On May 28, Border Patrol picked up a 16-year-old Honduran girl who had crossed the Rio Grande with her 8 month-old-infant, and sent the young mother and her child to a border processing center in Texas dubbed the perrera (dog pound). There, she said, officers took her daughter’s clothes, milk, and medicine, and put them both in a three-sided cage packed with other migrants. “My baby was naked outside with no blanket for all four days we were there,” she later told attorneys who were investigating whether the U.S. government is violating law by holding kids in unsanitary and unsafe facilities. “We were freezing, [and] my baby couldn’t sleep because the ground was cement with rocks,” she said. “Every time she moved, the sharp ground would scratch her. There were many pregnant women who had to sleep on rocks, and I felt very badly for them.”

From there, the teen mom said, she and her baby were transferred to Ursula, a CBP processing center in McAllen, where they encountered the kind of conditions that have dominated news reports in recent weeks: packed cages, sick and crying babies, inedible and insufficient water and food. When her baby had a fever and began vomiting and having diarrhea, the teenager said she asked for help and the guard responded, “She doesn’t have the face of a sick baby. She doesn’t need to see a doctor.” The food made them sick, and they both lost weight, she said. The baby couldn’t sleep and cried frequently. They couldn’t shower for the first eight days in the McAllen facility.

“I am very scared and anxious,” the girl said in her declaration. “It makes me feel very bad the way they treat us. It is hard being so young and being a mother.”

Over the last month, media reports have detailed horrible conditions at Border Patrol facilities and the danger to kids being held there. But advocates and lawyers who visited describe the particular vulnerability of teen moms in detention—kids themselves who are trying to care for new babies in conditions that have been compared to “torture facilities.” Testimonies from teen moms in border processing centers, taken as part of a temporary restraining order filed against the U.S. government in late June, describe similar conditions.

“There is no water or soap to wash our hands or the baby. We have only been allowed to shower and brush our teeth one time since we arrived 12 days ago,” said a 16-year-old from Guatemala with a 1-year-old son. “I am very scared and anxious. I worry about my baby because he is sick and I don’t know what will happen to us.”

“Once, I needed clean clothes for my baby because she threw up, but when I asked for them I was told they didn’t have any available. She is still in the same dirty clothes,” said a 17-year-old Honduran mom with a 1-year-old daughter.

“My baby has not eaten a full meal in 15 days. I am very worried and don’t know what to do,” said a 16-year-old from El Salvador, who has a 26-month-old son.

“I have trouble sleeping at night because of the cold. My son get so cold he feels frozen to the touch. The lights are on all the time. There is lots of noise all the time because they are girls and children who can’t sleep and who cry a lot. We are all so sad to be held in a place like this,” said a 17-year-old from Honduras, whose son’s age was not specified.

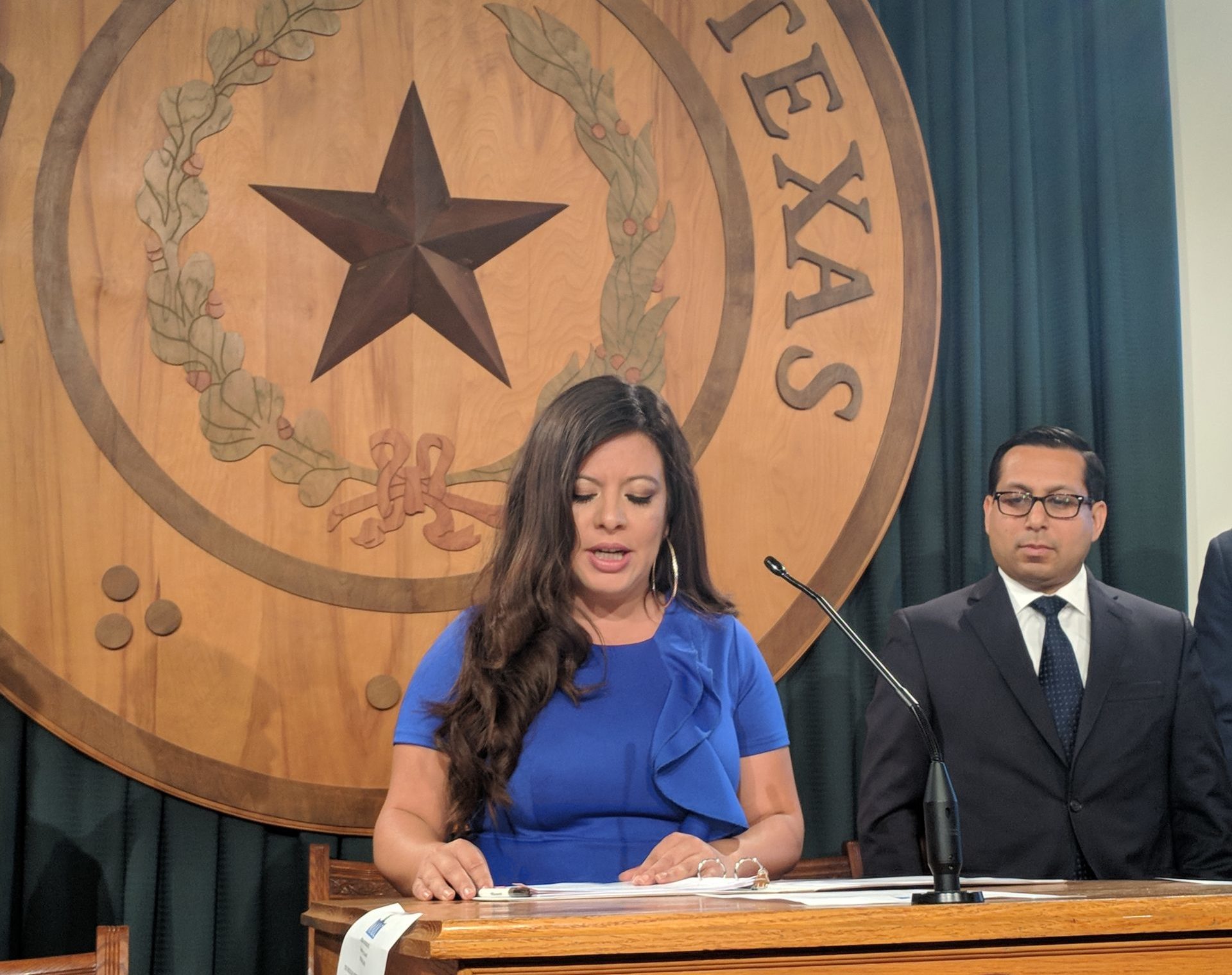

Most of these facilities are meant to hold adults, not families and kids, and certainly not for long periods of time. But the Trump administration has skirted the federal laws that limit the detention time for kids, leaving them locked for days, even weeks, in unsafe conditions. “The reality is a lot of the people who now are coming over are not single adult males; they’re women, they’re children, they’re teen moms,” says state Representative Mary Gonzalez, a Democrat who represents Clint, Texas, home to one of the most-scrutinized facilities in the country. “The Border Patrol hasn’t shifted their operations to accommodate for that reality. So what ends up happening is a lack of resources and a lack of understanding of the needs of teen moms.”

Hope Frye, an immigration attorney, says she met a 17-year-old girl in the Ursula facility in McAllen who had undergone an emergency C-section in Mexico a month before. When they spoke, Frye says, the girl was cradling a listless, premature infant wrapped in a dirty sweatshirt. The teen, who had been at the CBP facility for several days, was bent over in a wheelchair, unable to walk from pain. Frye, who has organized visits for attorneys to CBP facilities for years, brought the story to the media, worried officials would do nothing and fearing the girl and her baby would die in the processing center.

Frye says she only found the girl because she started her visit to Ursula last month by interviewing the youngest unaccompanied migrants, children less than a year old, and realized some of those babies were children to teen moms, themselves considered unaccompanied minors. “It was a horrorshow,” she said of the conditions. “Every baby was sick, it was just a question of the severity,” said Frye, who was herself hospitalized with a severe case of the flu following her visit. “Moms were exhausted, sick. They were terribly worried, overwrought about their kids. There’s a kind of exquisite vulnerability to those children,” she told the Observer. “How are they supposed to be able to advocate for themselves or their children in that kind of a setting?”

Asked about conditions for teen moms and any changes made since last month, a Customs and Border Patrol spokesperson directed the Observer to testimony from acting Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kevin McAleenan in mid-July. McAleenan downplayed reports from the facilities, but added that the situation remained “beyond crisis level.” According to his testimony, the number of kids held and average time spent in CBP facilities fluctuates, but has been reduced since last month, due in part to the construction of more centers to reduce crowding, as well as Trump’s controversial “Remain in Mexico” policy, which sends migrants back to Mexico, often to dangerous border towns where they must await their asylum court hearings.

Attorneys who’ve been visiting border processing centers and detention facilities for years say the conditions have long been inadequate, even unsafe, but that recent conditions have been far worse. Last year, hundreds of migrant kids and parents filed court briefings citing similar mistreatment in Border Patrol facilities ranging from rotten food to verbal and physical abuse as well as a lack of medical care. One account said that guards treated teens in custody “worse than dogs.”

Among the most disturbing images to have stuck with Elora Mukherjee, director of Columbia Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, from her time in Clint last month were the breastmilk-stained shirts of the two teen moms who she interviewed, ages 16 and 17. The girls, who traveled to the United States from El Salvador, hadn’t been able to change since crossing the border days and weeks, respectively, before. “When I became a mom for the first time, I had no idea about how breast milk can just leak out of your boobs when you’re nursing,” Mukherjee, who has three kids, said with a laugh. “These mothers had no chance to change their shirts, and their shirts were covered in breast milk stains. And breast milk that’s not fresh starts to smell really bad. And when breast milk dries up on clothing, the shirt is no longer soft, it stiffens up,” she said. “I can’t imagine how dirty they felt and how uncomfortable they felt.”

Meanwhile, a pediatrician who interviewed kids in the Ursula facility last month told the Observer that teen moms who were breastfeeding were given half as much water as is recommended each day, and reported inadequate milk supply as a result. “They are not getting enough water and food really to feed a baby,” said Dolly Lucio Sevier, a Brownsville doctor. “There was a baby that was losing weight, breastfeeding mothers that were saying they were losing weight.” There was no way to wash the formula bottles and nothing to eat but solid adult food like burritos and cookies, she said, leaving infants at risk for iron deficiency and anemia.

The teen moms in the McAllen facility “weren’t able to take care of their babies in the way they wanted to,” said Mukherjee, who has worked on issues related to the treatment of migrant kids in U.S. custody for more than a decade. “All the critical decision-making power, the caregiving power, is stripped from parents when they’re in facilities like these. Parents cannot decide when their child wakes up, what to feed their child, when they play outside,” Mukherjee told the Observer. “A parent can’t turn off the light in facilities like Ursula, they can’t raise the temperature if it’s cold.”

Doctors warn that even short-term detention can cause long-term trauma for kids. This trauma no doubt extends to parents who are just kids themselves.

READ MORE:

-

‘Treated Worse than Dogs’: Immigrant Kids in Detention Give Firsthand Accounts of Squalid Conditions: Hundreds of immigrant children and parents in federal detention facilities say they’ve endured inedible food, verbal and physical abuse and a lack of medical treatment.

-

Doctor Details ‘Insane,’ ‘Demoralizing’ Conditions for Kids at Texas Migrant Detention Center: A pediatrician talks to the Observer about her recent visit to a South Texas detention facility.

-

How Trump Shredded What Little Protection Our System Offers Migrant Kids: The administration uses emergency exceptions to break government rules for detaining migrant minors. What happens when that becomes the norm?

-

In Matamoros, Asylum-Seekers Wait, and Wait and Wait: Refugees stranded across the border from Brownsville endure interminable delays, leading some to brave the Rio Grande.