President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, fighting for his political life after 20 years as Turkey’s leader ahead of a May election, appears to be leaning on the same political playbook he has for years – that he is the strongman his country needs.

Facing a reinvigorated opposition amid a moment of rare economic calamity – and the aftermath of a once-in-a-lifetime natural disaster – Turkey’s leader is using the same nationalist language that has previously served him so well.

At a rally this week in Ankara that marked the launch of his campaign ahead of 14 May presidential and parliamentary elections, the 69-year-old vowed to confront foreign “imperialists” allegedly seeking to hold back Turkey while making the country a world power as it celebrates its centennial as a modern republic this year, How will he do it? By bringing down inflation while spurring growth.

“We are here to open the door of the Turkish century together with our nation standing up against coup plotters and global imperialists,” he told thousands of supporters of his Justice and Development Party (AKP) at the rally.

Turkey’s president has long been a master of elections. He has rarely lost a vote. He has a strong base of support that almost guarantees him a berth in a 28 May second round of elections should no candidate win a majority on 14 May.

But he has always needed support beyond his base to eventually get himself over the line. Erdogan’s main challenge over the next few weeks is to convince enough undecided and new voters that he can address Turkey’s myriad of problems.

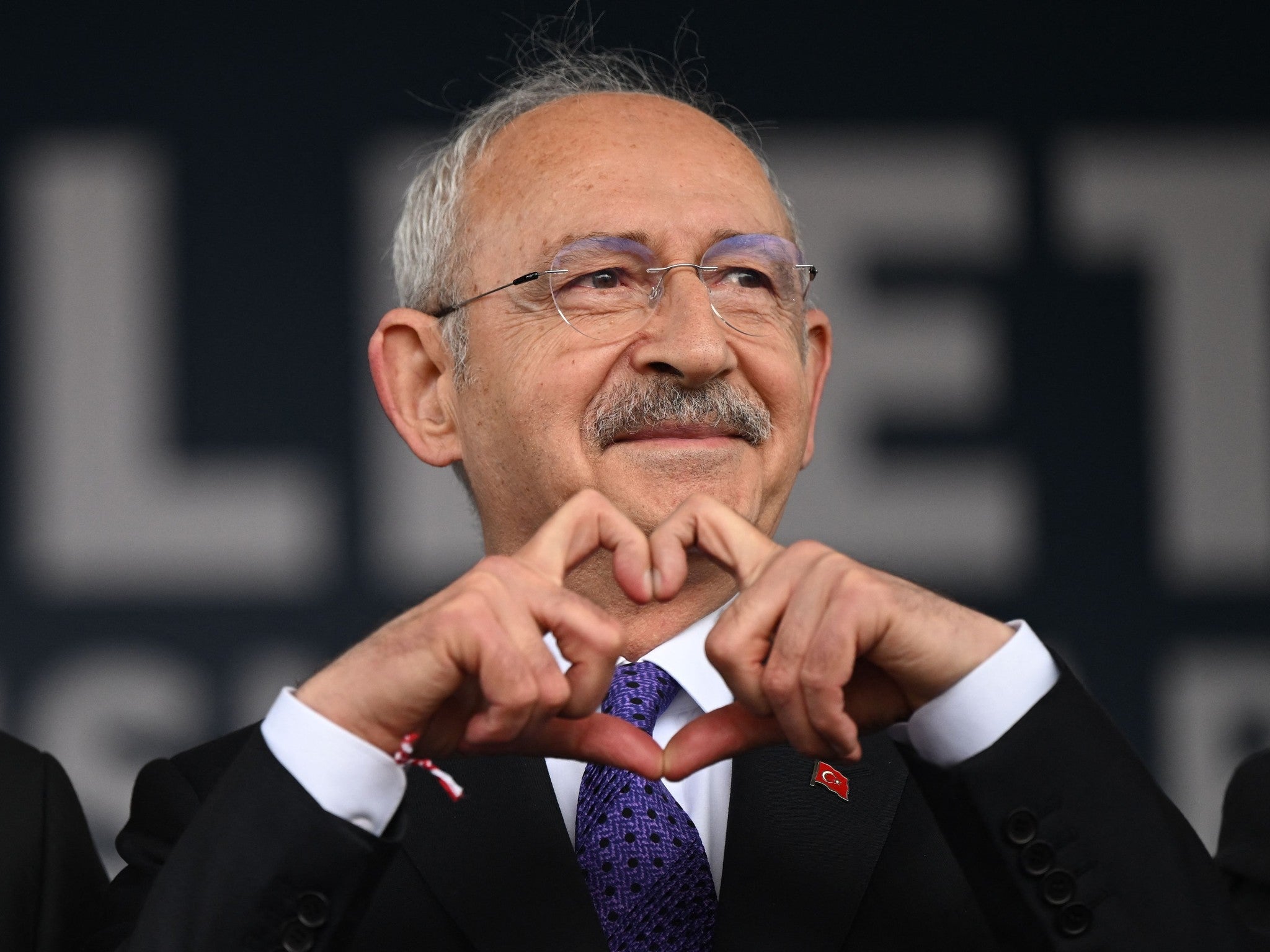

He appears to be faltering at the polls ahead of the vote. His main rival is Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who leads the centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP) – and the pair are locked in a statistical dead heat. In a recent survey from Metropoll, 42.6 per cent of respondents said they would vote for Kilicdaroglu and 41.1 for the president, with the rest for two other candidates or undecided.

Erdogan remains skilled at hitting the same nationalist and populist notes to mobilise AKP supporters. At his rally on Tuesday, he railed against the system. He vowed to change civil service rules to prevent nepotism in hiring at government jobs in an attempt to portray himself as an outsider to a political edifice he has overseen for two decades.

Such talk excites pious, conservative Turks, some of whom are resentful of the perceived privileges of secular Turks. But to win, Erdogan must also win over some other crucial constituencies including: an estimated 6.7 million first-time voters born after 2000; ethnic Kurds divided among several political ideologies; and those in the urban middle class hit hard by inflation and economic malaise. He has struggled to connect to all three groups, particularly the young and Kurds who appear to be leaning strongly in favour of the opposition.

Erdogan also faces the political fallout from of the 6 February earthquakes, in which 50,000 Turks died and millions were displaced. Many fault a badly-botched rescue effort and loose building code enforcement for the high death toll. The disaster stifled Erdogan’s poll numbers and put the entire nation in a grim mood.

“There are increasing signs that he’s doing worse and worse,” says Selim Koru, an analyst at the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey. “The earthquake really set him back significantly. It was a psychological blow. It highlighted the idea that nothing really works as it should in Turkey.”

Erdogan has acknowledged shortcomings in his government’s response to the earthquakes, but has offered a solution that is right out of his old playbook: accelerate development and quickly build 650,000 new housing units. That includes 319,000 homes within a year, he said on Tuesday. Architects, urban planners and geologists have cautioned that building so quickly in a region still recovering from aftershocks is asking for trouble.

Far more than the earthquake response, voters remain focused on the economy. Double and even triple-digit inflation rates have eaten away at savings and purchasing power across the nation. Inflation in February was 55 per cent. The decline in the value of the lira is exacerbated by Erdogan’s insistence on keeping borrowing rates low to stimulate growth.

Experts say the outcome of the vote in May will likely be decided on whether the urban lower middle class and salaried employees will be enraged enough to shift their votes from Erdogan to the opposition.

“The rural parts of the country are fairly Erdoganist; most of the political change is happening in the larger cities, probably on the outskirts,” says Koru. “The swing voters are probably people who are nationalistic. They still think the opposition is borderline treasonous, but they are so devastated by inflation and the economy they will give Kilicdaroglu a chance.”

Erdogan has said repeatedly that he believes high interest rates cause inflation, in defiance of conventional economics. He has vowed to bring inflation down to single digits but has been sending mixed signals on whether he will raise interest rates and implement more orthodox fiscal policies or continue extending cheap credit.

He has claimed that Mehmet Simsek, a former Merrill Lynch economist and former finance minister who oversaw Turkey’s 2000s economic boom, would oversee policy. But Simsek, who abandoned the AKP in 2018, has so far publicly declined to join Erdogan’s team.

Kilicdaroglu, a 74-year-old career politician, also appears to have no grand economic vision. But the six-party opposition coalition he leads includes Ali Babacan, a US-educated former financial consultant who served for a time in Erdogan’s cabinet. The coalition’s Iyi Party has retained former Wharton School finance professor Bilge Yilmaz as its economics guru.

“Around the opposition, there’s this tremendous brain trust of Turkish economists who have an orthodox outlook on the economy who would inspire confidence in economic management,” says Koru. “They would want international funding. They would be interested in inspiring the kind of confidence that Turkey did in the 2000s.”