Marion Ehrlich turned 5 on January 27, 1933, a few days before Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. If she was too young to fully appreciate the significance of his elevation, she was surely old enough to sense the fear it must have caused in her family—she lived with her parents, Hugo and Gertrud, and an older brother, Gerd, who was 10—and among other German Jews. Did she have any kind of a birthday party that year? Was anyone in the mood to celebrate? Maybe, for a time, ordinary life went on.

The Ehrlichs were not practicing Jews, but they could not have ignored the effects of the Nazis’ rise to power for long. By the spring of 1933, a new law limited the number of Jewish students allowed to attend German public schools (Marion eventually attended a Jewish school); in September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Nuremberg race laws, laying the groundwork for the legal persecution of Jews.

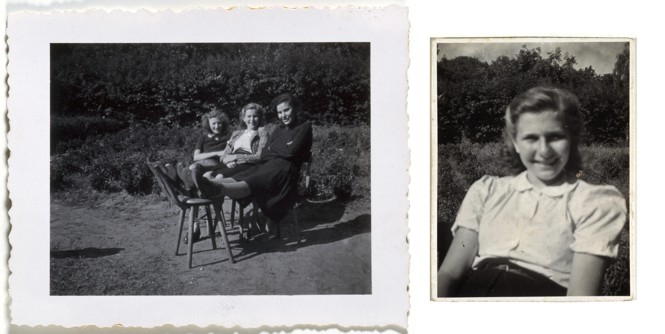

In 1940, Marion Ehrlich was a student at the Jewish middle school in Lindenstrasse, Berlin. (Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Harry Kindermann)

In 1937, when Marion was 9, the city of Berlin celebrated its 700th anniversary; Nazi flags hung from the Brandenburg Gate, and parents brought their children to watch the celebratory parade. That year, the Ehrlichs moved to an apartment at Giesebrechtstraße 15, in the Charlottenburg neighborhood. During the Kristallnacht pogroms, in November 1938, Marion’s father, a lawyer, was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He was released from the camp in 1940, but died later that year as a result of his imprisonment.

The apartment at Giesebrechtstraße 15 grew more crowded as other Jews who had lost their own home moved in with Marion and her family; its seven rooms eventually housed 14 people. The family was first threatened with deportation in 1941.

In 1942, when the last remaining Jewish schools were closed, Marion performed forced labor at a Jewish cemetery. She was soon deported, at the age of 14. She died at Auschwitz.

Eight decades later, a record of Marion Ehrlich’s life appears on the cover of The Atlantic’s December 2022 issue. The cover photograph shows a plaque bearing her name, set into the cobblestones outside Giesebrechtstraße 15, in Berlin. Ehrlich’s is just one of tens of thousands of “stumbling stones,” or Stolpersteine, that serve as memorials to people who were victims of the Nazis across Europe. Clint Smith describes the project in his cover story, which asks what the United States can learn from Germany about atonement:

Each 10-by-10-centimeter concrete block is covered in a brass plate, with engravings that memorialize someone who was a victim of the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. The name, birthdate, and fate of each person are inscribed, and the stones are typically placed in front of their final residence. Most of the Stolpersteine commemorate the lives of Jewish people, but some are dedicated to Sinti and Roma, disabled people, gay people, and other victims of the Holocaust.

In 1996, the German artist Gunter Demnig, whose father fought for Nazi Germany in the war, began illegally placing these stones into the sidewalk of a neighborhood in Berlin. Initially, Demnig’s installations received little attention. But after a few months, when authorities discovered the small memorials, they deemed them an obstacle to construction work and attempted to get them removed. The workers tasked with pulling them out refused.

In 2000, Demnig’s Stolperstein installations began to be officially sanctioned by local governments. Today, more than 90,000 stumbling stones have been set into the streets and sidewalks of 30 European countries. Together, they make up the largest decentralized memorial in the world.

Like the Stolpersteine, so many of Germany’s most powerful memorial efforts, Smith finds, “emerged—and are still emerging—from ordinary people outside the government who pushed the country to be honest about its past.” It is in part thanks to their determination that Marion’s story can still be told today.