More than 20 years ago, every American was close to getting a free taco if a piece of a Russian space station hit a target in the Pacific Ocean.

After an uncrewed supply vessel crashed into Russia’s Mir space station, causing it to leak air and destroying one of its solar arrays, Russia eventually brought the space station out of its orbit. At the time, the space station was the largest object ever to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere, and people were anticipating its return.

In March 2001, Taco Bell set up a floating 40-by-40 foot target in the South Pacific Ocean that eloquently read, “Free tacos here.” The famous restaurant chain promised United States citizens a free taco if a piece of Mir hit its target.

Taco Bell estimated that giving all 281 million Americans a free taco would have cost about $10 million. But unfortunately, the stunt did not pan out as Mir’s disintegrated parts missed the target.

Lisa Ruth Rand, a history professor at Caltech who is writing a book on space junk, says that while the Taco Bell target was a miss, controlled reentry of deceased spacecraft into the atmosphere and dumping them into the Pacific Ocean is quite common.

“There have been plenty of spacecraft that have landed in this kind of satellite graveyard in the Pacific,” Rand tells Inverse. “But that requires a controlled reentry, rather than something falling based on the whim of physics, solar energy, friction, and where it’s moving through orbit.”

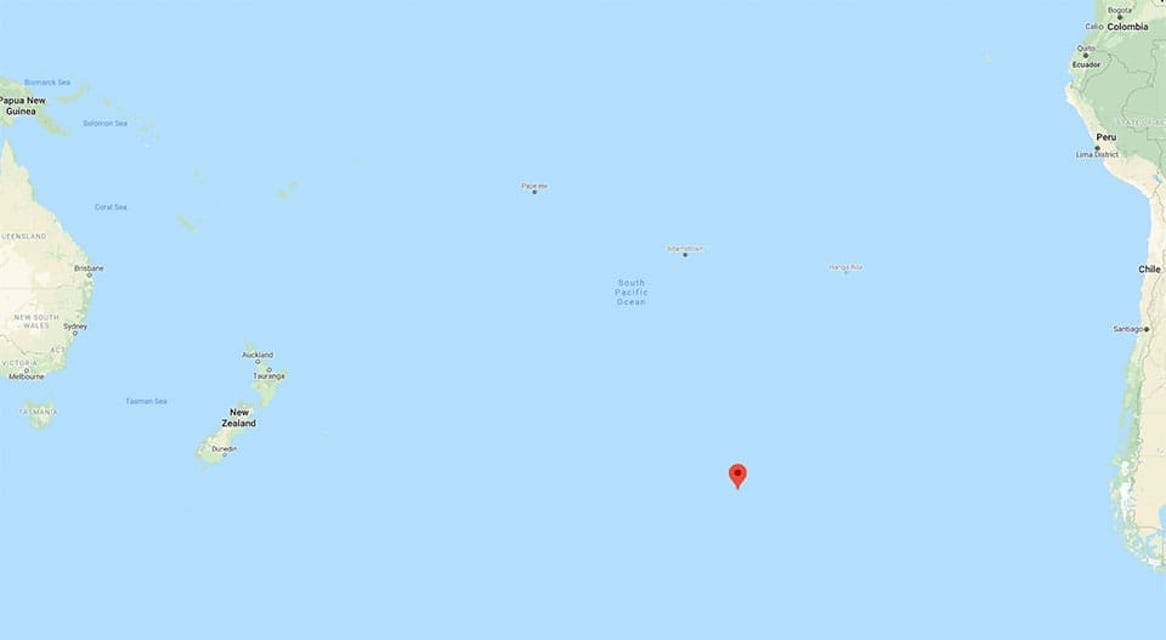

Last week, NASA announced the retirement of the International Space Station (ISS) by the end of 2030. After floating in near-Earth orbit for nearly 30 years, the ISS will plunge into a remote region of the Pacific Ocean known as Point Nemo, which lies between New Zealand and South America.

This area is fittingly known as the spacecraft cemetery, as the United States, Russia, Japan, and Europe have used it to dump some 263 pieces of space debris since 1971. Point Nemo was chosen by these nations because it is far from human habitat and is within the South Pacific Gyre. This current prevents nutrient-rich waters from filtering through the region, limiting the life that can call it home.

The ISS will be the newest addition to the cosmic corpses at Point Nemo, but certainly not the last. The space wreckage lays at the bottom of the ocean, with no plans to retrieve it.

“It’s not perfect, but it is actually right,” Rand says. “It’s responsible because it would be removing a collision hazard.”

Dumping spacecraft in a remote part of Earth’s ocean reduces debris in space. After satellites and other spacecraft are no longer of use, they are left to float about in the depths of space unattended.

Right now, more than 23,000 pieces of debris larger than 10 cm are known to orbit Earth, according to NASA. Re-entering a spacecraft through Earth’s atmosphere also helps break it up into smaller chunks.

“We are very fortunate that our atmosphere does a lot of cleaning up work for us,” Rand says. “They burn up because we have all this friction and pressure in the upper atmosphere that breaks things apart.”

And even then, it’s not all up to the atmosphere. Space agencies carefully calculate where to de-orbit a spacecraft so that it re-enters Earth’s atmosphere at a remote spot, reducing the chances of space junk hitting someone on the head.

When the first U.S. space station Skylab decayed and disintegrated into Earth’s atmosphere in 1973, scattering debris across the Indian Ocean and Western Australia, NASA calculated there was a 1 in 152 chance of the spacecraft’s debris hitting people on the ground.

Thankfully, the odds favored people’s heads, and there were no reported injuries.

So far, there has only been one case of a woman getting hit by a piece of space junk. In 1997, a defunct NASA satellite plunged into Earth’s atmosphere with a 1 in 3,200 chance of hitting someone. Unfortunately, that one chance was Lottie Williams from Tulsa, Oklahoma, who was hit by a piece of the Delta II rocket while walking through a park.

So while discarding defunct spacecraft by aiming them at remote parts of the world is best practice for now, it’s not always perfect, especially as space agencies send more satellites and orbiting spacecraft into space.

Therefore, sooner or later, the space industry will have to think of a new way to dump their discarded parts.

“Chances are, things everything is going to be fine, but I do think it’s worth thinking about,” Rand says. “As we send more things flying, thinking about how to carefully dispose of them and that space is a place that’s not always cooperative.”