Author and journalist Samrat Choudhury’s third book comes at the time Manipur is front and centre of the national conversation. The current fault lines between hill and valley, ethnic loyalties that transcend borders inherited from the colonial state, attacks and reprisals are all a bequest of what he says are larger historical issues that have remained unresolved. Northeast India — A Political History is a “simple, readable, popular history” of the region that maps its long journey from isolation to integration. Edited excerpts.

How difficult is it to write the political history of a region where most chronicles, barring a few exceptions such as the Ahom buranjis and Cheitharon Kumpapa, the Manipuri royal chronicles, are of recent vintage?

Basically there were only those few princely states or kingdoms in the valleys which had written histories going back a long way. Other than that, in the hills there were a lot of cultures that were oral cultures until the arrival of the British. One can rely on the colonial records to get the story from, say, the late 1800s or thereabouts, certainly not much before the Treaty of Yandabo following the Anglo-Burmese War of 1824-26. That’s about far back as it goes.

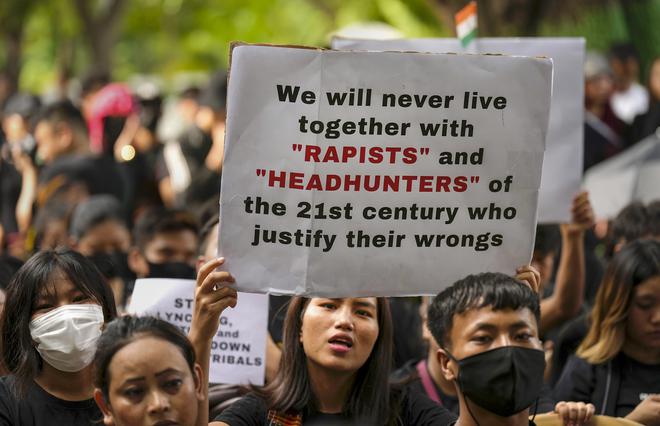

The chapter on Manipur ends on a rather prescient note: Manipur remains suspended in an uneasy peace, prone to descending into fraternal conflict just as it was a thousand years ago, in the days when clan warred against clan and tribe against tribe. Is there a viable resolution road map from the current abyss?

Well, my chapter was written long before any of this happened. Even then one could sense that the larger issues were not resolved, remained dormant, and where we are now, some of them have become active issues. The unresolved issues relate to plains or demands for some kind of autonomy, or sometimes an independent state or country. And those issues are now at the heart of what has happened. Because the different communities are either very strongly for or against the whole issue of separate administration and it is something which has happened before as well and it has been an issue that has held off the conclusion of the Naga peace talks. Now we have the same issue which is at the forefront of the demand among the Kukis. The positions of the Meiteis and the Kukis, or for that matter even the position of the Meiteis vis-a-vis the Kukis and the Nagas — because it is a three-way territorial issue — I don’t see how it can be resolved without some amount of flexibility and creative problem-solving.

The Nehruvian state dangled less carrot and more stick to bring Nagaland and Manipur into its fold after Independence. Do you see the takeover as fair or were the circumstances built into the logic of unifying India?

We have to acknowledge that the basic task of nation-building, building a country out of 562-odd princely states plus a chunk of British India, was a Herculean effort and it involved a lot of use of force in several places, including various parts of Northeast India. There was action elsewhere as well, for instance police action in Hyderabad. But in the case of Northeast, it was different from the beginning partly because of its geographical position. Both carrot and stick were used. The real battles for independence by communities were fought then, what happened subsequently is much milder in comparison. The situation then was still fluid, there were still genuine hopes that they could get their own countries. Now I don’t think that is the situation anymore. Now it is more a case of political benefits that one can get within the Indian Union. The issues are largely settled.

What do you make of the rapid adoption of Christianity in several of the north-eastern States? The process only began around the 1840s... what explains the almost en masse embrace of a distinctively new faith?

I don’t know how or to what one would ascribe the quick pick-up of Christianity in some of the hills. Mizoram offers some clue, because this was one of the places where Christianity made rapid progress. There were a lot of British administrators who were actually against the entry of the missions right from the beginning. One of the colonial administrators who was an eyewitness to the whole process has left some records rather critical of the Church which give us an indication of what was happening. The odd thing was that the missionaries went in as agents of change. The colonial administration was the force of continuity in that society because they wanted to rule through the existing chiefs. They were on the side of the existing social order. In the case of the Lushai Hills [present-day Mizoram], they supported the chiefs whereas the missionaries brought in education, people started getting jobs, the economy changed and the situation changed. The Church became the pathway to development and progress for the individual and given the lack of other opportunities, became attractive in more than one way because it brought immediate material benefits as well.

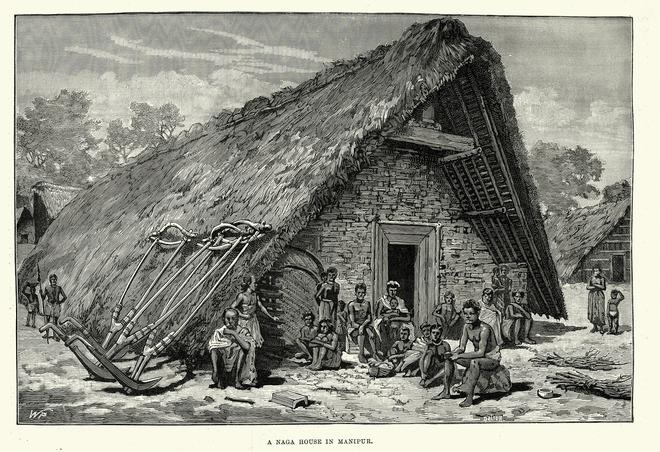

The Company Raj abolished slavery in its territories in 1843, but it remained a sticking point with several of the frontier territories. You mention that tribal chieftains used to sell slaves to agents from Bengal. We know some bit about head-hunting, but how thriving was the slave trade?

I have looked at some of the colonial accounts where they mention emancipating slaves from different areas. One gets a sense of the numbers, fairly substantial going by the population of those places. Slavery did exist in several of the tribal societies and in fact if you read [anthropologist and tribal activist] Verrier Elwin’s writing about his philosophy for NEFA [North East Frontier Agency, present-day Arunachal Pradesh] in the 1950s, he’s still writing about slavery post-Independence. The character of the slavery, the way it was practised was perhaps different from that in the West or other societies, but it did exist and was fairly widespread and a trade went on across the oceans from the Arakan coast and involved Arakanese and Portuguese pirates and perhaps also the Dutch. There is mention, for example, of the exchange rate of slaves — two guns of a certain manufacture for a four-and-a-half-feet-tall male.

You conclude that the political integration of the Northeast into India that started with the 1826 Treaty of Yandaboo is now substantially complete — not only administratively but mentally. But can an iron-clad imagining of India strike root in the liminal borderlands of the Northeast?

When one sees the articulation of what people are talking about now, one doesn’t see so many demands for independence. In fact, it’s quite striking that even with so much that’s happening in Manipur, none of the groups has actually anything against the Central government. For example, the Kuki party [Kuki People’s Alliance] which has belatedly withdrawn from N. Biren Singh’s government has not gone out of the National Democratic Alliance. The rhetoric is to stick with India and wave the Indian flag and say that we are Indian. Largely the mental integration does seem to have happened. But then again, in the historical frame, this is a fairly recent process. If the peace in the entire wider region comes unstuck, then it becomes hard to predict where things will go. The dreams of Nagalim still exist, the dreams of a Kuki-Mizo-Zo country are still around, but people have made their peace.

Northeast India: A Political History; Samrat Choudhury, HarperCollins, ₹699.

abdus.salam@thehindu.co.in