As reported by the Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Sun-Times:

Even before the city’s official founding, Chicago played a major role in the nation’s mail delivery. Military couriers traveled between Fort Dearborn, Fort Wayne in Indiana and Fort Green Bay in Wisconsin as early as 1831, the Encyclopedia of Chicago states. Stagecoach services began in 1836, and as the city grew, so did its role as a major hub for mail deliveries nationwide.

But Chicago’s postal service hasn’t always been fair to all residents in terms of delivery and hiring practices — something the city’s Latino community refused to tolerate in 1978.

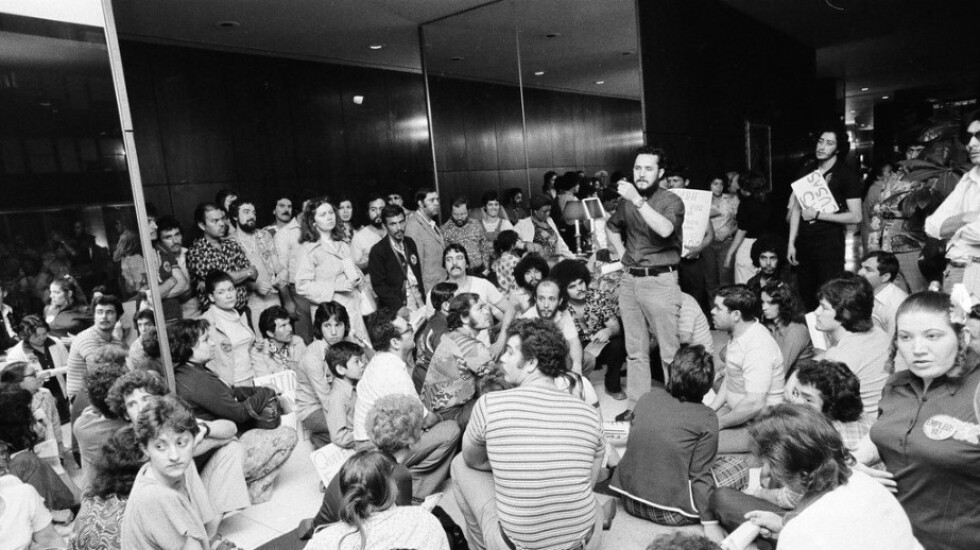

On May 18, 1978, roughly 80 to 100 Latino residents staged a sit-in inside Chicago Postmaster Frank Goldie’s Lake Shore Drive apartment lobby to demand that he hire more Latinos as clerks and mail carriers.

Goldie came to Chicago by way of Toledo, Ohio, according to the July 16, 1977 edition of the Chicago Daily News. He worked as a postmaster there before his promotion to Chicago. His tenure began in August 1977, and the Daily News snapped its first photo of him on Sept. 1 at Midway Airport as he honored the 50th anniversary of the first airmail flight.

At the time, Chicago’s post office faced problems that pre-dated Goldie’s tenure, and it was still in its infancy as the United States Postal Service. Prior to 1966, it was called the United States Post Office Department, and politicians usually appointed postmasters based on patronage, not experience, according to WTTW.

In Chicago, Henry W. McGee’s appointment to the position that same year marked the first time in city history that an actual postal worker with experience (37 years to be exact) held the job. Within his first month on the job, a backlog of mail in the city caused a national crisis that eventually led to the department’s reorganization into the USPS that operates today.

The West Town Coalition, which organized the demonstration, never stated why it targeted the post office specifically, or if it did, the Chicago Sun-Times article about the protest published May 19 failed to mention it. But it’s not hard to see why the community would want more Latino postal employees. The jobs paid well, offered union membership and helped many support a middle-class lifestyle. They may have also wanted more bilingual clerks staffing post offices in Spanish-speaking communities.

The demonstrators at 3150 N. Lake Shore Dr. insisted they meet with Goldie to “press their demands for more postal jobs for Latinos,” the Sun-Times article said. But they ran into a problem: Goldie wasn’t home.

“Police eventually were able to find Goldie and have him talk by phone with leaders of the delegation,” the Chicago Sun-Times reported. Outside, another 40 demonstrators picketed, and another group of protesters at the main Post Office “presented Goldie with 350 applications for an exam to be held soon to fill 1,250 clerk carrier jobs.”

The sit-in lasted about 90 minutes and ended peacefully, the paper said. Goldie agreed to meet with the leaders of the delegation at 10 a.m. the following day at the main Post Office.

The paper never followed up to determine if anything came from the meeting with Goldie. He retired in 1987, and Janet Norfleet took over the role.