Bernie Marsden, the much-loved former Whitesnake guitarist and solo artist, died a year ago at the age of 72. Responding on Twitter, David Coverdale referred to his “old friend” as “a genuinely funny and gifted man, whom I was honoured to know and share a stage with”.

Marsden’s publicist had broken the sad news on behalf of the guitarist’s family, revealing: “Bernie died peacefully on Thursday evening [August 24] with his wife, Fran, and daughters, Charlotte and Olivia, by his side.” It added: “Bernie never lost his passion for music, writing and recording new songs until the end.”

Marsden may have been best known as a member of Whitesnake, the band he co-founded with singer Coverdale and guitarist Micky Moody in 1978, but he spent a lifetime in rock’n’roll, playing with Wild Turkey, Cozy Powell’s Hammer, UFO, Babe Ruth, Paice Ashton & Lord, MGM, Alaska, Company Of Snakes, The Moody-Marsden Band and more.

Born into a working-class family in Buckinghamshire on May 7, 1951, Bernard John Marsden began playing music with a second-hand Spanish guitar. He saved his pocket money for an electric instrument, and started out in the local club scene in the late 1960s, inspired, like so many others, by the boom in blues music.

“I loved Hank Marvin in The Shadows as a kid,” he told Classic Rock in 2020. “But Eric Clapton was the first guitar player I really adored, because I was old enough to relate to it. George Harrison comes into this as well, and then it was Peter Green. I saw Fleetwood Mac on so many occasions.”

On one memorable occasion, Marsden helped the Fleetwood Mac roadies load in the gear and took a seat in the corner of the room.

“Somebody must have told Peter that I’d helped out, so he came over and said: ‘You look like you could do with a beer.’ Then he sat down and chatted,” Marsden recalled. “It was such a great moment.”

Having formed his first real group, Skinny Cat, at 17, Marsden’s first pro gig was as a successor for Mick Bolton in UFO in 1972, but lasted for just for some live gigs and a couple of demos. The arrangement wasn’t a great fit in musical or personality terms, and it all ended in on-stage fisticuffs at a gig in London when, responding to a slap in the face from Phil Mogg, Marsden whacked the singer between the shoulder blades with his guitar. Exit Bernie Marsden, enter Michael Schenker.

The following year Bernie resurfaced with former Jethro Tull bassist Glenn Cornick’s next band, Wild Turkey. In early 1974, charismatic drummer Cozy Powell was fresh out of the Jeff Beck Group with his Mickie Most-produced instrumental single Dance With The Devil rocketing up the chart, when out of the blue Bernie got a call from him.

“I had first met Cozy when I was in Wild Turkey, and a fortnight later he called me to ask what I was doing on Wednesday,” Marsden told Classic Rock in 1999. “When I replied ‘nothing’, I got: ‘Okay, be at the BBC, ten o’clock, Top Of The Pops. Ta-ra’, and he was gone.”

Although brief, Bernie’s spell alongside Powell introduced him to keyboard player Don Airey (now with Deep Purple).

“I came from the jazz world, and had never worked with a rock band before,” Airey recalls now. “Bernie had just bought one of Eric Clapton’s Les Pauls for five hundred pounds, and the sounds he got were a revelation to me. Plus, Bernie saved my life following a collision on the M1 at seventy miles an hour. The door of the van flew open, and I was headed out until Bernie grabbed me and hauled me back in. Had he not done so, I doubt I’d have survived.”

“I loved Bernie’s playing,” says bassist Neil Murray, his bandmate in Whitesnake. “He had such an attitude, and could be aggressive, though he was sensitive when required. He played from the heart.”

In 1975 Bernie replaced guitarist Alan Shacklock in Babe Ruth, and played on their albums Stealin’ Home and Kid’s Stuff. Things took another turn when Powell recommended his former bandmate in Cozy Powell’s Hammer to the ex-Deep Purple pair of Jon Lord and Ian Paice, who were forming a group with Ashton, Gardner & Dyke frontman/keyboard player Tony Ashton. Paice recalls Bernie blowing the other auditionees out of the studio door.

“Bernie was a class above everyone else,” says Paice. “We had some technical whizz kids there, but they had no feel, also people with no feel but lots of skill. So when he walked in the door he was a breath of fresh air.”

Then came the band with whom Marsden will always be most associated. While in Munich recording the follow-up to Paice Ashton Lord’s 1977 album Malice In Wonderland, Marsden met David Coverdale for the first time. Not long after, he joined David Coverdale’s White Snake, as they were called originally.

In fact, in a classic conundrum, Marsden found himself fretting over two mouth-watering gigs at once when PAL saxophonist Howie Casey put his name forward to Paul McCartney’s Wings, to replace Jimmy McCulloch, although as it turned out no offer was made.

“The Paice Ashton Lord album is very controlled and slick, there’s no great blowing in it, it’s about the songs and arrangements,” Marsden told Classic Rock. “So when I started playing freely at rehearsal, David took me aside and said: ‘Erm, can I have a word? I had no idea you played like that’. That’s how it began.”

Besides Coverdale’s commanding vocal presence, the partnership between Marsden and slide guitarist Micky Moody was at the heart of Whitesnake’s greatness, and the band built their reputation on stage, their music a dizzying mix of commercial hard rock and dirty blues, overlaid with the type of sexual innuendo that these days would be completely unacceptable.

It was Marsden who proposed Whitesnake should add some soul by covering Bobby Bland’s R&B ballad Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City, which became a highlight of their live set, the connection between band and audience often bringing Coverdale to tears. Marsden spoke of an “instant rapport” with his “surrogate brother” Coverdale. “Neither of us had any brothers or sisters, we were born in the same year, and although we grew up two hundred miles apart we discovered we had the same influences.”

Marsden had co-written Whitesnake’s two biggest hits, Fool For Your Loving and Here I Go Again, but that didn’t prevent Coverdale from firing Marsden, Murray and Paice upon completion of the band’s fifth album, 1982’s Saints & Sinners, as he set his sights on the US market and the new MTV. “It wasn’t personal, just business,” Coverdale explained ofthe sackings. “They were cruising on gold status, and I’m hungry for platinum.”

The re-recording of Fool For Your Loving and Here I Go Again by later incarnations of Whitesnake during their rise to MTV domination poured salt into the wound. The royalty cheques were very welcome, of course, and Bernie once told me that he considered the updated Here I Go Again “excellent”, although he didn’t have the same feeling about the version of Fool For Your Loving by a line-up featuring guitar virtuoso Steve Vai.

“Micky and I saw the video together at a gig in Spain,” he said with a smirk. “Steve is a fantastic player, but when he fell to his knees and began praying to that guitar, Micky collapsed to his own knees and began crying with laughter. It was terrible, dreadful. They ruined it.”

At the time he was ousted from Whitesnake, Marsden was still a young man, and his future troubled him. “I was thinking: ‘I’m thirty years old, I’m finished,’” he said. He needn’t have worried. A wide array of bands, projects and solo records followed. Some were more successful than others, but he was tenacious. “That’s the thing about Bernie,” Don Airey says. “When faced by a wall, he went around it. He never gave up.”

The short-lived band SOS was followed by two albums from Alaska, a group that deserved better. When Deep Purple confirmed a comeback at Knebworth Park in 1985, Bernie used his connection with Ian Paice to blag a spot for Alaska as openers on the bill.

After Alaska came MGM, which reunited him with Murray and former Trapeze guitarist Mel Galley, who had succeeded him in Whitesnake.

As the decade ended, Bernie formed the Moody-Marsden Band with Micky Moody, the first of several bands to celebrate his heritage in Whitesnake.

As the Company Of Snakes, Marsden and Moody were reunited with Murray and Airey. In 2001 I wrote an ‘on the road’ piece at a club show in Wrexham for Classic Rock. Despite preparing to release their debut album, Burst The Bubble, the band’s repertoire was still stuffed with ’Snake standards. “In an ideal world I’d eventually like to get to the point where the set is fifty per cent, or even sixty-forty, original material,” he told me.

Although Marsden spoke of Coverdale with caution, he thought he would actually approve of the Company Of Snakes: “In his heart of hearts, I think he’d do so most highly. After all, he’d be watching his own show.”

At that gig, when Bernie went to the bar, Airey confided that every time Marsden’s phone rang he still expected Coverdale to be at the other end. Returning with the drinks, Bernie said with a smile: “If David did call, I’d ask him where and when he wanted to meet. Only a fool or a liar would say otherwise.”

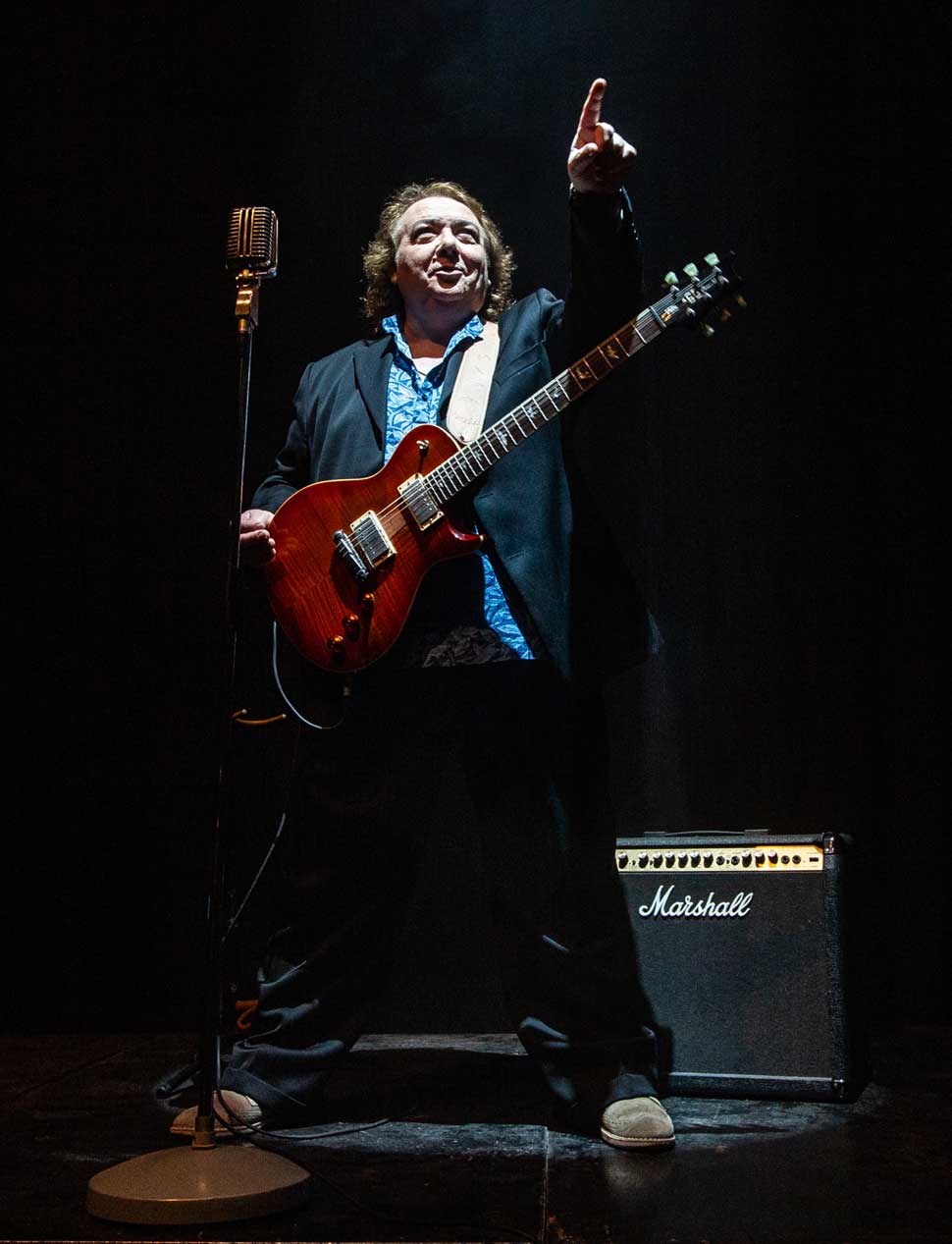

In 2010 Marsden and Coverdale began exchanging emails, and then ran into one another at an airport. That meeting led to the guitarist guesting with Whitesnake at the Sweden Rock Festival the following year. A few weeks later it happened again at Hammersmith.

Marsden described those experiences as “fantastic”, but, having fallen out with Micky Moody he was quick to nip in the bud any possibility of a classic Whitesnake reunion, commenting: “That particular bridge has been torn down.”

“Bernie was very happy to be reconciled with David,” Don Airey believes. “It closed the book for him.”

“Bernie and Micky had such great, fun-loving personalities, which is why it was a shame they fell out so badly,” Neil Murray comments. “Put the two of them together and all sorts of lunacy happened. They loved practical jokes, from pretending to be ghosts when Whitesnake recorded at the [supposedly haunted] Clearwell Castle, to hiring a pantomime horse costume for an important record company presentation.”

“Bernie had no ‘off’ button and was always a barrel of laughs, especially with Micky,” says Ian Paice. “They were a source of great amusement – sometimes annoyingly, but they provided a lot of fun.”

Murray, Airey and Paice all remained in regular contact with Marsden, although due to covid and their own schedules they saw less of him than they would have liked. Each of them knew that Bernie was ill, but not the full extent of his condition.

For Joe Bonamassa, the first inkling that something was wrong came when Marsden declined what had become a regular jam session at Bonamassa’s show.

“Bernie would always get to the gigs early, because he wanted to tell stories before he sat in with us,” Bonamasa explains sadly. “Bernie knew everyone, and he had the best stories, but he was so modest.”

Having met for the first time at Bonamassa’s Royal Albert Hall show in 2009, the pair collaborated on Bonamassa’s next album, Royal Tea, and they became firm friends.

“I am truly heartbroken,” Bonamassa said. “There has been no better ambassador for the electric guitar than Bernie Marsden. The guy had such tone, he could play through anything. Bernie was a great singer, too, though he didn’t get full credit for that.”

“Regardless of what he was plugged into, Bernie always had the best sound on stage,” says FM guitarist Jim Kirkpatrick, who for almost 20 years accompanied Marsden at hundreds of solo shows, as well as writing and recording. “It could be some cheap rubbish amp and guitar, but he’d make it sound great. He was an incredibly funny and witty man. He would have me howling at his tales.”

In adulthood, Marsden felt privileged to become a friend of his boyhood hero Peter Green. In fact, he spent the day of Green’s all-star tribute show at the London Palladium with Green “talking about Robert Johnson, guitars and fishing”. With amusement in his voice, Marsden spoke of reminding Green what was going on and offered to drive him to the Palladium, “and he just said: ‘Nah, a cup of tea with you would be just as good.’”

Ian Paice continued to play what he calls “extracurricular gigs” with Marsden on an occasional basis. “If I use the word ‘hustler’ about Bernie it’s in the nicest possible sense,” he says with a smile. “The guy was always looking for something to do, and he totally believed in himself. The songs he wrote justify that.”

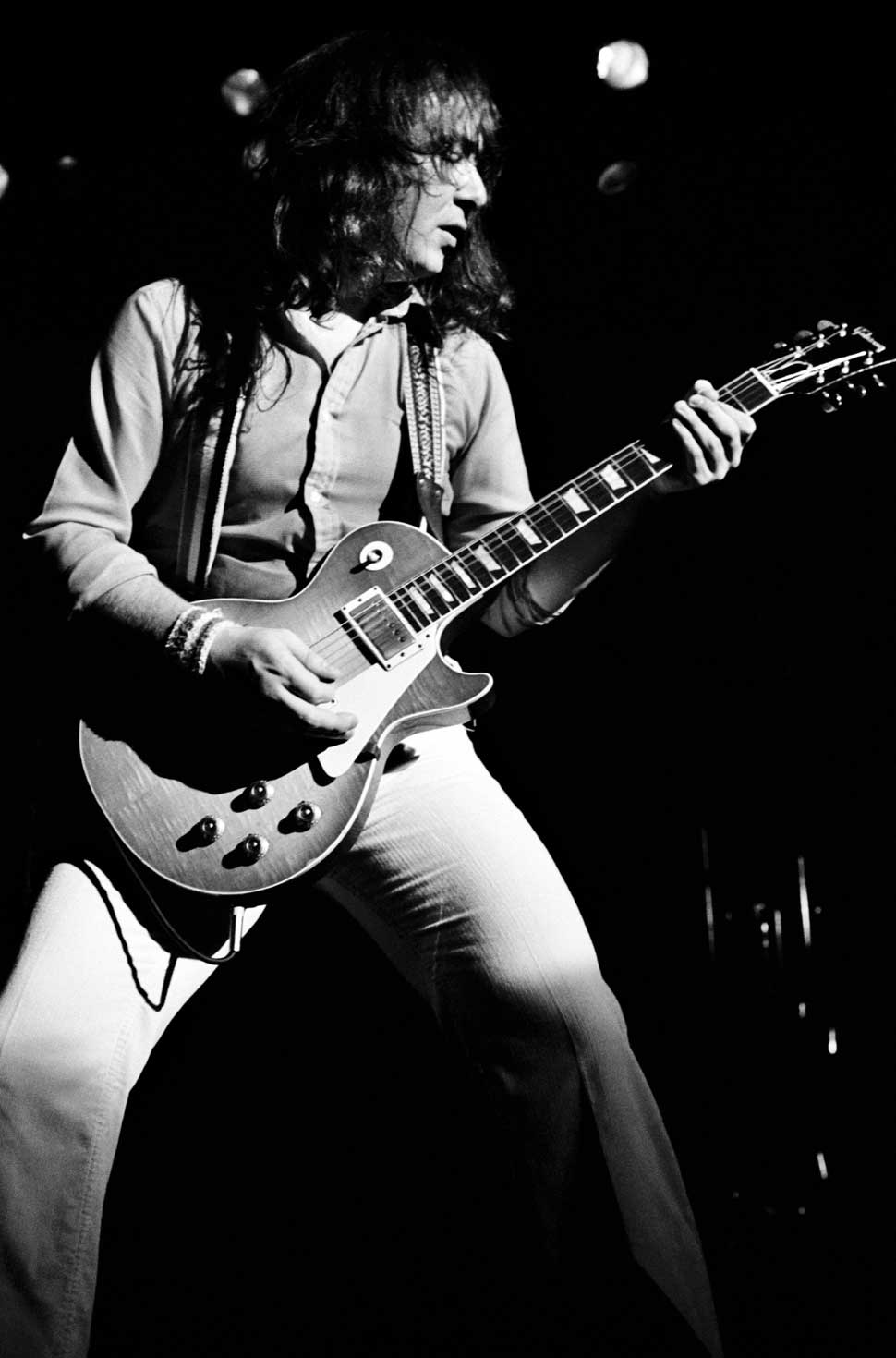

Don Airey last saw Marsden a couple of years ago, when Bernie appeared as a guest at the keyboard player’s local charity gig in Great Gransden. “Bernie turned up with The Beast [his celebrated 1959 Gibson Les Paul, nicknamed by Cozy Powell] and played this absolutely incredible blues set,” Airey says, marvelling at the memory. “It was one of the greatest half-hours of guitar playing that I’ve ever seen.”

During his final years Marsden’s work rate never slipped, and three acclaimed post-pandemic solo albums – Kings, Chess and Trios – paid tribute to the music that he’d grown up with.

“If you’ve got the talent, luck will fall your way,” Bernie once told Classic Rock. “All I’ve ever tried to do is play a show with as much honesty as I can, because without the people who put their hands in their pockets and come to gigs there’s nothing left.”