Administrators and striking faculty at the University of Illinois Chicago both reported progress in contract talks that went late Friday. It’s the first note of productive discussions since the strike began on Tuesday.

Administrators cited movement on several issues, including minimum salary increases and the length of the contract. Negotiations are scheduled to resume Sunday afternoon.

On Friday, Javier Reyes, the interim chancellor at the University of Illinois Chicago, vowed to reach an agreement this weekend to end a faculty union strike but said “financial constraints” are preventing the administration from bridging, by his estimate, a gap in proposals of $9.2 million over three years.

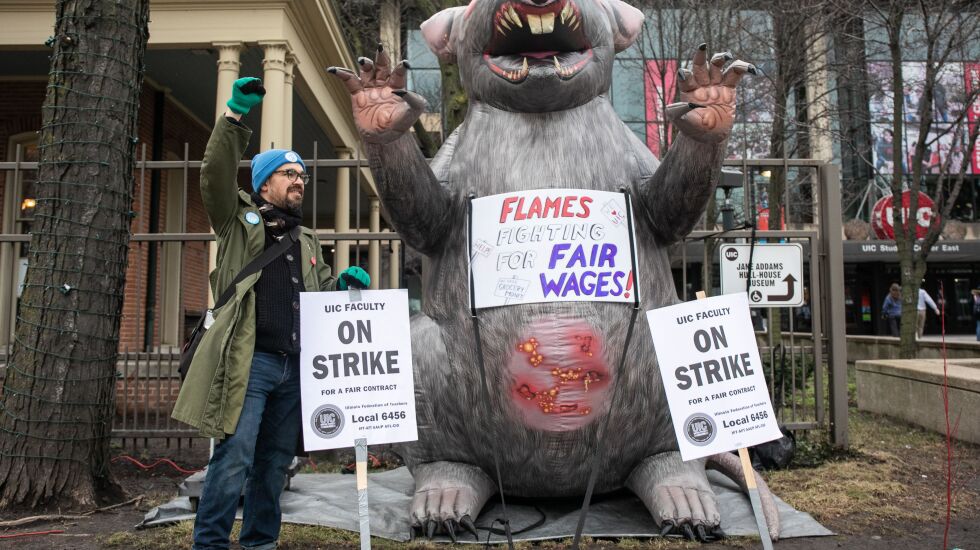

The university administration and UIC United Faculty union returned to the bargaining table Friday afternoon on Day 4 of a work stoppage that has canceled classes and brought newfound attention to the public research university’s Near West Side campus.

A union leader said management made an offer early in Friday’s negotiations that “shows significant enough movement” that bargaining would continue into the evening.

But union members remained on picket lines during the daytime with support from local and state elected officials and some students. The union said it was displeased that negotiations were scheduled in a small room that would not fit members who aren’t on the bargaining committee but wanted to observe. Wednesday’s negotiations featured dozens of observers watching on in a larger space. The two sides did not meet Thursday.

The union and administration remain at odds over minimum salaries for nontenure-track faculty, raises that address inflation for all faculty, mental health support for students and more.

Reyes told the Chicago Sun-Times in an interview Friday that he wants to “figure out the best way to reach a fair, equitable as well as fiscally responsible agreement for our faculty.” But he pointed to economic difficulties that include union proposals that surpass the tuition increase of about 3.6% over the past eight years, he said, and the fact that a little over three-quarters of UIC students don’t pay full tuition.

“We value them and care for them so deeply, as well as every person who works at UIC to fulfill our mission as an institution,” Reyes said of UIC faculty. “But at the same time, we have financial constraints. We have finite resources. We don’t have unlimited amounts of money. We are a state-funded institution.

“Although we have growing enrollment, when you look at the demands our faculty are having for the contract, it’s really hard to meet those demands and really be fiscally responsible for the institution.”

The union responded Friday by noting that a high number of students receiving financial assistance to attend UIC — that is, not paying the full tuition — shouldn’t justify “low, non-competitive wages” for faculty.

“That sentiment too clearly explains the lack of parity between student resources on our campus and others in the system,” said Charitianne Williams, a senior lecturer in the English Department and member of the union bargaining team.

The union has pointed to growing enrollment and subsequent increasing cash reserves as evidence the university has the resources to pass its booming fiscal success along to workers, whose earnings in many cases don’t match impressive credentials.

Nontenure-track current minimum salaries range from $50,000 to $60,500 depending on position and seniority; the union wants the lowest-paid position to receive no less than $61,000. They’re paid lower than tenure-track faculty — whose minimums range from $65,000 to $78,650 — despite oftentimes having similar credentials along with bigger course-loads and class sizes.

The union has publicized a financial statement that shows the university has $1 billion in cash reserves boosted by the increasing enrollment.

The administration has said UIC can’t deplete its reserves by committing cash to a big, indefinite expense such as salaries. And Reyes said that $1 billion figure is outdated and misleading because it includes some restricted funds and is shared money between the University of Illinois’ Chicago, Urbana-Champaign and Springfield campuses. He said the university has “nowhere near” $1 billion in unrestricted funds.

Asked why the Illinois university system doesn’t release campus-level financial statements like counterparts in other states, such as California, Reyes said that would be a question better asked to system- and board-level leaders.

As far as the minimum salaries, Reyes said, “I just don’t think we can only address the numbers at the minimum levels; we have to look at the average of our faculty.

“We do know that our [average] faculty salary for a nine-month appointment is $83,000 for nontenure-track and $134,000 for tenure-track faculty,” Reyes said. “So when you talk about the minimums ... not every faculty is hired at the minimum.

“It’s right now a gap on the economic terms specifically of about $9.2 million over the course of the agreement, three years.”

Union leaders confirmed that figure but questioned how reserves would be depleted if Reyes said higher minimums wouldn’t impact most current faculty members.

“If there are so few people making the minimum it renders it insignificant, why are they fighting so hard? Just bump it up,” said Williams, the bargaining team member.

Reyes has also faced criticism from the faculty union for not being at the bargaining table. The union said Reyes hasn’t attended a bargaining session since May of last year, the two sides’ second meeting. Friday’s session is the 33rd.

Reyes said Friday he wants both sides to stay at the table through the weekend — meeting early mornings and late nights — to reach a deal, calling it his “sincere desire” for classes to resume Monday. But he said, “It’s not my place to take the place at the table when we have a competent labor relations team as well as a competent negotiation team at the union.”

“I am deeply engaged in every step of the process, including with the labor relations team in real time during the negotiations for the purpose of moving forward.” he said.

“But I do also want to mention that I represent the entire campus — our students, our faculty and staff.”

Asked if it was his responsibility at this critical juncture, during a strike, to stabilize the campus and personally step into negotiations, Reyes said, “It continues to be my responsibility to stabilize the campus and to work with both teams. And our provost is at the table, who is the chief academic officer, and is working with the faculty.”

Reyes said he viewed it as his job to “make sure that both parties continue to make movement, and that is my commitment.”

“We are not moving ... away from that table until we reach a resolution,” Reyes said.

The union continued preparing for a longer strike, however, hosting training Friday on civil disobedience. A community organizer shared the pros and cons of disruptive protest tactics, explaining, for example, that occupying university buildings would lead to a more immediate response from administrators than occupying a street corner.

So far the union hasn’t planned any protests beyond outdoor picket lines, Williams said. She said the training was meant to keep members safe in confrontations with police.

“At the beginning of fall semester, we held an informational picket and the police were called,” she said. “I don’t know, necessarily, if we would need to escalate in order to need this information.”

At the outdoor training session, Virginia Costello, another senior lecturer in English, said she and her fellow nontenure-track faculty were still fighting for better pay and more job security.

“Most of my colleagues have a one-year contract, which means they don’t always know until July 15 if they’re going to be hired on Aug. 15, she said. “We’re asking for that to be moved back.”

Undergraduate students also showed up in support of the union. Liz Rathburn, an organizer with Students for a Democratic Society, appreciated the union’s push for more mental health access for students.

“I’ve heard so many students who’ve dropped out because of having some kind of mental health crisis,” they said.

WBEZ’s Char Daston contributed to this story.