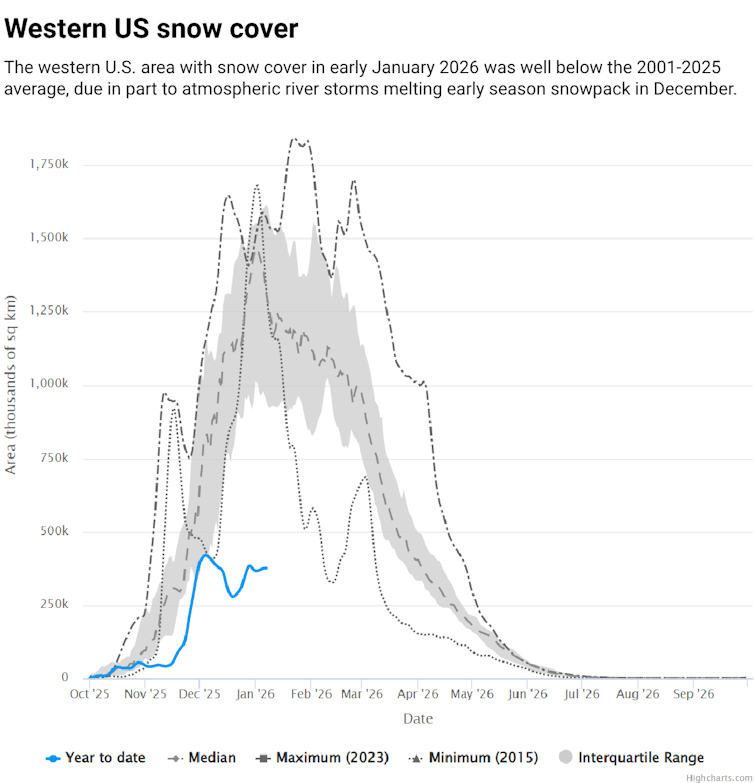

Much of the western U.S. has started 2026 in the midst of a snow drought. That might sound surprising, given the record precipitation from atmospheric rivers hitting the region in recent weeks, but those storms were actually part of the problem.

To understand this year’s snow drought – and why conditions like this are a growing concern for western water supplies – let’s look at what a snow drought is and what happened when atmospheric river storms arrived in December.

What is a snow drought?

Typically, hydrologists like me measure the snowpack by the amount of water it contains. When the snowpack’s water content is low compared with historical conditions, you’re looking at a snow drought.

A snow drought can delayed ski slope opening dates and cause poor early winter recreation conditions.

It can also create water supply problems the following summer. The West’s mountain snowpack has historically been a dependable natural reservoir of water, providing fresh water to downstream farms, orchards and cities as it slowly melts. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that up to 75% of the region’s annual water supply depends on snowmelt.

Snow drought is different from other types of drought because its defining characteristic is lack of water in a specific form – snow – but not necessarily the lack of water, per se. A region can be in a snow drought during times of normal or even above-normal precipitation if temperatures are warm enough that precipitation falls as rain when snow would normally be expected.

This form of snow drought – known as a warm snow drought – is becoming more prevalent as the climate warms, and it’s what parts of the West have been seeing so far this winter.

How an atmospheric river worsened the snow drought

Washington state saw the risks in early December 2025 when a major atmospheric river storm dumped record precipitation in parts of the Pacific Northwest. Up to 24 inches fell in the Cascade Mountains between Dec. 1 and Dec. 15. The Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at Scripps Oceanographic Institute documented reports of flooding, landslides and damage to several highways that could take months to repair. Five stream gauges in the region reached record flood levels, and 16 others exceeded “major flood” status.

Yet, the storm paradoxically left the region’s water supplies worse off in its wake.

The reason was the double-whammy nature of the event: a large, mostly rainstorm occurring against the backdrop of an uncharacteristically warm autumn across the western U.S.

Atmospheric rivers act like a conveyor belt, carrying water from warm, tropical regions. The December storm and the region’s warm temperatures conspired to produce a large rainfall event, with snow mostly limited to areas above 9,000 feet in elevation, according to data from the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes.

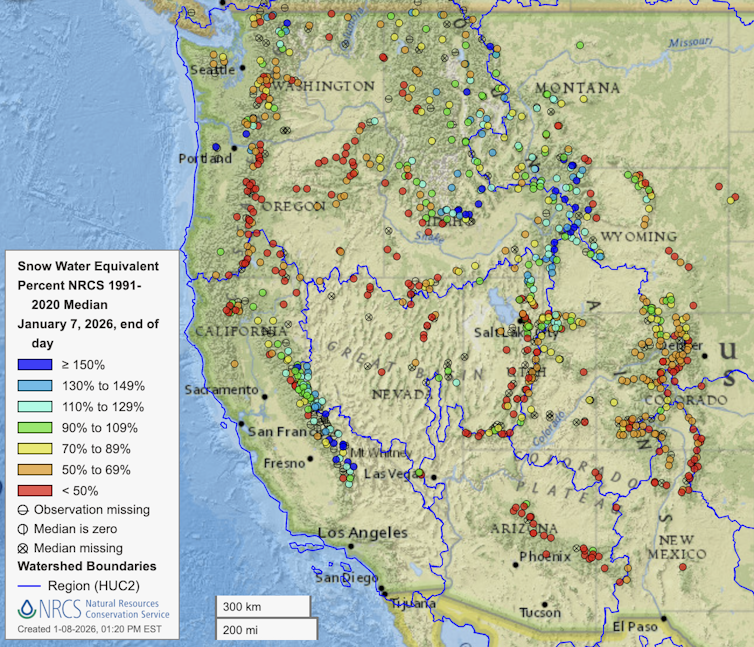

The rainfall melted a significant amount of snow in mountain watersheds, which contributed to the flooding in Washington state. The melting also decreased the amount of water stored in the snowpack by about 50% in the Yakima River Basin over the course of that event.

As global temperatures rise, forecasters expect to see more precipitation falling as rain in the late fall and early spring rather than snow compared with the past. This rain can melt existing snow, contributing to snow drought as well as flooding and landslides.

What’s ahead

Fortunately, it’s still early in the 2026 winter season. The West’s major snow accumulation months are generally from now until March, and the western snowpack could recover.

More snow has since fallen in the Yakima River Basin, which has made up the snow water storage it lost during the December storm, although it was still well below historical norms in early January 2026.

Scientists and water resource managers are working on ways to better predict snow drought and its effects several weeks to months ahead. Researchers are also seeking to better understand how individual storms produce rain and snow so that we can improve snowpack forecasting – a theme of recent work by my research group.

As temperatures warm and snow droughts become more common, this research will be essential to help water resources managers, winter sports industries and everyone else who relies on snow to prepare for the future.

Alejandro N. Flores receives funding from the National Science Foundation, US Department of Energy, NASA, USDA Agricultural Research Service, and Henry's Fork Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.