Of all the questions confronting voters in the 2024 U.S. presidential election, few are as puzzling as the seemingly unwavering support for a political candidate deeply mired in embarrassing sex scandals and criminal business practices.

Such is the case with Donald Trump, whose behavior would have sunk the campaigns of most U.S. presidential candidates.

In the 1980s, for example, Democrat Gary Hart’s presidential ambitions went to ground over allegations of extramarital affairs on a boat aptly named “Monkey Business.” Over the past 20 years, two New York governors, Andrew Cuomo and Eliot Spitzer, both Democrats, resigned over charges of sexual misconduct. Democrat Al Franken’s career in the Senate was scuttled over charges of indiscretions during a USO tour.

But Trump’s convictions of financial fraud and being found culpable for sexual misconduct have not dampened the enthusiasm of supporters of Trump and his “Make America Great Again” movement.

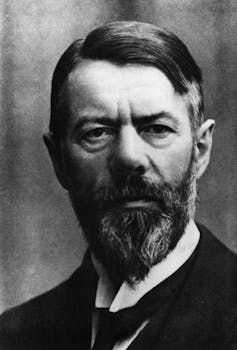

Part of the reason may be explained by Max Weber, an early 20th century German sociologist and social theorist. At the center of Weber’s thinking about political authority was the word “charisma.”

In today’s street lingo, charisma has been shortened to “rizz” and defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “style, charm or attractiveness, and the ability to attract a romantic or sexual partner.”

Nothing could be further from Weber’s understanding of charisma.

The religious roots of charisma

In his “Theory of Social and Economic Organization,” Weber goes back to the Christian roots of the word charisma to describe how social and political power achieved legitimacy within a society.

According to the Greek Bible, Jesus’ followers received spiritual gifts from God. Much later, derived from the Greek word “charis” – meaning “grace, kindness, favor – the word was brought over to English and referred to the gifts of healing, prophecy and other endowments of the Holy Spirit.

For Weber, what makes people charismatic is the possession of such gifts, through which they become mediators between God and their communities.

These gifts of the spirit transform the believer into a prophet.

Weber made a crucial distinction between a priest and a prophet. The priest acquires power through official credentialing and the routine performance of functions such as liturgies and rituals prescribed by the religion.

In contrast with the priest, the prophet derives authority not from official mechanisms but directly from God. The prophet thus stands outside the framework of the official religion – and even beyond society and a political state.

What characterizes the modern-day prophet is his defiance of the regimented order of society and his call to heed a higher calling. The prophet is inherently subversive.

While not religious, as historian Lawrence Rees has pointed out, the political prophet is "quasi-religious,” and the followers of such a person “are looking for more than just lower taxes or better health care, but seek broader, almost spiritual, goals of redemption and salvation.”

‘A call to arms’

Throughout modern history, charismatic leaders have shown their extraordinary ability to elicit devotion to themselves and their causes.

Some have been great spiritual leaders – Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, Civil Rights Movement leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela among them.

Others have been a scourge to humans – including Russian leader Josef Stalin, German dictator Adolf Hitler, Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong and cult leader Jim Jones.

Of those charismatic “prophets,” none may have possessed more charisma than Hitler. He was the prototype of a charismatic leader, according to Weber’s definition.

Like the prophets of old, Hitler was an outsider who possessed remarkable gifts of oratory and uncanny good luck. Of his charismatic traits, none was more important than his ability to persuade. One early follower, Kurt Lüdecke, highlighted the power of a Hitler speech in 1922:

“When he spoke of Germany’s disgrace I felt ready to spring on an enemy. His appeal to German manhood was like a call to arms, the gospel he preached a sacred truth. He seemed another (Martin) Luther. I forgot everything but the man. Glancing around, I saw that his magnetism was holding these thousands as one.”

In his “Inside the Third Reich,” Albert Speer confessed that his decision to join Hitler’s movement was emotional rather than intellectual: “In retrospect, I often have the feeling that something swooped me up off the ground at the time, wrenched me from all my roots, and beamed a host of alien forces upon me.”

Speer was later convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Trump’s charisma

Weber’s concept of charisma helps us understand Trump’s appeal to his Christian followers.

Trump portrays himself as an outsider who will attack the decadent mainstream system – and his followers are willing to fight and die for him.

Indeed, the Jan. 6, 2021, rioters risked their freedom, their careers and, in at least one case, their lives for their leader. One of them, Ashli Babbitt, was fatally shot climbing through a shattered glass door inside the U.S. Capitol.

The list of lives and careers who were imprisoned as a result of service to Trump includes former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort, ex-Trump “fixer” Michael Cohen and former Trump adviser Steve Bannon, among others.

Meanwhile, several ex-Trump lawyers have suffered or are facing disbarment and, in some cases, criminal charges related to their work for the Trump administration.

It’s my belief that Trump is not just an ordinary politician – people think he is a spiritual leader offering to bring them to the promised land.

Right-wing evangelicals such as Paula White, Tony Perkins and Hank Kunneman praise him as a man fulfilling God’s will through his actions.

Social media is filled with images of Trump being supported by Jesus, or even of Trump being crucified like Jesus.

And Trump himself has said that divine intervention saved him from an assassin’s bullets.

“And I’d like to think that God thinks that I’m going to straighten out our country,” Trump told Fox News host Mark Levin in September 2024. “Our country is so sick, and it’s so broken. Our country is just broken.”

A critical flaw

But the Achilles’ heel of the charismatic leader is lack of success.

In the case of Hitler, his battlefield failures in Dunkirk and Stalingrad during World War II punctured the charismatic balloon. But rebellions against his authority were fruitless, and Hitler was able to command obedience until his suicide in April 1945.

The need for continuous success is a cautionary tale for Trump, whose charisma appears to be ebbing.

Trump’s reputation as a winner took a blow with his loss to Joe Biden in the 2020 election. With Biden’s decision to drop out of the race, Vice President Kamala Harris has made the 2024 presidential campaign a much closer race.

If the erosion continues, Trump will likely confront the fates of all failed prophets – to be barred access to the levers of power they crave.

Michael Scott Bryant does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.