Despite how it sounds, a psychobiotic diet has nothing to do with Alfred Hitchcock or what Patrick Bateman eats. The term, popularized by neuroscientist John Cryan at the University College Cork in the early 2010s, refers to a diet that focuses on eating fermented and prebiotic foods to support both gut and mental health.

There’s evidence in animals and humans that a diet rich in both fermented and prebiotic (grub that has a ton of fiber in it) foods supports gut health, which in turn sustains mental health. The connection between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract, held together by a network of nerves and receptors, is known as the gut-brain axis.

A study published last month in the journal Molecular Psychiatry provides additional evidence for the benefits of a psychobiotic diet. Researchers found that prebiotic and fermented foods support mental wellness.

LONGEVITY HACKS is a regular series from Inverse on the science-backed strategies to live better, healthier, and longer without medicine. Get more in our Hacks index.

Science in action — For four weeks, 45 adults randomly assigned to one of two groups ate either a diet chock full of prebiotic and fermented foods or ate as normal. Participants were healthy but ate diets low in fiber. For instance, their typical diets usually included less than 15 grams of fiber, when 30 grams of fiber per day is recommended.

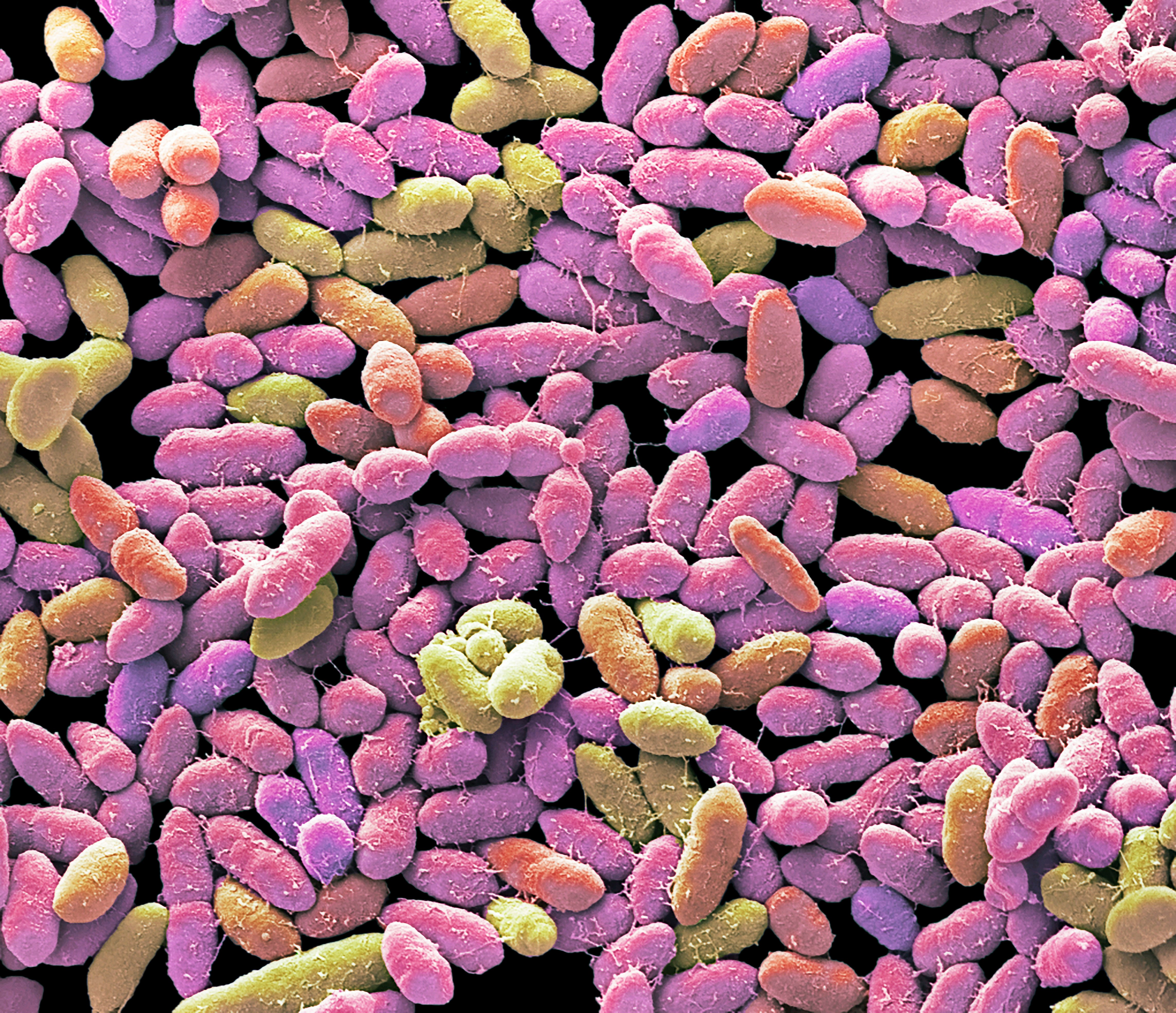

In addition to filling out questionnaires about perceived stress, participants also gave blood, urine, and stool samples for analysis. The researchers performed what’s known as shotgun sequencing, in which they randomly chopped up genomic sequences found in the stool and let a computer piece them back together, showing a full portrait of the bacteria that came from the gut.

The psychobiotic group showed five new types of bacteria, according to lead author Kirsten Berding, a nutrition scientist who completed this work for her Ph.D. at University College Cork. She now works in the baby formula industry. What’s more, the psychobiotic group reported better sleep and lower stress levels. Berding also says their fat metabolites changed, indicating that their body was consuming and processing less fat.

“Specific microbes can, through different routes, regulate how you feel, how you think — like your memory [or] your social behaviors,” Berding tells Inverse.

Why it’s a hack — Think of feeding your gut the way you might feed an aquarium. Teeming with life, the gut needs a special diet in order to flourish.

Fiber is a form of carbohydrate that our digestive systems can’t break down. However, when they reach our colons, the billions of bacteria that live there feed on those fibrous foods that we left behind, and allow them to thrive.

That’s why eating a prebiotic diet is key to maintaining good gut health, because they allow good bacteria to flourish. It's also one reason why a diet high in processed sugar is deemed unhealthy. Many processed foods contain little or no fiber to nourish diverse bacteria in the gut, so the microbiome loses strength and diversity. Onions, leeks, cabbage, apples, bananas, and oats all make the prebiotic list, as do most whole plant-based foods.

Similarly, fermented foods, like kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, and kombucha, foster gut diversity. They’re made using controlled microbial growth in which live microbes, like yeast, feed on natural sugars in food and convert it into a new, flavorful compound, such as alcohol. Fermented foods populate the gut with live organisms that promote balance.

What about beer? Berding says it may have gut benefits in small amounts, but “like other alcohol, is not that beneficial to the microbiome.”

One main highway connecting the gut and brain is the vagus nerve (which is actually more than one nerve). This part of the parasympathetic nervous system controls involuntary processes like digestion and breathing. As such, it has nerve outposts in the brain, heart, and gut so they can communicate. Gut diversity and health can improve communication and digestion in this system. Another gut-brain connector is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates stress in the body.

Different types of bacteria communicate using these different highways, Berding says, so the more bacteria, the better communication is between the brain and gut. The paper details that while researchers are still parsing biological mechanisms behind the effects of the psychobiotic diet, a strong indicator of its goodness comes from anti-inflammatory properties.

How it affects longevity — The gut is the proverbial backbone of so many of the body’s systems. Not only is it connected to the brain, but it’s also linked to the immune system.

As we age, there’s evidence that our gut microbiome becomes less diverse. This decrease stems from many potential causes. For one, as we get older, we can’t comfortably eat as many fiber-rich foods, sometimes because we don’t have the dentition to chow down on them. Fermented and prebiotic foods can help support diversity as we age better than, say, a predominantly fast-food diet could.

Researchers have investigated populations that maintain a healthy gut as they age. A thriving gut microbiome is also associated with improved cognition and immune health. However, this remains a chicken-egg question: Does maintaining a healthy gut stave off the effects of aging, or do actions meant to slow the effects aging also boost the gut?

While Berding says this research leaves her with more questions than answers, it’s certain that the psychobiotic diet promotes foods that are healthy in myriad other ways. As gut researchers continue to firm up evidence for this unique gut-brain diet, adding fiber and fermented foods will still do lots of good.

Hack score out of 10 — 🍎🍌🧅🥗🍎🍌🧅🥗 (8/10 psychobiotic foods)