In August 2013, an 8-year-old boy was rushed to the hospital in San Antonio, Texas after contracting a so-called brain-eating amoeba infection. His case was unusual because he ultimately survived: Brain-eating amoeba infections are nearly always fatal.

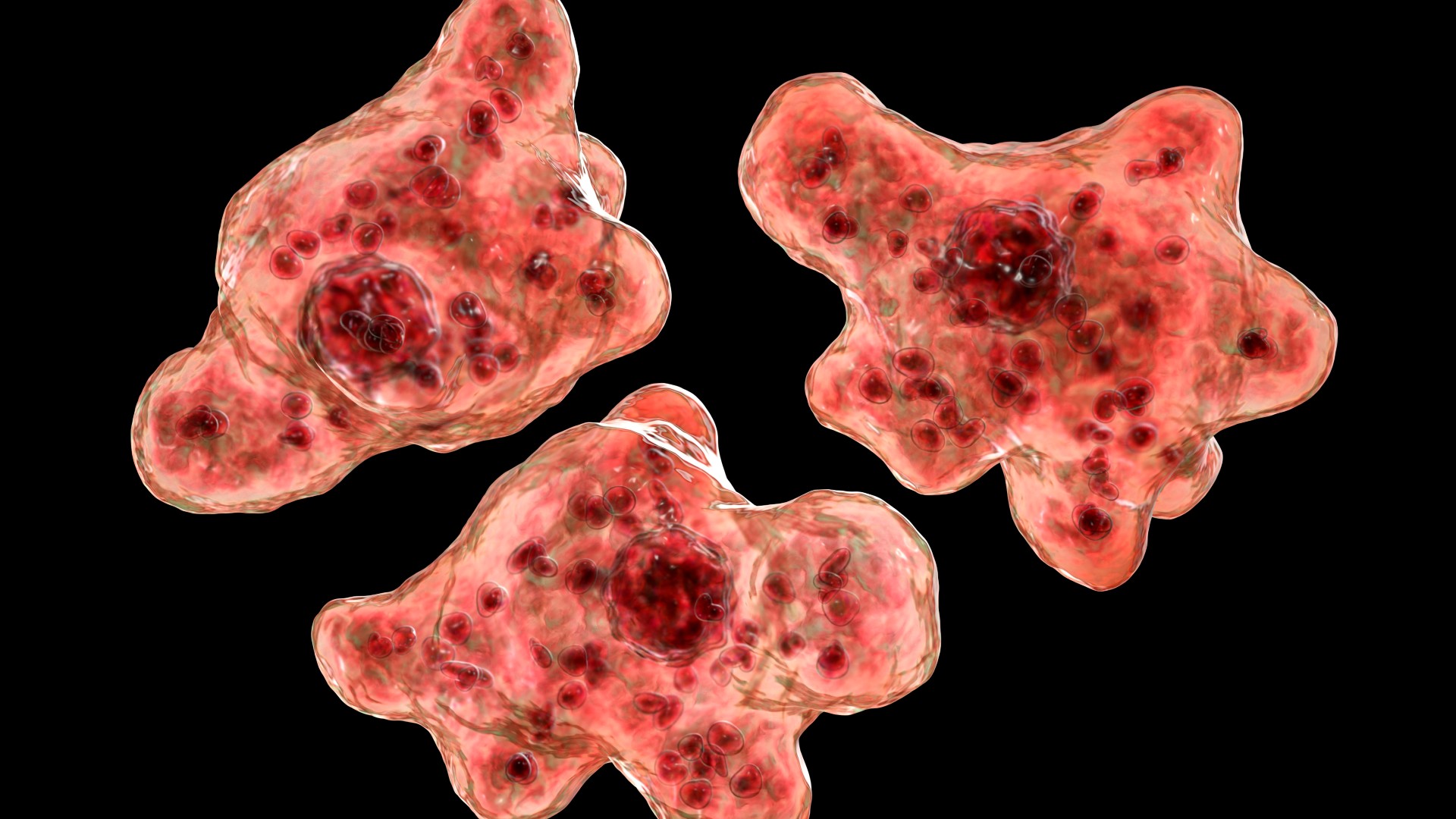

The boy's infection was caused by Naegleria fowleri, a single-celled organism that lives in warm freshwater lakes, rivers and hot springs. The protozoan enters the body when water goes up the nose and into the brain, causing a disease called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis.

Dennis Conrad, a now-retired professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, was one of the doctors who treated the boy in 2013. Live Science spoke with Conrad about what it was like fighting the disease and what lessons can be drawn from the experience.

Related: Deadly amoeba brain infection can result from unsafe nasal rinsing, CDC warns

Emily Cooke: So, taking it back to 2013, what happened to this boy?

Dennis Conrad: This boy had been with his mother for the summer, who lives in Mexico.

Many of those "colonias" that exist on the border do not have potable water: They have no sewerage system, nor pipe water. So, they [people] buy their drinking water from large trucks, but otherwise, the water that they need, not for drinking necessarily, but for laundering and bathing and that, are from a natural source.

This boy liked to go swimming in the tributary of the Rio Grande, and that's where we think he acquired his initial infection, because he would be wading and had contact with that water. The other thing about amoebae is naturally they consume bacteria, including coliform bacteria. So, areas that are contaminated with sewage, where there's a lot of fecal organism overgrowth, are conducive to support the organism. Swimming in the polluted waters of that area probably is why he had a significant exposure to amoeba, which led to his infection.

Related: Rare 'brain-eating' amoeba infection behind death of 2-year-old in Nevada

EC: When he arrived at the hospital, what symptoms did he have?

DC: By the time he arrived, he had a significant reduction in the state of his mental status: He had non-specific responses to certain primitive reflexes, like pain, but he was not really interacting with his environment.

When he initially developed symptoms, which you could argue would be indistinguishable from a viral illness or other illness — fever, headache, generalized malaise, loss of appetite — he was seen in several clinics in Mexico and either given nothing or just given a shot of an antibacterial, and then sent home.

However, as he got worse, he started to show signs of increased intracranial pressure, vomiting, somnolence etc., and eventually it was recognized that he had progressive, severe disease that did not respond to his prior outpatient therapies.

So, he was seen at the border and then referred to San Antonio, because they recognized the severity of his disease. He came in through the emergency room, through University Hospital, and it was recognized that he had signs and symptoms of meningitis. [Meningitis is an infection of the protective membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord].

In the course of looking at some of the cytology [examining cells taken from the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain], somebody thought they saw amoebic forms.

EC: How does the organism cause these symptoms? How might infection lead to meningitis?

DC: Although it's unicellular, it's a complex organism that the body recognizes as not their own, so it provokes an immune inflammatory response.

Probably the primary reason that they [patients] become so overtly symptomatic is the profound host inflammatory response to the organism. In the process of responding to that, there is some inadvertent, or collateral injury to neurons and other central nervous system cells.

As an aside for your understanding, a lot of injury due to meningitis isn't unique to amoeba. We used to see that in the old days of bacterial meningitis like Haemophilus influenzae, where many of the symptoms, especially those that was associated with severe disease, permanent neurologic sequelae, and in some cases, even death, was felt to be more due to the actual host inflammatory response than it was due to the direct effect of the organism.

Related: Fatal 'brain-eating' amoeba successfully treated with repurposed UTI drug

EC: How did you treat this boy?

DC: He was treated with, if you can accept a Yiddish word, a "gemish" of agents. I had previously cared for two boys that had died of amoebic meningitis, so I'd had some experience, and it's like all these generals fighting their last war: I remember what failed and tried to do something.

For the first time, an agent [drug] was potentially available for use called miltefosine. It was early morning hours, I called Atlanta and had the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] release the drug because it was only available for experimental use. So, they flew it in and then we received it, I think [at] about 11 a.m. that morning and was able to begin him on therapy.

However, what I think, quite honestly, contributed to his ultimate survival was relieving his intense intracranial hypertension, which is due to brain swelling, edema. We had the neurosurgeons come in the early morning hours and put in [a] bilateral third ventricle drain — mechanical drainage of the space in the brain called the ventricles — which was a mechanism to relieve pressure.

In the past, the two boys that had died that I had treated ultimately died of complications of cerebral edema, where they eventually herniated, compressing their brainstem and then essentially dying of cardiorespiratory arrest due to brainstem compromise. But, by keeping his pressures down, we prevented that fatal event occurring and allowed the anti-infective cocktail to actually work.

By about 36 hours of treatment, we no longer saw amoebae in the ventricular fluid that we would periodically sample from his drains. You could actually take fluid that had been externally drained and look at it. So, there was some evidence we killed the amoeba.

There was still all that dead protein floating around in his brain, so you still contend, unfortunately, with the inflammatory response. And I think that's where corticosteroids step in. They, to some degree, reduce the edema and therefore somewhat have an anti-inflammatory effect.

EC: I imagine, because this is a very rare infection, that it's quite difficult to recognize. Is this the case?

DC: If you have an index of suspicion, and you're in the right environment, and especially in my case, if you've had experience with the disease, I would think you can come to the diagnosis fairly quickly.

EC: How long did it take the boy to recover? How long was he in the hospital for?

DC: Once he left critical care, I lost contact with him because I was a consultant. However, I believe he stayed approximately three weeks in hospital. After that, he had to get continuing care in a skilled nursing unit and then have some rehabilitation, because he never fully recovered all his function. He survived, but because of the injury that occurred prior to initiation of therapy, it was not completely reversible. Because of the inflammatory effects, he was pretty profoundly affected.

Related: 'Brain-eating' amoeba ruled out in 'cluster of illnesses' in Oklahoma. What could the cause be?

EC: What general advice would you give to parents who might be concerned about these kinds of infections?

DC: Avoidance is probably the best. Interestingly, chlorination of water is adequate to kill amoeba. I think a minimal threshold of 10 parts per million of free chlorine is adequate, so if they just swim in chlorinated water, this is something they don't have to be concerned about.

'Brain-eating' amoeba infections are nearly always fatal. But could new treatments change that?

Read more:

—Can you get a brain-eating amoeba from tap water?

—'Brain-eating' infections could become more common, scientists warn

As well, swimming in salt water is good because the organism cannot tolerate high salt concentrations. So, typical sea water does not support the growth of amoeba. If you look at where they've been reported in the U.S., this is classically in southern, warm states: Florida, Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana, up to Oklahoma, with Arkansas actually having the majority of cases and it really doesn't exist above that. If you do swim in water sources where there's a potential exposure, then avoid diving, or ideally submerging your head, because it's the mechanical force of water up into the nostrils that actually floods the cribriform plate [part of the bone that forms the roof of the nasal cavity] that allows the organism to then migrate into the brain.

Finally, take heed. If there's warnings not to swim because the coliform content is too high, which is basically a food truck for the amoeba, don't go in there.

The last thing is fast-moving water. Amoebae like water that is stagnant with a lot of vegetative matter, such as leaves and that, which supports the bacteria, which in turn supports the amoeba. So if you jump in a fast-moving stream, or swim, like [if you] go to Colorado and swim in a rapid, you don't have to worry because you're not really going to get exposed there. So basically, it's about prevention, ideally by avoidance. If you do potentially expose yourself, just realize where the risks are greater.

To put it in perspective, there's less than 10 cases per year on average in the United States so it's a rare disease. There's other things parents need to worry about that are more likely to happen.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.