You might have heard the phrase “social determinants of health”. It’s the idea that social factors – such as poverty, access to education, where you live and whether you face discrimination – have a huge influence on your health and life expectancy.

These determinants explain why worse health outcomes persist for some groups of people, despite incredible advances in medical care. This understanding has helped improve health policy in Australia and overseas.

We wanted to explore that idea in relation to incarceration. That is, to quantify what social factors increase a person’s chance of ending up in prison, and to use that to improve policy and reduce the harms and costs of incarceration.

Because while crime rates are decreasing and governments have committed to reducing reoffending, the incarceration rates of certain groups of people remain shamefully high. These groups include Indigenous people, those with mental and cognitive disability, and people experiencing addiction and homelessness.

Our findings, published today, reveal a criminal “justice” system that is far from just.

Read more: Giving ex-prisoners public housing cuts crime and re-incarceration – and saves money

What we did

We analysed studies of a data set containing information on 2,731 people who have been incarcerated in NSW.

The data comes from government agencies: NSW police, courts, corrections, and health and human services agencies such as housing and child protection. The data set is longitudinal. That means we can see the contact people had with services and institutions over time – from brushes with child protection services and police, to admissions to hospital and time spent in custody.

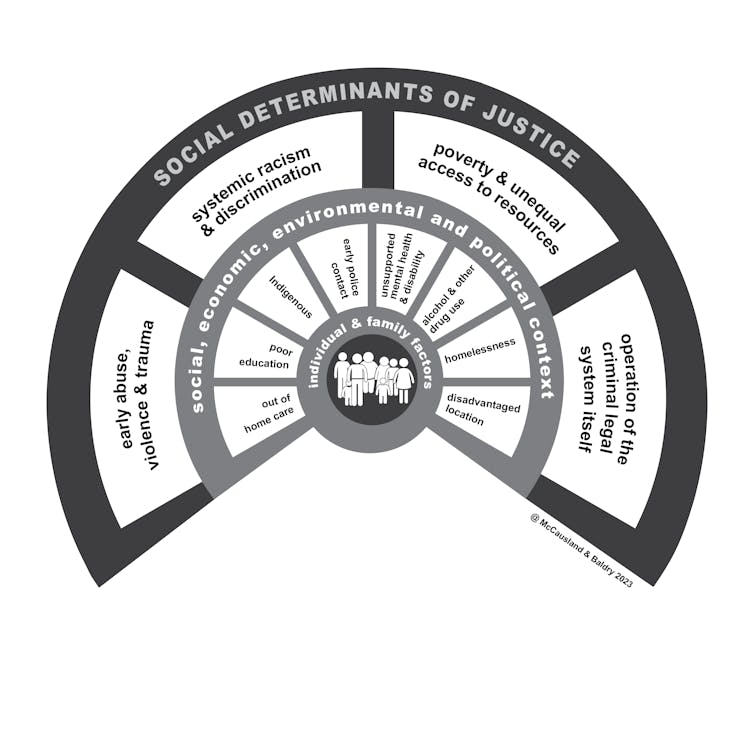

We identified eight factors as “social determinants of justice”. Our analysis showed that your chance of ending up in prison is greatly increased by:

- having been in out of home (foster) care

- receiving a poor school education

- being Indigenous

- having early contact with police

- having unsupported mental health and cognitive disability

- problematic alcohol and other drug use

- experiencing homelessness or unstable housing

- coming from or living in a disadvantaged location

And importantly, we found the more of these factors you experience, the more likely you are to be incarcerated and reincarcerated.

The people in our data set are often in custody on remand (not yet sentenced) and for minor offences, going in and out of the system on a criminal legal conveyor belt. This damages lives and doesn’t make our communities safer long term.

Why these factors?

We know from decades of work on the social determinants of health that our health outcomes are greatly affected by our social and economic context.

People working in this area have developed the concept of the social determinants of health inequity. Poor nutrition can contribute to chronic disease, but we’ve learned it doesn’t help to just tell people to eat healthier food because there are many barriers to being able to do that. Policy needs to focus on making nutritious food affordable and accessible to really make a difference.

For justice outcomes, there are also structural factors at play. For example, a person with cognitive disability who grew up in a middle class family with access to early support is very unlikely to go to prison, even if they are involved in offending. They have greater access to social advantages than, say, an Aboriginal person with cognitive disability from a remote town that has many police officers but few social services.

We can see from government data how many people end up in youth and adult detention after child protection, education, disability and health services fail them. Activists and advocates from racialised and disadvantaged communities have been speaking up about this for many years.

All this highlights that we need broader system and policy changes to reduce the unacceptable social and economic costs of incarceration.

We have further developed the concept of the social determinants of justice to identify the “causes of the causes” of who goes to prison. These are:

entrenchment of poverty and unequal access to resources in families and neighbourhoods

structural racism and discrimination, in particular experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and people with disability

failure to adequately respond to the abuse, violence and trauma experienced by so many children and young people

operation of the criminal legal system itself in the way that it is criminogenic; that is, it increases rather than reduces the likelihood of future incarceration.

The social determinants of justice show up in the over-surveillance of certain communities, lack of access to well-resourced legal representation, not being granted diversionary options and bail, and limited specialist services and support.

What now?

To really make a difference to one of the most pressing policy challenges in Australia – the shamefully high rates of incarceration of Indigenous people and those with disability and mental health issues – we need to focus efforts and resources on addressing these social determinants.

To truly reduce the harms and costs of incarceration, we can’t just roll out behaviour-change programs in prisons. And we can’t just focus on what police are doing or what happens to people in court – though these are important.

As well as a major overhaul of the criminal legal system, we also have to make sure other government agencies and non-government organisations are being held accountable; that people are getting the services and support they need before they end up in prison.

The social determinants of justice could inform policy to ensure police are not the frontline service for people in crisis.

It could lead to changed government procurement processes that recognise the value of Aboriginal community-controlled organisations providing culturally led support.

It could guide a holistic case management model for people at risk of contact with the criminal legal system. It could be used in evaluating a diversion program to inform improvements.

It could inform a whole-of-government approach to enabling people to thrive in their communities instead of wasting lives and billions of dollars through incarceration.

Ruth McCausland receives funding from the Paul Ramsay Foundation and NHMRC and is affiliated with the Community Restorative Centre.

Eileen Baldry receives funding from the Australian Research Council. She is affiliated with the Justice Reform Initiative.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.