Regular readers will know that we're big fans of optical illusions here at Creative Bloq. They regularly leave us baffled and befuddled, but there are scientists out there studying the phenomenon, and one team has just announced a breakthrough in their research into how we perceive such illusions.

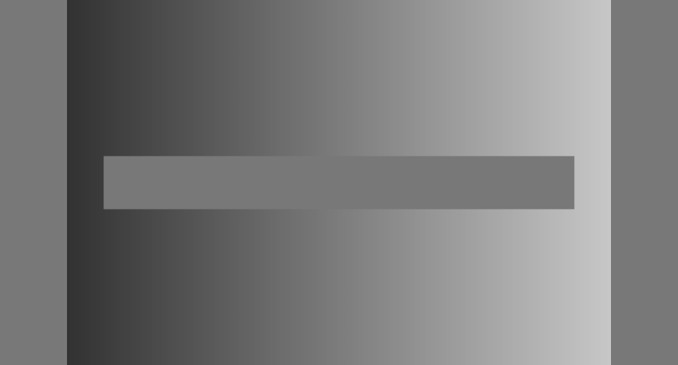

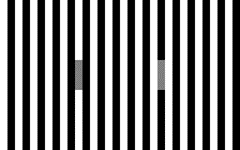

While it's often believed that it's our brain that is responsible for causing optical illusions, scientists from Exeter University have demonstrated that, actually, the limitations of our eyes are more to blame for why we get tricked by illusions like the one below (see our pick of the best optical illusions for more examples).

There's been much debate about whether optical illusions are caused by neural processing in our eyes and low-level visual centres or more complex mental processes involving context and prior knowledge (see the recent Coca-Cola can optical illusion).

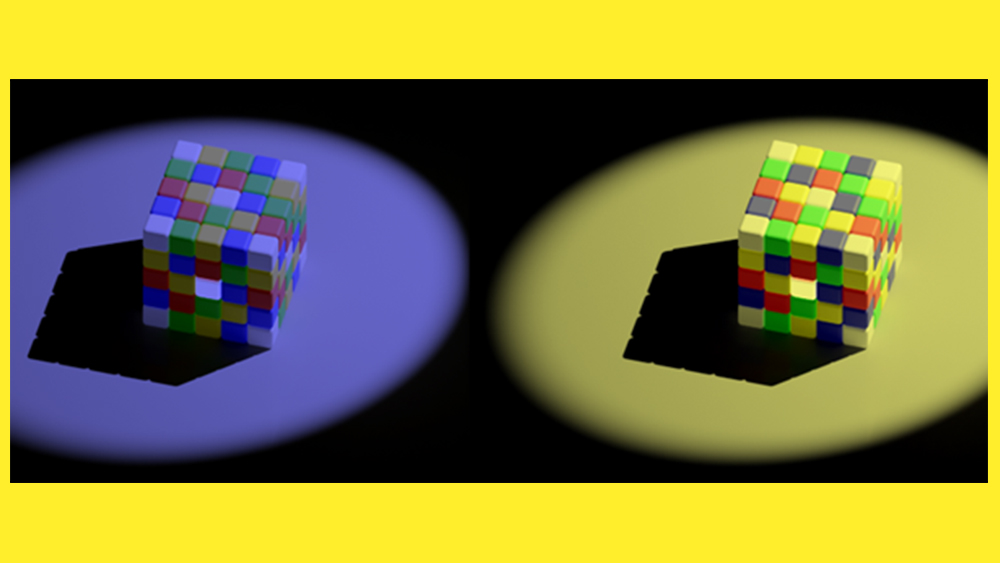

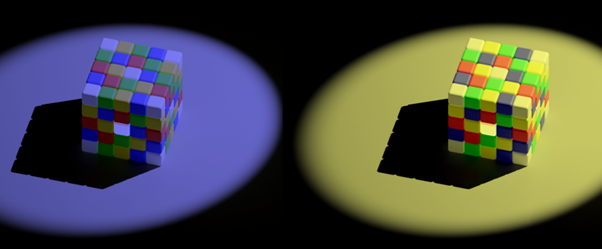

To investigate, Dr Jolyon Troscianko and his team at Exeter University's Centre for Ecology and Conservation examined a range of optical illusions that involve the perception of colour, like the one above. The study found that simple neural responses rather than deeper psychological processes were to blame and they produced a model to predict how optical illusions will be seen.

“Our eyes send messages to the brain by making neurons fire faster or slower,” says Troscianko. “However, there’s a limit to how quickly they can fire, and previous research hasn’t considered how the limit might affect the ways we see colour.” He added that this "throws into the air a lot of long-held assumptions about how visual illusions work."

Intriguingly, Troscianko says the work sheds light on how we see the high-dynamic range in the best televisions, which have areas that are 10,000 times brighter than the darkest black. “How our eyes and brains can handle this contrast is a puzzle," he says "because tests show that the highest contrasts we humans can see at a single spatial scale is around 200:1. Even more confusingly, the neurons connecting our eyes to our brains can only handle contrasts of about 10:1.

“Our model shows how neurons with such limited contrast bandwidth can combine their signals to allow us to see these enormous contrasts, but the information is ‘compressed’ – resulting in visual illusions."

The model shows how different neurons have precisely evolved to use every bit of capacity. For example, some are sensitive to tiny differences in grey levels at medium-sized scales but are overwhelmed by high contrasts. Others are much less sensitive but can work over a wider range of contrasts, giving deep differences in black and white. We're just happy that the optical illusions we love have scientific value as well as being delights to look at (for more, see our pick of the best optical illusions of 2022).