On October 13, 2014, Anees Ansari, 24, was once again logged into Facebook from his office computer in Andheri East, Mumbai. In the past year, he had already received at least three verbal warnings and two written warnings from his managers for “excessive use of internet during working hours”.

Yet he logged in anyway and struck up a conversation on Facebook Messenger with his friend Omar Elhajj, who lived thousands of kilometres away in the United States of America.

The chat began innocuously enough but soon descended into discussions about attacks on their potential “enemy”, the United States. It ended last October in Anees being sentenced to life in prison.

Anees is the first person in Maharashtra to be convicted on charges of cyberterrorism, leaving behind a bewildered family trying to come to terms with what their son had done – or, rather, what their son had threatened to do. Anees’s lawyer had contended that the police had not presented any evidence that he intended to carry out his “plans”.

But his intent, the police said, was clear.

Anees’s father, Shakeel Ahmad Ansari is baffled. “It is common to hate someone,” he said, speaking to this reporter in Mumbai. “But that doesn’t mean every person who hates someone will kill him, or will be capable of killing him.”

Since Anees’s arrest on October 18, 2014, he has remained in jail. All of his applications for bail, and to be discharged from the case, were rejected.

Anees’s arrest capped a year in which four young men from the neighbouring town of Kalyan travelled to Iraq to join ISIS.

Two years later, the ATS, then under new leadership, initiated a programme to deradicalise young men and women swayed by ISIS propaganda. For those youngsters willing to participate in the programme, the ATS roped in counsellors and members of the clergy who pointed out that terrorist groups misinterpreted religious texts to further their own cause. The ATS managed to deradicalise over 100 young men and women over the course of four years.

Anees would not benefit from the programme.

In 2014, Anees worked as an associate geographic technician – a software professional – at Here Solutions India Private Ltd, an American-Dutch company that develops maps and location technology.

On October 13, 2014, his chat with Omar began with them joking about how his Facebook account had been “blocked” at least a dozen times and how he always managed to find his way back. In his current avatar, Anees went by the name “Usayrim Logan”, the name of one of the followers of Prophet Muhammad.

(Note: For the purposes of this story, the text-speak used in the Facebook conversations has been written in proper English. The images of the conversations contain the actual spellings used.)

After about 30 minutes of banter, the conversation meandered towards the “evil United Snakes of America” – Anees’s words – and why he wanted to take action that would “shake d ground beneath the feet of Obama”.

Anees even presented his target: the American School of Bombay in Bandra Kurla Complex, a school for the children of diplomats and expats.

“American school...that has children from about 10 different allies of America including France and Italy,” he wrote at 9.48 pm. “...nothing hurts the enemy more than this.”

Omar asked him to “reconsider”, to “rethink”, but Anees steamrolled his protests, replying that Omar was best placed to carry out a “lone wolf” attack in the USA. It was, he said, “almost every mujahid’s dream...to conduct them in America…with less than $100…just needs the courage to do it.”

He added, “Do you know of vehicle bombs, IEDs or pressure cooker bombs…thermite bombs, etc?”

Omar replied, “Yeah of course, which warm blooded mujahid does not know of these things…”

Anees and Omar went back and forth over the next hour and a half, Omar asking for a “slice of the action” but needing Anees’s hand-holding.

In the end, Omar agreed that the plans and suggestions that Anees had outlined for him were “awesome.”

Anees said it would be “awesome” if they were “able to implement it” – Omar had “no idea” about the “impact to the whole planet by a small deed”.

He added: “May Allah guide you…A small deed that can help the Islamic state more than any mujahid actually fighting in its front lines…If America realises that its war across the Middle East has actually reached its home ground, then that would be a decisive victory in itself for the mujahideen of the Islamic state and the mujahideen all around the world.”

Twenty-four hours later, Anees posted an image on Facebook that contained instructions to construct a flame-thrower. He tagged 39 friends and captioned it, “Someone should try this…an awesome weapon to terrorize d kuffar…FLAME THROWER!!”

A Facebook friend called Epic Joshua posted a comment:

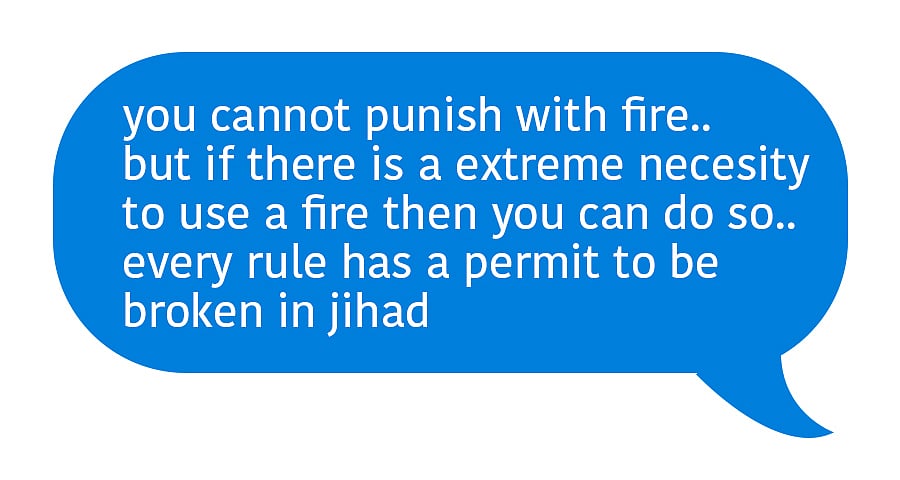

Anees did not entirely agree, replying:

But this exchange did not go unnoticed.

On October 18, five days after Omar and Anees’s chat, the Maharashtra Anti Terrorism Squad (ATS) made its move. A team of officers drove to Kurla East to verify Anees’s address in Qureshi Nagar. Another arrived at the office of Here Solutions in Andheri East.

Anees was at the office at the time. With his colleagues and managers watching, the ATS seized the computers he’d used for the last 12 months and marched him away to its police station in Nagpada. The ATS left behind a letter saying an FIR had been registered against Anees under the Information Technology Act for allegedly exceeding his authorised access of the company’s computers and using them without permission (section 43) and for sending offensive or menacing messages using a computer system (section 66A[a]).

The ATS telephoned Anees’s father at about 10 pm on October 18, 2014.

Ansari mistook it as a call from the local police station, where Anees was scheduled to go the next morning to process his passport application. “I asked the caller, ‘Sahab, appointment toh kal subah ki hai na?’” he recalled. Isn’t the appointment tomorrow morning?

“That’s when the officer said he was calling from ATS Nagpada. He asked me to come down the next morning.”

The ATS investigated the case for three months.

In January 2015, it submitted its chargesheet against Anees and Omar at the Bombay City Civil and Sessions Court. Anees was accused of creating a “fake identity on Facebook” prior to October 18, 2014 and using his workplace computers “dishonestly and fraudulently without taking appropriate permission from the bonafide owner/immediate superior officer who was in-charge of the office premises”.

Between October 13 and 14, he was alleged to have used the computers and internet at his workplace to send “offensive messages” and “support the terror activities carried out by ISIS”. This charge was subsequently dropped after the Supreme Court read down section 66A of the IT Act in March 2015.

The ATS told the court that Anees and Omar had entered into a conspiracy on October 13 to “attempt lone wolf bomb attack at American schools, where small children of foreign nationals are studying”. In pursuance of this conspiracy, Anees had on October 14 “procured information about making of thermit bomb, downloaded the data, released the same, and also passed it on to this other Facebook friends”.

Thus, he had “abetted and agreed with his counterparts to do an illegal act of attempting lone wolf bomb attack at American schools, where small children of foreign nationals are studying, with mala fide intentions to complete his nefarious activities knowing the consequences of the same”.

These actions, the ATS said, were punishable under sections 115, 120B and 302 of the Indian Penal Code, with charges related to abetting the commission of a crime, criminal conspiracy, and committing murder, respectively. Sections 120B and 302 carry punishments of death or life imprisonment.

In the chargesheet, the ATS added a fresh charge – cyberterrorism. With his alleged acts of exceeding his authorised access to his workplace computers and internet, conspiring to attempt a “lone wolf” attack, and sending messages “strongly supporting the terror activities of ISIS”, Anees had intended to “threaten the unity, integrity, security or sovereignty of India”.

Cyberterrorism is punishable with imprisonment, which may extend to life imprisonment, under section 66F of the IT Act. It punishes a person who “causes or is likely to cause death or injuries to persons or damage to or destruction of property”.

The trial began on January 6, 2018. The court eventually dropped the charges filed under sections 302 of the IPC and 66A(a) of the IT Act.

Colleagues, managers, friends and acquaintances, who were summoned as prosecution witnesses, painted a picture of Anees as an extremist, a sympathiser of the Islamic State, and a young man who nursed a deep-seated hatred towards the United States – a man who had conspired to murder children.

The court set October 21, 2022 as judgement day.

Ansari did not attend. He had relocated his family 50 km away to the textile town of Bhiwandi. In any case, he felt the police personnel guarding the court would turn him away, citing Covid restrictions.

Also, he was certain the court would convict Anees.

“We were expecting the court to sentence Anees to seven or eight years’ imprisonment,” he said. “Anees was expecting the same the last time I met him before the judgement. We hoped that after serving his punishment, Anees would have an opportunity to rebuild his life.”

But Anees was sentenced to life imprisonment. In his verdict, additional sessions judge AA Joglekar observed, “The proved offence against the accused is certainly a detriment for society and may have caused or likely to have caused injury to the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India and the security of the state and public order.”

Ansari does not excuse his son’s posts and messages but the heart of the matter, for him, is this: “The ATS did not present any evidence that Anees had made any preparations to carry out what he had written. Agar koi aadmi kisi ko chaaku se maarna chahta hai toh woh pehle chaaku lekar aayega. Par Anees ne toh koi taiyari nahi ki. Woh kisi terrorist ya kisi group ke contact mein bhi nahi tha.”

Loosely translated, if someone wants to stab another person with a knife, he will first procure a knife. But Anees had not made any sort of preparation. He was not in contact with any terrorist group.

But Arun Chavan, then the senior inspector at the ATS’s Nagpada police station who has since retired, said the question of Anees’s capability to carry out the attack is immaterial.

“We could not have waited for someone to die,” he said.

Why, Chavan asked, had Anees acquired the knowledge of assembling a thermite bomb? “He had also found out how to procure the materials to construct the bomb,” he added, saying all that remained was for Anees to assemble the bomb and carry out the attack.

Chavan offered no evidence to back up his claim that Anees had “found out how to procure the materials”. Nor was such evidence included in the chargesheet or produced in court during the trial.

Anees is presently lodged in Nagpur Central Jail.

How did it come to this?

Ansari cannot speak for what Anees was up to when away from home. “He never told me or his mother who he used to speak to on Facebook,” he said.

But at home, Anees never expressed any of the violence he’d shared on social media. “Not with my wife and I, nor with his brothers – and he spoke more freely with his brothers,” said Ansari. “There was no atmosphere at home which could have caused Anees to become radicalised. He never once discussed ISIS at home. Had he become radicalised, we would have been the first ones to notice.”

So, when the ATS called Anees a “jihadi”, it hurt.

Anees and his three brothers received the same upbringing that Ansari had received from his own father. They always played within sight of their front door, never left Qureshi Nagar unaccompanied, and focused on excelling in school. Bedtime was 10.30 pm, even if that meant leaving a family function early. The family prayed five times a day and waking up at 5 am to offer fajr, dawn prayers, was non-negotiable.

Ansari believed in being tough on his children while they were teenagers – it was the only way, he said, that they would become sensible and responsible adults. Every summer, he disconnected the television in the days leading to the end-of-term exams. A computer only arrived in the house in the summer of 2014 and then, too, without an internet connection. Ansari wanted no distractions.

Anees got good marks in school and collected over two dozen certificates for participating in extracurricular activities. He enrolled for a Bachelor of Science degree in information technology and paid part of the fees himself by tutoring students in the neighbourhood studying the same course.

He was also curious about Islamic history, in particular, the conquests and military campaigns of Muslim rules in the Indian subcontinent and Asia. “He would wonder why sections of society badmouthed Muslims and claimed the population of the Muslim community in India is increasing,” said his father.

Anees turned to history for answers. “He used to say, ‘Papa, if it was true that all those Muslim rulers who invaded India from other parts of Asia had converted so many people to Islam, shouldn’t Muslims have been the majority community in India now? But Muslims are still a minority community now, just as they were then,’” Ansari said.

In August 2011, a month after his 21st birthday, Anees joined Here Solutions, forgoing offers from technology firms in Bengaluru to stay home with his family. “He said to me, ‘How will I contribute money to the family’s income if I stay in another city?’” Ansari recalled.

Every payday, Anees handed over almost all of his salary to his parents, keeping just enough to pay for bus fare, his mobile phone bill, and other expenses. “He was so obedient,” Ansari said.

But at his workplace, his reputation wasn’t as pristine.

At Here Solutions, Anees was one among dozens of coders who produced digital navigational maps for clients in a variety of industrial sectors. For the first time, he had a computer connected to the internet all to himself. He wasn’t supposed to use it for anything apart from work. Managers patrolled the office floor like exam hall invigilators, routinely inspecting the computer screens of employees.

Anees was first caught on July 15, 2013 when a manager spotted him reading the Wikipedia page of Musa ibn Nusayr, a general who conquered Africa, present-day Spain and France before his death in 716 AD. The manager read the page and didn’t find anything objectionable or offensive, but he still issued Anees a verbal warning and ordered him to email a screenshot of the page to his reporting manager.

Anees complied, telling his reporting manager that he had been caught on Wikipedia looking up the history of Islam in Spain. “I understand the seriousness of this issue,” he wrote in his email. “This will not be repeated in future and if found then I shall be liable for its consequences.”

Anees was issued a warning letter, signed by his reporting manager, the same day for the “excessive usage of internet during working hour”.

“...we are hereby forced to send this warning letter because we still find no change in your behaviour in spite of all reminders & notices...Please consider this letter as a warning to you that if you have been caught again doing the same activity, it will defiantly lead the management to take a strict action against you,” warned the reporting manager. (Note: All typos from the original.)

On June 11, 2014, the same manager who had caught Anees reading Wikipedia found him lingering over the Facebook page of one Abu Baraa, with whom Anees had seven mutual friends and to whom he had sent a friend request. Once again, Anees emailed a screenshot of the page to his reporting manager: “Hi sir, I was surfing in working hours. My apologies for the same. Won’t be repeated. Thanks, Anees.”

The reporting manager was not impressed. He set up a meeting with the Human Resources department, asking them to take “strict action” against Anees.

A month later, the reporting manager served Anees a second warning: “We would like to state that your repeated internet browsing and surfing of unwanted website tantamount to gross indiscipline and reflects your careless attitude towards your work. This negligent approach towards work is completely unacceptable to us and we would like to state that the management will not tolerate any further indiscipline in this regard.”

Anees was to consider this warning his “one more last opportunity”. Another strike and the company would “be forced to take strict disciplinary action against you.”

During the trial, Anees’s lawyer, Sharif Shaikh, told the court that the employment agreements that new recruits signed with Here Solutions did not contain any clause that forbade them from browsing websites that did not pertain to their work. Nor had the company issued a circular to that effect, said senior managers who deposed as prosecution witnesses. The witnesses also said the company had not penalised or suspended any employee caught flouting that rule.

Shaikh argued that Anees’s use of his computer to read Wikipedia pages and browse Facebook did not mean he had exceeded his authorised use of the company’s computer system. This was a case of misusing access, he said, not of accessing a part of the computer system that Anees wasn’t entitled or authorised to enter.

But in his order, ASJ Joglekar observed that Anees’s employers had granted him access to the internet only to perform his official duties. The webpages he had accessed had “no concern with his job profile”, he said.

It wasn’t just superiors. A colleague working on the same project as Anees often found him texting on Facebook during working hours. She told the ATS that Anees rarely responded when she raised queries related to their project.

“When I tried to speak to him, he would enable the lock screen feature on his desktop. A large black image would then appear on the screen with the words There is only one God, Allah,” she said. “On other occasions, the lock screen image would read Extremist Muslim Graphics Images.”

Anees also fell out with perhaps his closest friend at Here Solutions. They had met in the interview room three years before as fresh graduates and were both hired to work in the production department.

While in office during Ramzan in 2014, Anees texted messages and images of ISIS’s conquest of Syria to this friend on WhatsApp. “I did not like what he had sent and told him so,” the friend told the ATS. “He then sent me a text on WhatsApp that my head was full of shit.”

Minutes later, the friend said, he bumped into Anees in the restroom. Already seething at the rebuke, he confronted Anees. “He said I wouldn’t understand and walked away,” the colleague told the ATS. He blocked Anees on WhatsApp the same day.

It was the last time they spoke. The colleague was among those who deposed during the trial as a prosecution witness.

Not long after Anees’s arrest, the Ansaris moved out of Kurla. The neighbourhood no longer seemed welcoming.

By then, Ansari had moved to his third profession. He had started off as a draftsman in Qatar in the 1980s. He returned to Mumbai at the end of the decade and spent the next 20 years writing articles for the entertainment pages of Hindi and Urdu dailies.

The advent of computers in newsrooms pushed him out. Journalism may not have paid much but it was enough for Ansari to make rent and educate his children.

“I couldn’t make the shift to a new technology,” he said. “I found learning how to use a computer too daunting.”

In Kurla, Ansari found work as a security guard with a private security company. It went smoothly until the day the ATS rounded up Anees. Between having to report to the police every few days, attending court, and meeting Anees in jail, Ansari missed too many days of work.

His neighbourhood was also not as hospitable as it had once been. “Many relatives distanced themselves from us,” he said. “Not because they believed that Anees was capable of committing the crime the police had arrested him for, but because they feared being harassed by the police if they stayed in touch with us.”

But opinion in Kurla had begun to change much before Anees’s arrest. Just like the work colleague, Anees had sent violent ISIS videos to three men his age in the neighbourhood. All of them marked him out as sympathetic to the Islamic State.

Anees met the first two men – a pharmacist and a medical representative – at the local mosque. Whenever he had the afternoon shift at work, Anees would pray at the mosque before taking the bus to the office. His views soon reached the ears of the mosque’s trustee, who advised other regular attendees to steer clear of Anees.

The third man was a tuition teacher who ran a coaching class, where Anees had briefly taught English grammar in 2013. They were friends on Facebook until one day in June 2014 when Anees unfriended and blocked him. Some days later, when the teacher asked him why, Anees said, “That’s because you have the intellect of a child.”

Given all this, it was easier and cheaper for the Ansaris to make a clean start in Bhiwandi. Once there, Ansari found the daily commute to work impossible. So, he quit.

Three questions that the defence raised during the trial went unanswered, according to advocate Shaikh.

The ATS accused Anees of “procuring information about making a thermite bomb” and sharing it with Omar. Advocate Shaikh argued that the only context in which a thermite bomb was mentioned in the Facebook chat was when Anees asked Omar if he knew what it was. Anees had posted an image of a flame thrower on his Facebook timeline. “It is not a thermite bomb,” Shaikh argued.

Second, Shaikh argued that Anees had not instigated Omar to commit a “lone wolf” attack in the US. “From the argument,” Shaikh said, “there seems to be no agreement” between the two men. On the other hand, Shaikh said, Omar had tried to dissuade Anees from attacking a school and had asked him to reconsider his plan. Anees had not responded when Omar asked him if he planned to go through with the plan, Shaikh argued.

ASJ Joglekar found this conversation sufficient proof that Anees had abetted Omar to commit a “lone wolf” attack.

Third, the defence flagged as suspicious the manner in which the ATS had written to Facebook seeking details of Anees’s account. In a letter sent to the social media company on the day of Anees’s arrest, the agency said Anees’s email address had come to be “adversely reflected” in its investigation into a low-intensity improvised explosive device blast outside Faraskhana police station in the heart of Pune city on July 10, 2014. Six people were injured in that blast.

Shaikh questioned how the ATS had sought information from Facebook on October 18 when it only completed its examination of Anees’s email addresses and Facebook account, and printed out dozens of pages of conversations, in the early hours of the next day.

Shaikh also argued that Anees was not a suspect in the Pune blast case. Senior inspector Chavan told this writer that he was certain Anees had no role in that blast. The ATS had suspected the involvement of the banned Students’ Islamic Movement of India, or SIMI, in the blast. Although no arrests were made in the case, all five suspects are now dead. Two were shot dead in an encounter by the police in Telangana in April 2015 and three others were killed by the police in Madhya Pradesh in November 2016 after escaping from prison.

This fact did not find any mention in the judgement.

Finally, the ATS was also unable to locate Anees’s fellow conspirator, the American national Omar. While Chavan was overseeing the investigation, the ATS had begun the process of seeking his details from the US government. However, the ATS could not trace his whereabouts and bring him to India to face trial. Omar’s absence was not commented upon in the judgement.

On the balance of the ATS’s evidence, ASJ Joglekar was left in no doubt that Anees intended to attack the school. He did not find any merit in Shaikh’s arguments that, despite exceeding his authorised access to the computer system at his workplace, Anees had ultimately caused no damage to the organisation.

The judge observed, however, that the question under consideration was not of the damage to Anees’ employers but “it is the state qua the national security at the other end which was to accrue such irreparable damage and that cannot be compensated in terms of money.”

The verdict has not answered the question eating away at Ansari for over eight years – where was the evidence that Anees had turned his words into actual preparation for attacking the school? ”Iss ladke ne ghar pe choohe ko tak nahi maara hai.” This boy had not even hurt a mouse at home, he said.

Newslaundry is a reader-supported, ad-free, independent news outlet based out of New Delhi. Support their journalism, here.

.jpg?w=600)