If you ask people in dry regions what they value most, water usually comes first. It is basic and expensive at the same time. Yet scarcity is no longer limited to deserts. Population growth, old pipes and uneven access are reshaping how water is experienced in cities across the world. The World Bank estimates that by 2050, more than a billion people will live in urban areas without enough reliable water. Supply is not expanding to meet that demand. In this setting, Latin America occupies an unusual place. A large share of the planet’s renewable freshwater is found in South America. Brazil, Colombia and Peru all rank among the countries with the most water. The figures suggest security, but daily life tells a more complicated story.

Brazil holds the world’s largest freshwater reserve, accounting for about 12% of global supplyBrazil is cited as holding around 12% of the world’s freshwater, according to Instituto Terra. Rivers, wetlands and rain-driven systems support forests, farms and cities. Water also underpins energy production and transport. Much of it, however, is far from where most people live. The southeast, where population and industry are concentrated, relies on basins under growing stress. Pollution, land clearing and overuse have slowly reduced resilience. Abundance exists, but not evenly.

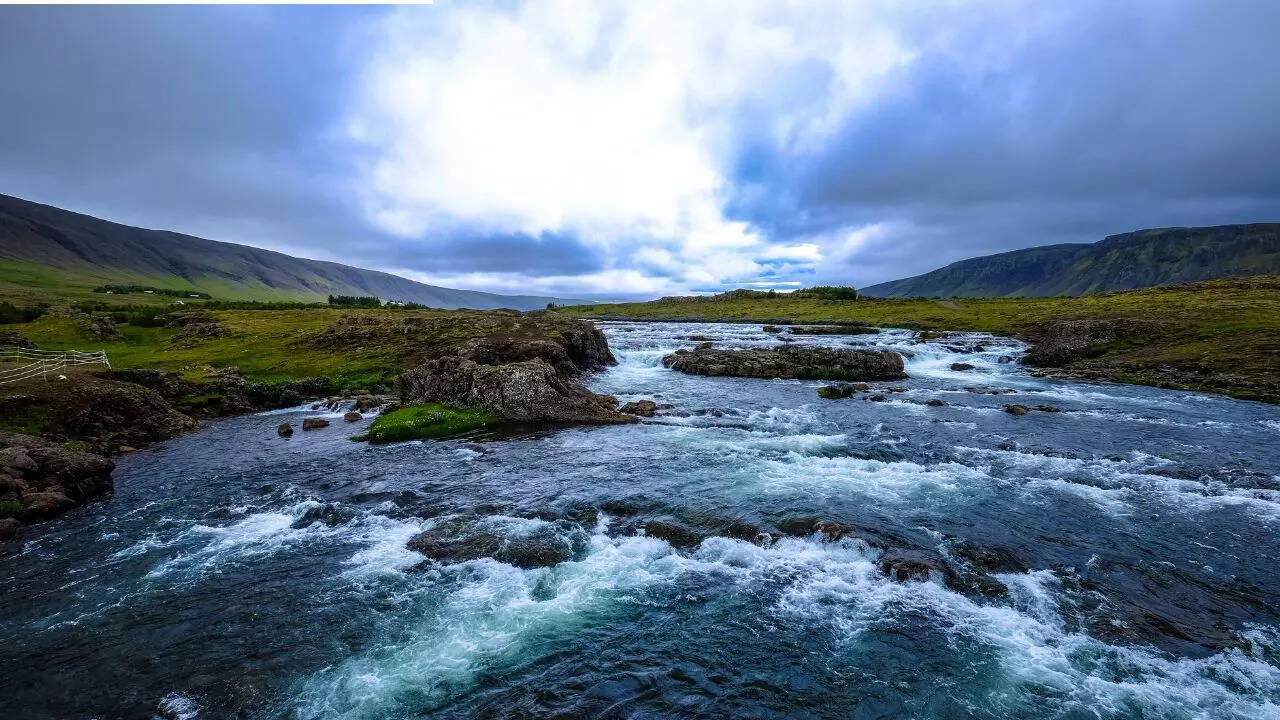

Colombia’s rivers flow from the Andes through regions of heavy rainfall. Peru’s water is tied closely to mountains, glaciers and seasonal melt. On paper, both countries are well supplied. In practice, access depends on geography and infrastructure. Glaciers are retreating. Rainfall patterns are less predictable. What once felt stable now feels exposed.

According to Blue Water Intelligence, these are the top 10 countries with the highest freshwater reserves as of 2024:

- Brazil

- Russia

- Canada

- United States

- Indonesia

- China

- Colombia

- Peru

- India

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

Urban demand reveals deep inequality

Cities show the strain most clearly. In places like Sao Paulo and Lima, water is lost before it reaches the tap. Old pipes leak. Systems are poorly maintained. Wealthier neighbourhoods tend to consume more and waste more. Meanwhile, poorer districts live with rationing and interruptions. Scarcity appears not because water is absent, but because it is unevenly managed.

Brazilian river basins face slow erosion

Some of the pressure is easiest to see in smaller systems. The Doce River Basin is not the largest in Brazil, yet it serves one of the country’s most populated regions. Decades of extraction and land misuse have damaged springs and reduced water quality. Restoration projects now focus on recovering sources rather than expanding supply. Progress is gradual and uneven.

Reuse and treatment quietly shape the future

Only a small fraction of global water is usable. Agriculture consumes most of it. As demand grows, cities draw from more distant and costly sources. Wastewater reuse offers another route, but much of it still flows untreated into rivers across Latin America. New treatment plants and small-scale reuse projects exist, often unnoticed. They do not resolve the problem. They simply slow its advance, buying time in a region long assumed to be safe.