yet it was not the grand finale of the US invasion but rather the prelude to a long and bloody revolt and armed uprising.

The US occupation that lasted eight years created aftershocks of regional instability and left hundreds of thousands of Iraqis dead — so many that no one has an exact count.

Like the US-led coalition in Iraq back then, the Russian government expected its illegal invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to end with a quick and decisive victory.

Fooled by a sense of its own invincibility, the Russian army entered Ukraine as if on parade, in long columns that became easy targets for US-made Javelin missiles. They expected to be marching through the streets of Kyiv within days, but a year later, the Russians remain bogged down in a protracted and bloody war.

So did Russian President Vladimir Putin end up repeating the mistakes — and for many, the crimes — of Bush in Iraq 20 years ago? How much do these two epoch-defining invasions have in common? What are the differences?

The short answer: The parallels run deep, from the false pretexts under which they were launched and the failings of the United Nations system that the wars showed up, to the use of private military contractors. But key differences exist in the deeper motivations that triggered the wars, said military historians and analysts. And the US military proved more effective at fighting a conventional war in Iraq than Russia has in Ukraine.

‘We create our own reality’

Both the US-led coalition in Iraq and Russia in Ukraine were led to war by unbridled hubris — that is a “key element” that these two conflicts have in common, said Ibrahim al-Marashi, professor of Iraqi history at California State University. Both belligerents assumed it would be easy to launch “decapitation” attacks and replace the governments of the countries they were invading with friendly regimes that would simply serve their interests.

“In the US case they achieved the decapitation, but they really misread the Iraqi population,” says al-Marashi. “The US thought they would be greeted as liberators overthrowing Saddam Hussein, and that didn’t happen. What did Russia think? That the Ukrainians would also welcome them as liberators for overthrowing this so-called ‘fascist regime’.”

The outcome was the same in both cases — a “dogged national resistance that humbled both powers,” he said.

The hubris showed up in many ways.

Once senior Bush administration officials had made up their minds about invading Iraq, their single-minded determination to topple the Iraqi regime rendered them oblivious to the unintended consequences of war, said analysts.

It also blinded them to inconvenient truths — something neatly encapsulated in what a White House official reportedly told journalist Ron Suskind. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality,” the official said.

Creating their “own reality” meant ignoring international law and the United Nations Charter that the US and Soviet Union were original signatories to. The inability to stop the two bellicose powers from attacking sovereign states starkly exposed the weaknesses of the post-World War II international order.

Both Russia and the US went to war off the back of bogus pretexts — alternate realities they created. In the case of the US and its closest ally in the invasion of Iraq, the United Kingdom, dubious intelligence painted Saddam Hussein’s Iraq as a harbourer of al-Qaeda, a hoarder of weapons of mass destruction, and an all-around international bogeyman.

Al-Marashi has firsthand experience of this. A paper he wrote was plagiarised by the UK government in a 2003 document used to make the case for invading Iraq — the so-called “dodgy dossier”. Al-Marashi said his work was used in “constructing the image of a dictator who had to be overthrown”.

Russia constructed the image of a hostile administration in Kyiv that needed to be overthrown and took that lie to its absurd outer limits, portraying Ukraine’s Jewish president Volodymyr Zelenskyy as a depraved addict presiding over a government of neo-Nazis.

“The first ‘reason’ for Putin taking Ukraine was that he was saving the Ukrainians from this drug-crazed criminal Nazi gang running the country,” says Margaret Macmillan, professor of history at the University of Oxford. “And when it turned out that a lot of Ukrainians were supporting the drug-crazed criminal gang the war was now on the Ukrainians themselves, and then there was talk of re-educating them.”

Different backdrops

As a state where power is concentrated in one man, Russia’s war in Ukraine is Putin’s war — the brutal incarnation of his own imperial designs, said experts.

According to Jade McGlynn, research fellow at the Department of War Studies at King’s College in London, and author of the book Russia’s War, the invasion of Ukraine “at its heart is a war over identity and conceptions of the [Russian] nation”.

Putin “conflated himself with the power structures of Russia,” said McGlynn, and “constructed a post-Soviet Russian identity that is very dependent on Ukraine and the idea of a greater Russia”.

For al-Marashi, who used to teach at Ukraine’s Ivan Franko University, Russia’s war has an undeniably imperial aspect to it that can be traced back to Ukraine’s incorporation into the Russian empire and deliberate policies of “Russification”, which attempted to deny Ukrainian culture and identity in the 19th century. This “imperial mindset” has a long history to it, said al-Marashi, from Catherine the Great’s description of Ukraine as ‘New Russia’ all the way to Putin. “Those are imperial linkages that I don’t think you can deny,” he said.

The US’s imperial mindset towards countries it has invaded and occupied is also hard to ignore, said experts. But there is a key difference highlighted by the contexts that set the stage for the wars in Iraq and Ukraine.

Russia, said Macmillan, “is the last standing European empire”. But it is a crumbling empire, and the speeches and revisionist historical treatises that laid Putin’s ideological groundwork for the invasion of Ukraine are often shot through with a sense of historical loss. Putin has lamented the breakup of the Soviet Union as a “genuine tragedy” in which “tens of millions of our fellow citizens and countrymen found themselves beyond the fringes of Russian territory”.

His war arose out of the perceived loss of Russia’s greatness, its humiliation and betrayal at the hands of the West, and the desire to reclaim Russia’s place in the world, according to experts. “Putin was a KGB agent when he witnessed the collapse of the Soviet empire from East Germany,” said al-Marashi.

But it was very different for Bush, who “inherited the windfall” of the end of the Cold War and was “riding the emergence” of the US as the superpower in a unipolar world.

Unfinished business

According to al-Marashi, the 2003 invasion of Iraq came at a “unique historical moment” for the US, when its hegemony was relatively unchallenged and it “sought to reshape the world” in its image.

When Bush ran for president, he was focused on domestic affairs, not foreign intervention, al-Marashi pointed out. But that changed with the 9/11 attacks, which emboldened the administration’s hawks, who felt that the US had unfinished business in Iraq.

In much the same way, the Putin regime had unfinished business in Ukraine. Putin, said experts, felt the need for a lasting solution to the Ukraine question that had plagued Russian nationalists since the Soviet breakup in 1991. That question — namely, what to do about Ukraine drifting towards the West’s embrace — had become ever more pressing since the 2014 war in the Donbas.

Russia’s “Vietnam” — the disastrous 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, and retreat nine years later — was a cautionary tale about underestimating the resistance of an invaded people. But the memory of that war had faded, and for Russia’s foreign policy hawks, there were more encouraging historical examples closer to hand: the brutal suppression of Chechen independence, and more recent military successes in support of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad.

For Bush Junior, returning to the Middle East was an opportunity to finish off what his father started in the First Gulf War. Key officials and ideologues of the second Bush administration had served under the elder Bush including his vice president, Dick Cheney, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, and US trade representative Robert Zoellick. They had long advocated for US military intervention abroad.

Wolfowitz, Armitage and Zoellick — three leading “neocons” — together with another key war architect, Bush’s Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, were signatories of a letter to President Bill Clinton in 1998 calling for regime change in Iraq.

“The only acceptable strategy is one that eliminates the possibility that Iraq will be able to use or threaten to use weapons of mass destruction,” the letter read. “In the near term, this means a willingness to undertake military action as diplomacy is clearly failing. In the long term, it means removing Saddam Hussein and his regime from power.

“In any case, American policy cannot continue to be crippled by a misguided insistence on unanimity in the UN Security Council.”

From Blackwater to Wagner

Security concerns, although they turned out to be highly exaggerated, played into the decisions of the US and Russia to embark on their illegal invasions.

Moscow has pointed to its fears of NATO expansion and the existential threat posed by a hostile Ukraine, describing its neighbour as merely a proxy for the West. It is, in Putin’s view, the latest episode in a long history of Western attempts to cripple Russia.

To some extent, it has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. European support for NATO is far greater than before the invasion, and Russia is more isolated, more economically vulnerable, and faced with biting sanctions.

Similarly, in the aftermath of 9/11, paranoia crept into the US establishment. The first major attack on the US mainland exposed the vulnerability of the world’s sole superpower and left the US public deeply shocked. Although Iraq had nothing to do with the attack, Americans “were prepared to believe the government if it told them Iraq was responsible,” Macmillan said.

Ultimately, both wars left the countries that started them — and the world at large — less secure than before, and as the costs and casualties began to mount, their citizens became predictably wary. The aftermath of 9/11 saw jingoism reach a fever pitch in the US but also galvanised an anti-war movement. By the end of Bush’s final term, public support for the war had plummeted.

It is much harder to gauge Russian public opinion — criticism of the war has been banned and early shows of public disapproval were ruthlessly stamped out — but the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Russians fleeing abroad to avoid the draft gives some indication of the public mood.

When the war in Donbas started in 2014, “there was a nationalist revival”, said McGlynn, “you saw people volunteering to go off to Donbas.

“In 2022 it was different, people were anxious”.

Yet again, Putin appears to have followed Bush’s example.

The US did not rely on conscription to fight its war in Iraq, but was nevertheless wary that a steady stream of body bags for regular troops would take a major toll on public opinion. Its widespread reliance on private military contractors in Iraq, however, helped solve that problem.

The war in Iraq presented a boon for security firms like Blackwater, whose mercenaries were implicated in civilian killings. Russia has followed suit in Ukraine, outsourcing its war to private companies like the notorious Wagner Group that has recruited widely from prison populations.

Newly recruited, poorly trained prisoners have been pressed into service with the promise of freedom, and have reportedly been used as cannon fodder in some of the most intense fighting in Ukraine. Wagner’s fighters have also been implicated in some of the worst atrocities in the ongoing war.

Who won, and who lost

The US did not have a sound exit strategy in Iraq and so got trapped in a grinding conflict, said Macmillan, adding that Russia has made the same mistake.

Yet the results of the Russian and US invasions have been felt most acutely by the invaded populations — Iraqi society was “shattered” by the US’s “shock and awe” offensive, said Macmillan, while the costs of reconstruction for Ukraine will likely be higher than in Iraq.

Still, there are differences in the consequences that the US faced and that Russia will likely confront for years to come.

While the US was stuck in a quagmire of its own creation for nearly a decade, there were no significant economic hardships experienced by its population. The US economy did not suffer a war-induced shock, it faced no sanctions and diplomatic isolation, and its military was not humiliated in the way Russia’s has been.

Condemnations of US actions were ultimately inconsequential. The US was simply too secure in its role as global hegemon to be treated like a pariah state, and the prospect of an International Criminal Court arrest warrant for Bush or any other senior US government official, as has been issued for Putin, was inconceivable.

For Russia, it is different. Russia is not the Soviet Union — it is a rump state with a struggling economy overly dependent on hydrocarbon exports. Its military, once seen as among the world’s most sophisticated, increasingly looks like a Potemkin army when put to the test.

The consequences for the world at large may also be more severe this time.

War in Ukraine threatens to feed into global insecurity. In Iraq, apart from oil supply instability, the spillover from war was largely contained to the Middle East. Ukraine, on the other hand, is more integrated into the global economy and is a breadbasket that sustains global food markets, while sanctions on Russia have destabilised global energy supplies.

The conflict also comes at a time when the guardrails of an interconnected global order that disincentivised wars between major economies are falling apart. “Globalisation is unwinding,” said Macmillan.

Global attitudes to flashpoint issues like Taiwan are hardening, as the US and China inch towards open conflict — their strategic decisions likely informed in part by every move on the Ukraine chessboard.

The world, in short, is a more dangerous place than it was two decades ago. A major nuclear power is engaged in a war that is sucking in NATO powers. And even superpowers cannot create an alternative reality.