The sprawling banyan tree of Vachathi and the now-defunct well, some metres away, had borne witness that late afternoon on June 20, 1992, when a joint force of the Forest-, Police- and the Revenue Deparments descended on the Malayali tribal village at the foothills of Sitheri Hills in Harur in Dharmapuri district, in an ostensible “crackdown on sandalwood logging”. The raid left in its wake, a trail of gendered violence, with the rape of 18 tribal girls and the pillage of a village.

The events of June 20, 1992 and their aftermath in Vachathi, would set in motion a three -decade long battle for justice for the women and the village, one that would culminate in the conviction of 215 personnel of Forest-, Revenue- and Police Departments, who had participated in the raid.

On September 29, 2023, when Justice P. Velmurugan read the 78 page verdict upholding the 2011 trial court verdict convicting 215 men of the Forest-, Revenue- and Police Departments of rape and pillage in Vachathi, it threw two issues into the limelight, by denying them: the impunity enjoyed by the State apparatus under the cover of official duty and the patriarchal diktat of the rape survivors’ silence and shame.

Blanket immunity claimed under the guise of ‘official duty’ is not absolute, and rape and pillage do not constitute official duty, said the court. The survivors’ account that documented the layers of gendered violence exposed the stretch of that immunity that the accused persons had claimed, while hoping for the silence of the survivors of sexual assault, particularly because they were from marginalised communities.

June 20, 1992

“There were sudden wails in the village that swarmed with vehicles from all sides; the forest men in khakhi entered homes, threw and kicked things, dragged us by the hair, picked up people from the fields, beat and dragged women grazing livestock to the banyan tree,” says Rani, who was 13 years old and in class 8 at the time of the incident. She, along with her then 17-year-old sister, was dragged from a shack in their uncle’s field to the banyan tree, where the entire village of women and children were huddled in fear. “The men had fled to the nearby Sitheri Hills thinking the women would not be harmed,” says Rani.

“They (forest personnel) scanned the crowd and summoned us young girls. They made us climb onto the lorry and drove off saying they needed us to find the hidden sandalwood. They took us to the lakeside and raped us,” says Lalitha, a survivor, who was 15 then. “When I was brought back, I didn’t know the other girls too, had been raped. We all kept silent.” The whole village was then taken to the Harur forest office, grouped into three groups of 30 women, and about 15 of the men who had remained. “There, they gave us a broomstick and forced us to beat our Oor Gownder Perumal (village head), and asked him, as we hit him, if this was how he protected his village,” says Lalitha.

Also Read: Victory for the weak: On justice and the Vachathi verdict

“The village head was my maternal uncle. We all cried and refused to hit him, but when we refused, they hit us with the same broomstick,” explains Rani, crying as she spoke about the events from three decades ago, recalling the horror and paralysis the village felt at this violent emasculation of their head.

At the Harur forest office that night, the young girls unaware that others too had been raped, huddled in a corner with their families. “I did not go out to relieve myself, fearing I would be dragged and raped again,” said Lalitha.

In Vachathi, the resident’s livestock was slaughtered and the cooked meals were brought to the Harur forest office the next day. “They physically destroyed us, and in front of us, they sat and ate our rice and our livestock. They made us eat the bones and leftovers from their leaves,” recounts Lalitha

The following night the residents were produced before the Harur magistrate. The women were handcuffed in pairs and walked on the Harur main road to the magistrate, with everyone watching. “We live by the forests, and had never been humiliated this way before,” says Lalitha, her eyes welling up from the memory, so many years later. “The magistrate didn’t ask us a single thing, even after seeing so many of us all so dishevelled, and we were warned against speaking about the torture inflicted upon us”.

Punitive rape as collective punishment

The violence that unfolded in Vachathi blurred the lines between a mob and the State. It adhered to the playbook of targeted gendered violence, where the men were emasculated and women were reminded that their bodies were sites of violence, as a form of collective punishment.

“At times I feel like I suffered for the sake of our village. Our whole village suffered,” says Rani, the youngest rape survivor. The collective experience of violence had also, in a way, benumbed her individual experience of punitive rape. This was the case with all the rape survivors, who wanted to foreground the collective pain of the village.

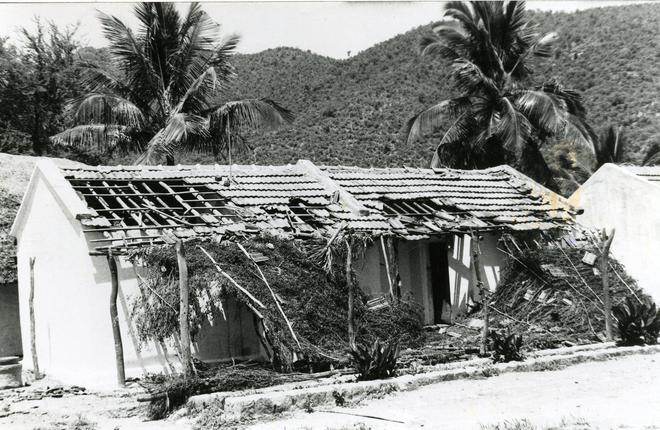

“When we were taken to the jail, one forest officer said, “Go bear your children in jail,” said Rani. “In the weeks after, when we came back to the village from jail, there were no houses, no food, no water. There was broken glass in our rice, and millets, there was kerosene mixed in with our food,” she says. After Lalitha returned to the village, she could not find her parents, who were hiding in the Sitheri Hills. “I staggered to the village well feeling very thirsty but it reeked of oil and kerosene with rice and animal intestines floating in the waters,” says Lalitha.

Kala was 16, when she was raped. “When I first started going to the court a decade later to testify, I would carry along my infant daughter on my hip. Over the years, after every court visit, my daughter would ask, when will this all end for our village. Today, all our children have seen it end,” says Kala.

Protection for smugglers

In the days preceding Vachathi raid, four trucks of sandalwood were loaded from Kalasambadi, the hamlet above Vachathi on the Sitheri Hills. “The forest staff, in collusion with the smugglers who had connections in the AIADMK, the then ruling party, had commissioned cutting of the sandalwood engaging the tribals of Kalasambadi as coolies. But there was a discrepancy in the weight of the wood, and about 30 to 60 tonnes of sandalwood went missing. The forest staff came down to Vachathi from Kalasambadi looking for the ‘hidden sandalwood’,” says Dilli Babu, an ex-MLA of Harur from the CPI (M).

“The forest men would come, just pick up some of our village men, ask them to go with them to the hills to cut sandalwood trees for ₹100 as wages. It was the same as us women, being called to pick mangoes for wages,” says Rani, recounting that period.

Justice Velmurugan’s verdict placed on record the rot that ran deep, and to the top, profiting off the backs of the poor. The verdict observed how the complaints of the villagers to the then Collector and Superintendent of Police of the collusion of forest officials with the smugglers, and their use of the tribal poor as coolies were ignored. “Persons named Murugan, Ganesan, Pollachi Ramasamy, and Namakkal Mastan with the help of various range officers Thandapani and Nagarajan had engaged local villagers in cutting, hiding and smuggling of sandalwood….all carried out by “big shots” but innocent tribals were made scapegoats by foisting cases on them,” said the verdict. “There was no evidence to show the forest department filed cases on those named sandalwood smugglers,” it added.

The officials foisted false smuggling cases against the victims only to escape from the offences committed against the victims, the Court observed.

People would collect firewood, and for each head load they had to pay ₹30 to the forest staff in order to be able to take it to Gobinathampatty junction (some 8 km from Vachanthi) to sell it for ₹60, long after the Vachathi incident. Yet they were branded as smugglers – a blemish the Court erased on record last month.

Even before the Madras High Court verdict, during the trial at the Sessions court, Judge Ashok Kumar was stunned, when he heard the testimony of a woman, whose infant wanted water while in custody at the forest office in Harur on the night of June 20 - 21, 1992 and how one of the forest men offered to urinate for the child to drink. She pointed to the man in question, when the judge asked her to. The enraged judge made him stand through all the hearings, recounts Dilli Babu, listing the humiliations heaped on Vachathi’s survivors.

It took a village

The violence of those three days in June 1992 was brought to light by the CPI(M)’s Tamil Tribal Association (TNTA) that had only just formed and was meeting in Sitheri Hills. The Association’s leader, P. Shanmugam went to Vachathi on July 14, 1992. Then CPI(M) State secretary and Rajya Sabha member A. Nallasivan wrote to then Chief Minister Jayalalithaa asking for a judicial inquiry, followed by another letter to the CM by Mr. Shanmugam.

However, the only official statement from the government came through its forest minister K.A. Sengottaiyan, who, on the floor of the House called the violence fabricated and said that the raid was justified because the village residents were sandalwood smugglers. The government refused to take cognizance of an enquiry report conducted by one-person commission B. Bhamathi, an IAS officer and then Director of the National Commission for Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, filed after visiting Vachathi in August 1992.

The TNTA’s petition was dismissed by the Madras High Court under judge Padmini Jesudurai (also the first woman judge) implying that the accused persons were educated, and not capable of such crimes. Subsequently, Mr. Nallasivan moved the Supreme Court in this regard.

Last month’s verdict observed how the police had refused to register a complaint; how the court ordered a CBI investigation only in 1995 three years after the crimes, and the trial itself commenced 10 years later, with, finally, a judgement delivered in a case that never had an FIR filed.

Reparation for State violence

The 2011 verdict ordered compensations that have still had not reached all the survivors. “Cheques of between ₹34 and ₹38 lakh were returned because there were changes in names, initials amd some living heirs did not have heir certificates. The cheques were never handed over to them,” says Dilli Babu.

The Madras High Court verdict uniquely invoked ‘Command Responsibility,’ pulling up the then District Collector, and Superintendent of Police for the crimes on Vachathi’s people and ordered “stringent punishment” for them.

The Court was clear, “In order to safeguard actual smugglers and big-shots, the revenue officials, police and other forest officials with the help of officials and the government played a big stage drama in which innocent tribal women got affected…The then government failed to protect the innocent tribal women and instead worked to protect erring officials and failed to find out the real sandal wood smugglers,” the court observed.

Mr. Dilli Babu also wants to hold a few more persons accountable: “Former Minister Sengottaiyan, who called the violence fabricated and branded the people of Vachathi, must now give us an answer,” he says.

Nothing can really erase the memories of pain, violence and humiliation that two generations of people in the village have suffered, says Rani. “Compensation only helps us pick up our lives afterwards and perhaps helps our children. “Our mothers had passed on with only that memory of pain. They [the State] called us smugglers, they called us names. Now that shame is erased,” she says.

As instances of State impunity deepen, as seen in the many custodial violence cases T.N. has witnessed of late, it took the women of Vachathi 30 years to summon ‘Command Responsibility’ and establish that State actors have no right to absolute immunity, but are subject, as every other citizen is, to the rule of law.

(Names of survivors changed to protect identities)