After it happened, I’d walk in slow circles outside the house looking for her, my feet hardening and my skin turning a deep red.

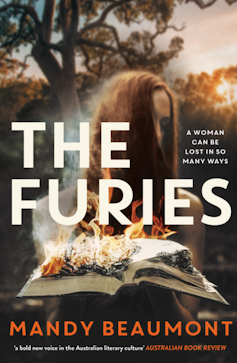

So begins The Furies, the work of debut novelist Mandy Beaumont.

We are propelled forward, desperate to know what “it” might have been. What is this event that leaves Cynthia, a 16-year-old in rural Queensland, to fend for herself in deeply unyielding worlds?

As we plunge further into the novel, we are moved between the past and the present, between what Cynthia knows for sure and what she struggles to remember. Her home is surrounded by the event, surrounded by the hostile bushland. Her missing sister Mallory beckons to her wherever she goes.

Review: The Furies - Mandy Beaumont (Hachette)

Numbly, Cynthia gets a job in the local abattoir, turning to the violent work her father resorted to when his own dreams of the future were warped by the dry reality of the land and a sullen withholding sky. The same numbness is present as Cynthia moves in with Simon, becomes pregnant and loses her baby girl.

We follow helplessly as Cynthia moves from one kind of violence and trauma to the next. She decides to return to the family home, the place where “it” happened, in an attempt to make sense of her past, to mourn her absent sister, and to make plans for the future. She lurches forwards and back in equal measure, devastated by loss.

The Furies shares much with the writing of Barbara Baynton, who characterised the bush as fearsome and masculine, entwining both qualities into one hostile entity. Beaumont’s prose is beautiful and lyrical. The landscape intrudes and menaces throughout: “the river systems … now empty and moaning for rain” and the land itself “a culprit”.

The writing is interesting, because it is so disconnected and imagistic. Sentences are left incomplete, beckoning to things which cannot be articulated. We are swept away by the lyrical; it is hard to get a firm footing on time and action. Cynthia is haunted by her family, changed by the abattoir and by the landscape:

I am sour smell. I am last night’s dinner. I am hard-metal recollection.

The words are an angry howl and we move with this forceful breath. Yet there were times in the novel when I wanted the narrative to relent – for attention to zoom in, closer to the central characters. I also wanted more history and more specifics.

Women’s lives destroyed

The Furies of the title are a chorus of women who have had their lives destroyed by men’s violence, whose voices rise up as Cynthia reads her mother’s letter, left for her in the family home. The sound of the Furies twinned with the wail of Mallory sets off the action of the novel, creating the chasm that Cynthia must fill or fall into. She spends most of the book teetering on the brink.

The novel is most incisive when it comes to issue of class. The tragedy of Cynthia’s family is that her parents lacked the resources to help them navigate life with a sick child. As Cynthia’s mother writes of Mallory and her noise:

It’s like that noise had a life of its own after it left her mouth. Like it was crawling over the chairs and sitting on top of us. Like she was trying to drown us in her sound.

The novel does not provide specific details about Mallory and her condition. There are many kinds of neurodiversity in children, and as a reader I wanted to know more. Suffice to say, Mallory did not get the attention she desperately needed, from either her parents or anyone else. Cynthia, a child herself, was left to care for Mallory, more or less on her own.

As white, working-class people in outback Queensland, Cynthia and Mallory’s parents are unable to cope. Doctors are consulted too late. Relationships are past saving. Cynthia’s parents lock themselves into separate spheres and the wheels of fate turn for their children.

The insularity of Cynthia’s family is evident when Cynthia encounters anyone considered to be “other” in the novel’s rural setting. Her Vietnamese co-workers – Maggie, Kim and Thuy – remain shadowy figures, as does the Greek community in the town. “I haven’t seen so many Greek people in one place before,” Cynthia muses.

The outsider status given to Maggie, Kim and Thuy is a stark reminder that the settler colonialism of the outback remains more hostile to some people than to others.

Violence and ambivalence

The particulars of the family’s pain are folded into a larger narrative about women and the things that mute them in contemporary society.

Trapped in the house, ever more estranged from her increasingly absent husband, Cynthia’s mother recedes into herself and the voices of all the women in pain barge in, indistinguishable from the noise of her small daughter. She tries to shut out the noise as she descends into madness.

That she is left to deal with her children alone is the part of the book that made me most angry. Cynthia’s father is not responsible for Mallory’s violent fate. His hands are clean. Yet, his absences in the book are undoubtedly a catalyst. It is Cynthia’s father, more than her mother, more than the men at the abattoir or the perpetrators of the heinous crimes, who emboldens the Furies and sets everything in motion.

While men’s violence is easy to acknowledge, their ambivalence and lack of care is more insidious. The violence and ambivalence feel inseparable to me, part of a larger societal consciousness that allows men to dismiss women, their anxieties, and eventually their pain and humanity.

The Furies is unapologetically feminist in its preoccupations. It addresses some of the structural inequalities that women still face in contemporary society. The further Cynthia moves from the tragedy of her family, the more clearly she is able to see this.

The realisation allows Cynthia to stop directing her anger at herself. It allows her to start directing the anger outwards at a culture that enables, if not encourages disregard and violence towards women.

The Furies asks a lot of its readers. Cynthia’s voice is that of a traumatised person, who flails in pain and seethes in anger. The stream-of-consciousness narration has a dizzying effect, drawing us in so that we see what Cynthia sees and feel what she feels. The Furies is a devastating book, but one which hints at the possibility of redemption and reckoning.

Natalie Kon-yu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.