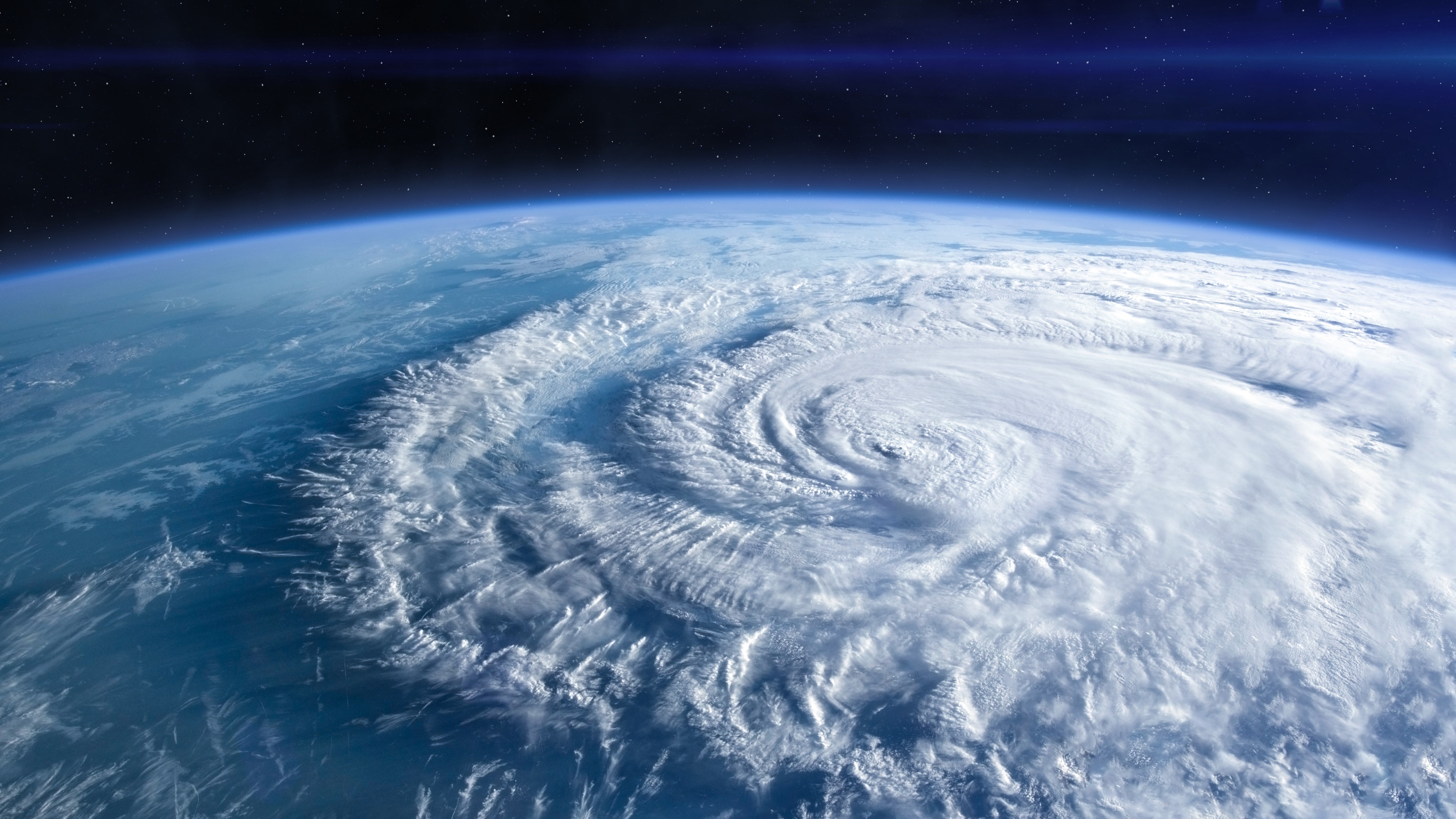

More than two dozen hurricanes could be on their way this year, thanks to climate change and La Niña, experts have forecast.

Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have made their highest-ever May forecast for an Atlantic hurricane season: 17 to 25 named storms. According to the forecast, 13 of these storms will be hurricanes, with winds of 74 mph (119 km/h) or higher, and four to seven will be major hurricanes, with winds of 111 mph (179 km/h) or higher.

"This season is looking to be extraordinary in a number of ways," NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad said at a news conference on Thursday (May 23). Spinrad noted that 2024 was now on track to be "the seventh consecutive above-normal season."

An average hurricane season has 14 named storms, seven of which are hurricanes and three of which are major hurricanes, according to NOAA. The most active season on record, 2020, had 30 named storms.

Scientists previously discovered that climate change has made extremely active Atlantic hurricane seasons much more likely than they were in the 1980s. This is because, while hotter oceans don't make hurricanes more frequent, they do make them grow more quickly and become more powerful.

Related: How are hurricanes named?

Hurricanes grow from a thin layer of warm ocean water that evaporates and rises to form storm clouds. The warmer the ocean is, the more energy the system gets, pushing the storm-formation process into overdrive and enabling violent storms to rapidly take shape.

Since March 2023, average sea surface temperatures around the world have hit record-shattering highs — indicating that a busy storm season is on the cards.

Scientists also predict that El Niño, which recently ended, will transition to La Niña, its cooler counterpart, by the summer or fall. El Niño is a climate cycle in which waters in the tropical eastern Pacific grow warmer than usual, affecting global weather patterns.

During El Niño, winds in the Atlantic are typically stronger and more stable than usual, acting as a brake on hurricane formation. But if the climate cycle follows predictions and El Niño is replaced by La Niña, it could make for a particularly stormy summer. That's because La Niña weakens trade winds and in turns lessens vertical wind shear, which is what breaks up incipient storms.

So far this decade, five storms have blown at an unprecedented 192 mph (309 km/h) or more, leading scientists to propose a new "Category 6" strength to describe them.