“I think people should dance,” jazz legend Ray Brown once said. “There are enough musicians in the world that a certain percentage of them shouldn’t worry about being great soloists. They should play in jazz bands and get people dancing again. If the people like it enough to dance, then they’ll enjoy playing.”

Ray had seen a lot in his time, playing for the likes of Benny Goodman, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, and his words still ring true. Sometimes the bass world idolizes soloists – often musicians playing for other musicians – when the rest of the world just wants to dance.

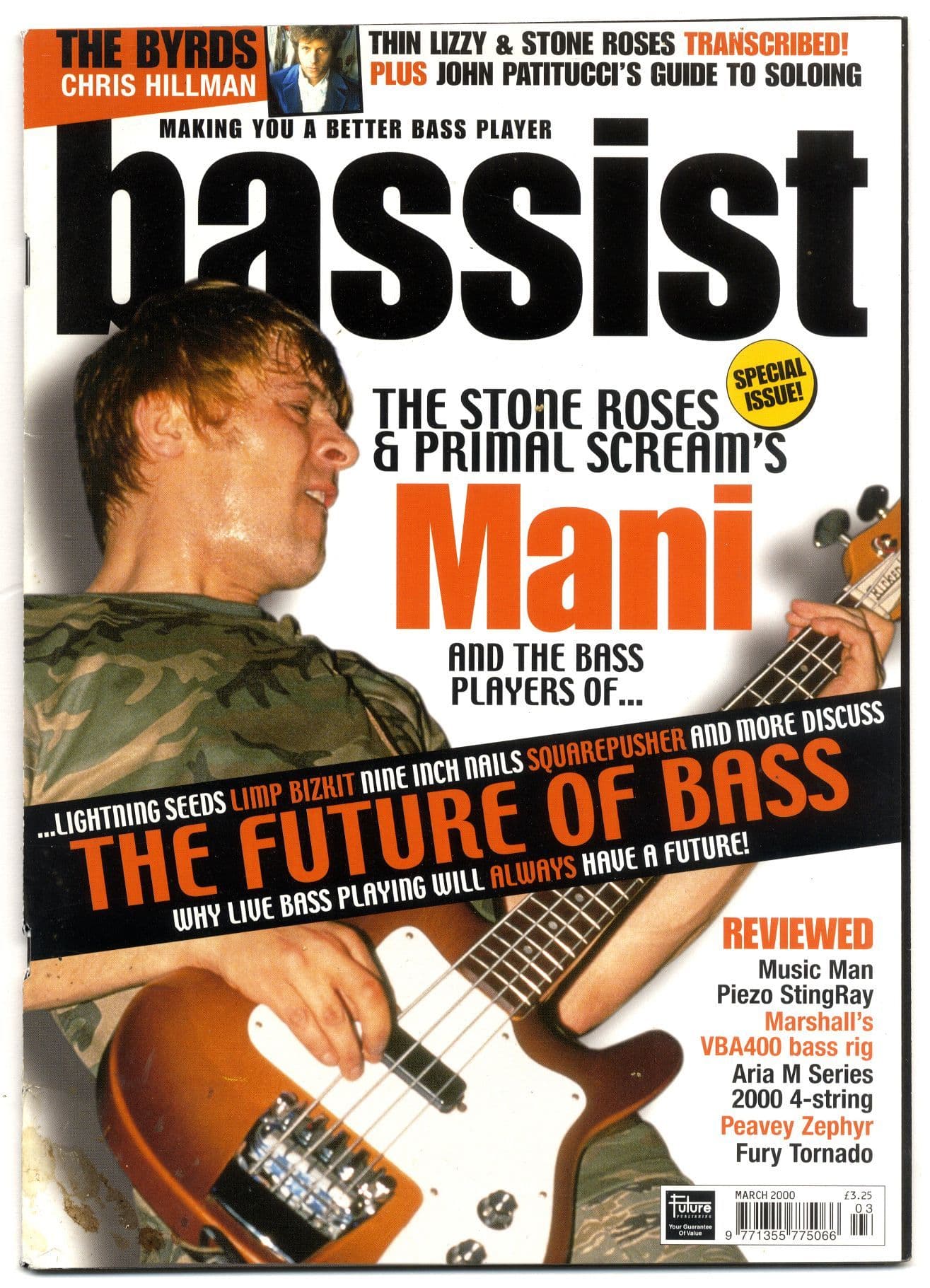

Enter Gary “Mani” Mounfield. When Mani came into prominence in the late 80s and early 90s, bass was everywhere. Acid house, techno, drum’n’bass, hip-hop: the new music was bass-heavy but very little of it featured an actual bass player. Alongside fellow Mancunians the Happy Mondays, the Stone Roses introduced a whole generation of rock fans to the joy of dance music and club culture. The music of the Stone Roses was a molten mix of 60s psychedelic pop (chiming guitars, lush melodies) and a groove that fitted right in with the acid house explosion, capturing the hearts of indie-kids and clubbers alike, powered by one of the best rhythm sections of the decade.

Ask Mani if he and Roses’ drummer Reni deliberately set out to get people dancing and he'll look at you with disbelief: "That's what the bass and drums are for, aren't they?" he says, laughing and frowning at the same time. "That's what they're for."

This interview with Mani is from March 2000, around the release of XTRMNTR, his second album with Primal Scream – the band he joined in 1996 and stayed with until 2011 – and we looked back over his career so far. The young Mani was a rhythm guitar player who picked up bass for a band called The Waterfront featuring one John Squire on guitar and occasionally a guy called Ian Brown on vocals. He was pleased that he'd switched. "I found it more rewarding playing the bass guitar than playing rhythm," he remembers. "I've always been into good old Northern Soul and funk grooves and it was like, 'This is it’.”

Learning by ear (“Put a sheet full of dots in front of me and I wouldn't have a bloody clue what's going on," he says), Mani says he was still a bit of a beginner when he joined the Stones Roses proper with Ian Brown on vocals, Squire on guitar and an amazing drummer called Alan Wren ("Reni").

"That was just the most exciting time," he says. "To be locked in tight with a guy who, for me, must be the best drummer I've ever seen in my lifetime. I was still a bit of a novice when I came to join the Roses, so I learned a hell of a lot from Reni, John and Ian. It brought me along leaps and bounds. Playing with a great drummer like that is beneficial for your style. You can learn lots of tricks. He taught me a lot, Alan Wren, and I'll be eternally grateful to him for that."

The band were part of new indie-pop scene: definiantly anti-macho psychedelic rock in thrall to the sounds of Love and The Byrds. Initially, they were inspired by a little-known indie pop band from Scotland called Primal Scream. "There's a lot of parallels between the Stone Roses and the Scream," says Mani. "We all wanted to be Roger McGuinn or Chris Hillman of The Byrds. We had a similar style."

Alternative music in the 80s had often been angular, difficult and dark: the Stone Roses were melodic, bright and groovy. "It couldn't really be helped," explains Mani. "Ian and John are both big Sly Stone and Northern Soul fans, so I suppose you can't help but wear your influences on your sleeve. We were always – I wouldn't call it pinching – recycling our favorite grooves.” He laughs: "We were very eco-friendly about it, y'know?"

On the songs that became their calling cards – epic tracks like I Am The Resurrection, Fools Gold and One Love – the rhythm section held the track together, allowing guitar-hero Squire to layer it with abstract, funky riffs. "It's good when you've got a rhythm section as tight as that," says Mani. "It totally frees up your guitarist or vocalist to do exactly what they want over the top. It was good for John – he didn't have to worry about rhythm guitar 'cos the rhythm was set in stone anyway. It helped him a lot.

"I'm always nit-picking, but One Love could've swung a little more. It's a little bit rigid. But it was a good enough idea at the time. With Fools Gold, it was going to be the b-side to What The World Is Waiting For. I just started fucking about on keyboards, trying to put a keyboard bass down, and we got a funky drum loop off of Reni and sampled that – the first time I'd ever really explored the world of sampling – and just came up with the bass line. And then John spoiled it all with lots of wah-wah guitar and shit, the bastard," he says laughing. "Only joking."

“I've been playing a weird little 3/4 scale Rickenbacker. I think it's a 3000 or an Eldorado or something. It's as rare as rocking horse shit. I got one with the Roses, right, and I've had that about five years but it's getting a bit tatty now - there's nothing left on the truss rod - and l've just managed to find another one. And remember my big paint-splashed 4005 Rickenbacker semi-acoustic? l've got a really sexy black one of them as well..."

What is it you love about Rickenbacker?

"I don't know - I just really like the tone and the attack and everything you get on them. It's a fucking man's bass! [laughs]. And l've got a little Gibson EB-0 with that Angus Young guitar shape. I've got a couple of them, a couple of Precisions, a nice Jazz which I hardly ever play any more... I fucking love guitars, man. You can never have enough! And l've got this really weird Dan Electro thing as well, real 60s shape, and if you put on flatwounds or those black placcy strings, and get tons of reverb on it, you're just Scott Walker-ed right up, man! Amazing."

After the massive success of Fools Gold and the first album, the band went into seclusion for five years, battling their record company Silvertone in the courts and recording follow-up album The Second Coming in-between. Long-time producer John Leckie quit during the recording ("I think he felt that they didn't have enough songs," said the guy who replaced him, Simon Dawson), and they built the album out of long jams. As NME reviewer John Harris, giving it 6/10, acknowledged: “anything other than a stone cold classic that sounded like it had been beamed in from another plane was going to be a jarring anti-climax.”

More indebted to Led Zeppelin than Love, it was an inevitable disappointment – despite some great songs (Ten Storey Love Song would’ve fitted on their first album, Your Star Will Shine displayed a Beatles influence – an upcoming band called Oasis would grab that baton and run with it) and brilliant performances and bass parts.

"I'm really into The Second Coming at the moment," says Mani. "So many people just pissed that off without really studying it. I think they wanted something that we'd done before but we were never about to do another Herman Hermits album like the first one and be loveable mop-tops. We'd grown hair on our balls and learned to play a bit better and we were always going to do something a little bit different.

"It's very guitar-y. I'm sure that if John Squire could have his time again he strip a lot of the guitar out of it and revert back to the groove. But I think it really stands up now.”

While the Stone Roses crumbled under the weight of expectation, and Oasis stole the audience they’d cultivated, Primal Scream became the band at the forefront of the dance-rock crossover. From the release of their classic third album Screamadelica in 1991, Primal Scream were just as likely to record with Stones producer Jimmy Miller as maverick dance producer Andy Weatherall, collaborating with George Clinton, Jah Wobble and reggae legend Augustus Pablo along the way. Mani and the Primals were made for each other.

With Mani on board, Primal Scream did what they'd always threatened to do – made genuinely groundbreaking music. Vanishing Point, their first album with Mani was a bass-heavy slice of dub, funk, grinding rock and blissed-out pop like no other. XTRMNTR pushed the boundaries even further: a thrilling, aggressive, angry and uncompromising beat and bass-driven album.

What strings do you use?

"I've always been a roundwound Rotosound guy, just medium gauge, medium scale and all that, but [Andrew] Innes [Primal Scream guitarist] has been turning me on to the flatwounds now - just a different tonal quality, good for a song where you don't have to be attacking as much.”

Plectrums or fingers?

"Fingers. It's something I've grown into. In the early Roses days I was more of a plec-head 'cos technically I wasn't good, my style wasn't as good as it could've been. I just graduated on to playing with fingers – you can get more of a feel. On the first Roses album I might've used fingers on Waterfall but it was mostly just plectrum. But now – as I've got smarter and cleverer over the years – I just let my fingers take control now, man. [laughs]"

Amps?

"Well, I started out with Ampeg SVTs and moved on to Mesa Boogie 400 Plus. Fucking trouser flappers, man. They get the trouser properly flapping. Really good. And I've got some Ashdowns to try and I quite like the sound of that, but I'm still basically Rickenbacker and Mesa Boogie.”

Do you use many effects?

"Just a Colourtone Fuzz pedal on a couple of tunes, but it's something I might explore. I've always just been a fucking bog-standard kind of guy. My roadie has the easiest job on the tour. I use a bit of funky tuning on a couple of tunes, but that's about it. I tune the E down to D on a couple of tunes to get that heavier octave thing on songs in D. I tune [Primal Scream song] Star into F# - it's just to save me from working it out somewhere else! I'm a lazy bastard - I just get my guy to tune the E to F# and then play it in my normal position."

Ironically, whilst musicians criticized the dance revolution for being synthesized and artificial, the profile and importance of bass in that music (whether programmed or real) rose steadily. Hip-hop throbbed from car stereos, techno producers spent hours getting the right bass sound, classic dub and soul bass lines appeared in ambient and trip-hop, and drum'n'bass stripped the music right down, reinvigorating the double bass along the way. And while bass became more celebrated and prominent in dance music, it all but disappeared in rock.

"Dance music is very bass driven," says Mani, simply. "With rock'n'roll you always get some shit-hot guitar player stealing everyone's thunder, y'know?" he laughs. "Bass is mega important – anyone who's got an ounce of groove in them realises that."

Primal Scream occasionally use programmed bass as well – could a computer ever replace live bass playing? "Oh, I hope not," he says laughing, "or that's me back on the dole, innit? There's room for co-existence between the two I s'pose, but nothing can beat the thrill of seeing someone poking about with a fucking guitar around their neck. Much as I like dance music, I'll always be a sucker for the organic bit of wood with four strings on it."

What can a live bass do that a sampler can't? "I dunno but I think you look sexier with a bass around your neck than a fucking sampler, y'know what I mean? You can't beat the feel of a human playing. Humans play the machines and, like I say, it works well but people want to see…" he searches for the answer: ”…me, pogoing around with a bass, gurning and going fucking mad and dropping licks."

There's no replacing a live drummer either, as Mani knows: not long after he first joined Primal Scream, drummer Paul Mulreaney left and they toured with a drum machine. "That was pretty difficult," he says, "cos, y'know, it don't mean a thing if it ain't got that swing. It's much better now I've got Darrin Mooney [Primals drummer from ‘97-now] to bounce off – he's an awesome drummer as well, so it just makes the bass mean so much more. With a drum machine, it's OK, but you're very constricted in what you can do. You can't look over your shoulder and go like, 'Whip it up' and shit like that. You're just stuck within those parameters."

With the Stone Roses his style was fluid, funky and melodic, with the Primals his bass is more distorted, dubby and driven. "I was always into that style of playing," he says. "I suppose I was just playing against myself in the Roses. There was more onus on me to show off a bit more, 'cos John was licking away and Reni was licking away so there was a bit of ‘I’Il fucking show how good I am' sorta thing. It's good with the Scream to strip your sound down and make the space work as well as the notes. I wasn't conscious of changing, but now you've made me think of it…

"I always wanted to be at the forefront as well, but it's just that in my old band I had to battle hard against three other fucking excellent guys. It was tough going. But the Scream is good and we all have our own room to move… They're not too precious about technology either: on certain tracks they'll use a programmed bass or a drum machine - whatever works for the song...

"If a programmed bass works better than a played bass, then programmed bass it is," says Mani. "There's no sense in getting a bad head on about it. It's all for the good of the tracks."

He's got a liberal attitude towards sampling too, having had his bass lines used elsewhere a couple of times, first of all on Tunes Splits the Atom by Manchester rapper MC Tunes – a UK top 20 hit in 1990 – which nicked a bit of his classic I Am The Resurrection riff. "I know Tunes really well and it was just like: 'Use it man, I don't want no money off you, just make music with it’. And I'm pleased he did. Being sampled is probably the ultimate accolade.

"When Fools Gold was sampled by Run DMC I thought, ‘Here's Mister fucking Whitey being sampled by some black hip-hop monsters,’ man. I was like, come on. That for me was the ultimate buzz. I've always been into that kind of music and here was me, some white guy from Manchester, getting sampled by one of the biggest hip-hop bands in the world, man. It was amazing."

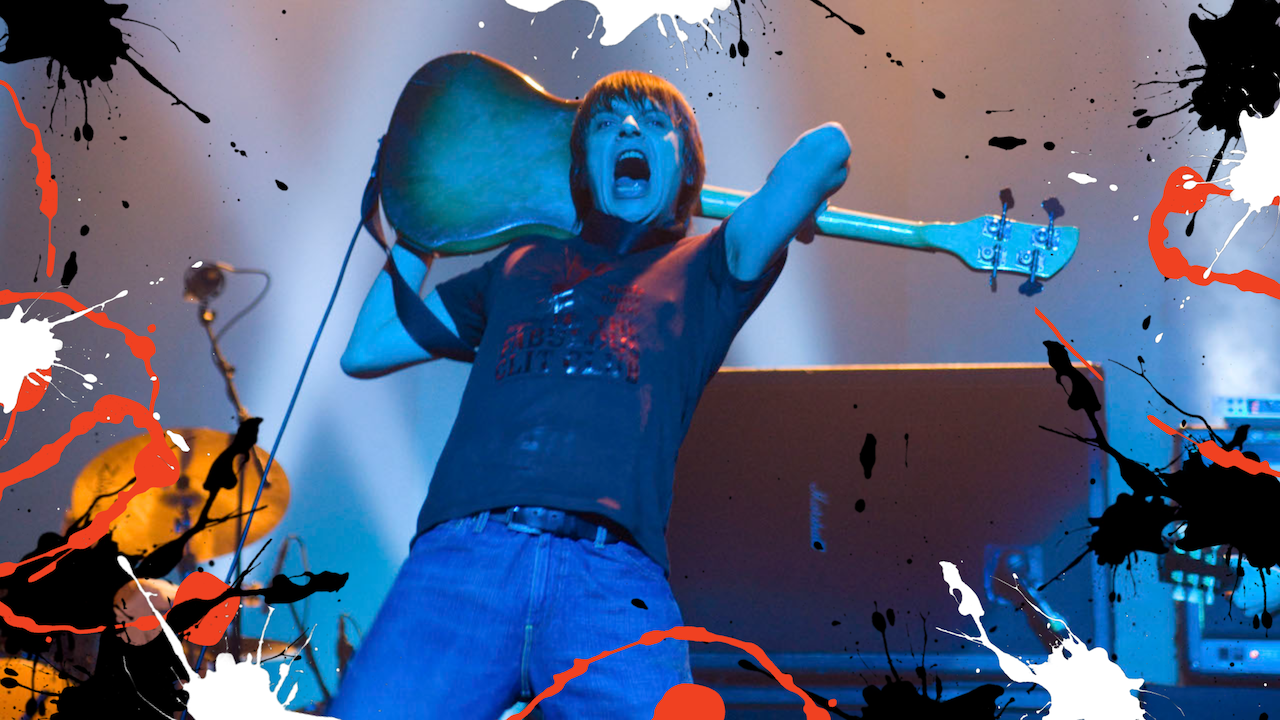

In 2010 he formed the short-lived Freebass with former Smiths bassist Andy Rourke and Peter Hook (Joy Division/New Order) and he stayed in Primal Scream until the Stone Roses reformed in 2011 – a reunion captured in the Shane Meadows documentary, The Stone Roses: Made of Stone. They released two singles in 2016 and played some festivals and huge gigs, like Wembley Stadium and Glasgow’s Hampden Park, the scene of their last show in 2017. In 2021 Mani appeared on a podcast by former Manchester United player Brian McClair where he suggested his touring days were over: “I don’t see myself being on stage anytime soon, to be fair.”

He’d made his money, he suggested, and his new hobby was fishing. “I just love fishing man. I like a bit of fluff chucking these days, now that I’ve moved into the genteel set. I like a bit of fly-fishing now. I enjoy getting out and emptying my head and communing with nature. It’s a good excuse to go to the pub after, too.”

We’ll miss him if it’s true. Back in 2000, he was playing with other people and loving it. "I've done a bit of freelancing recently,” he said. “We were never into collaborations an' shit [in the Stone Roses] and now I find it's really fresh and there's always something to learn from other people.

“I'm still learning. You can never know everything. I know fucking nothing, man, but ignorance is bliss, y'know what I mean?"