It is 25 years since political leaders struck the Good Friday Agreement, the landmark peace accord that ended three decades of violence in Northern Ireland, a period known as “the Troubles”.

That dark time in Northern Ireland, involving bombings and shootings that killed 3,600 people, began after the suppression of a civil rights march in Derry in October 1968.

Tensions between nationalist Catholics and unionist Protestants deteriorated into a bloody and brutal battle over whether Northern Ireland should be part of Britain or the Irish Republic.

The clashes involved Irish republican militants, loyalist paramilitaries and UK troops.

As public fury at the repeated violence and deaths mounted, the IRA (Irish Republican Army) called a ceasefire in 1994, allowing Sinn Fein to join other nationalist and unionist parties in peace talks co-sponsored by the British and Irish governments.

The United States played a key role. Former senator George Mitchell oversaw the delicate multi-party negotiations.

The talks came close to collapse several times, but after a negotiating session that stretched long past deadline, agreement was reached on 10 April 1998 — Good Friday.

The then prime minister Tony Blair said: “Today I hope that the burden of history can at long last start to be lifted from our shoulders.”

The following month, the agreement was ratified by voters in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The agreement ended direct UK rule of Northern Ireland and set up a legislature and government with power shared between unionist and nationalist parties.

Four months after the agreement, IRA dissidents planted a car bomb that killed 29 people in the town of Omagh, the deadliest single attack in Northern Ireland.

Despite more sporadic attacks since then by small splinter groups, the peace has held. But those who lived through The Troubles will never forget some of the scenes they saw.

In the Falls Road curfew in July 1970, the British army sealed off the nationalist area for three days in the search for weapons. Four civilians were killed. Days later, a civil-rights protest was staged.

Bloody Sunday, on 30 January 1972, when British soldiers opened fire on 26 unarmed civilians in the Bogside area of Derry, was one of the darkest days of the Troubles.

When paratroopers opened fire on a civil-rights march, 13 people were killed instantly, and one died later. At least 15 other people were wounded.

Seven people were killed when an IRA car bomb exploded outside the headquarters of the 16th Parachute Brigade in Aldershot, Hampshire, on 22 February 1972. Nineteen people were also injured in the attack that was retaliation for Bloody Sunday.

Checkpoints enabled British soldiers to search local shoppers and their bags for weapons or explosives.

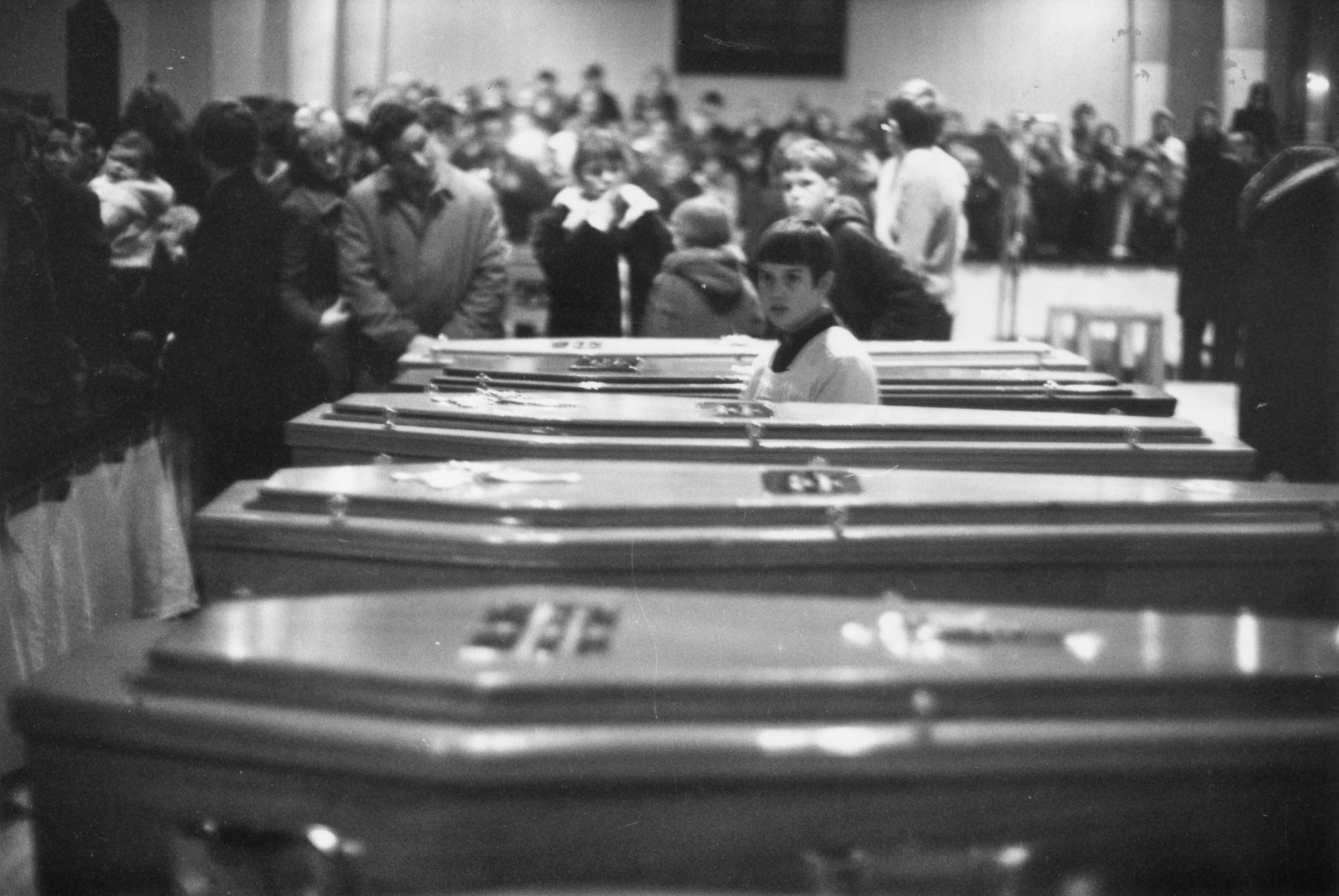

On 17 May 1974 three car bombs in Dublin exploded almost simultaneously, in Parnell Street, Talbot Street, and South Leinster Street, killing 23 men, women and children. Three others who had been wounded died over the next few days.

On 12 October 1984, an bomb planted by the IRA went off, killing five people in the hotel where Conservative politicians were staying for their party conference. Then prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who had been the target, survived, but trade secretary Norman Tebbit and his wife were injured.

In 1981, Bobby Sands, the IRA’s leader in the Maze prison near Belfast, starved himself to death after 66 days of refusing food. At least 100,000 people lined the funeral route. Sands had been protesting against the removal of “special category status” in jail.

On 11 February 1996 two people were killed when IRA terrorists detonated a large bomb in London’s regenerated Docklands area.

In April 1998 Tony Blair and Bertie Ahern hailed the spirit of “Anglo-Irish teamwork” that led to the historic Good Friday Agreement.

Just four months after the agreement was sealed, on 15 August, 1998, a car bomb exploded in Omagh, co Tyrone, killing 29 people and injuring more than 200 others. The Omagh bombing, carried out by members of the Real IRA, was the deadliest attack of the three-decades-long conflict.