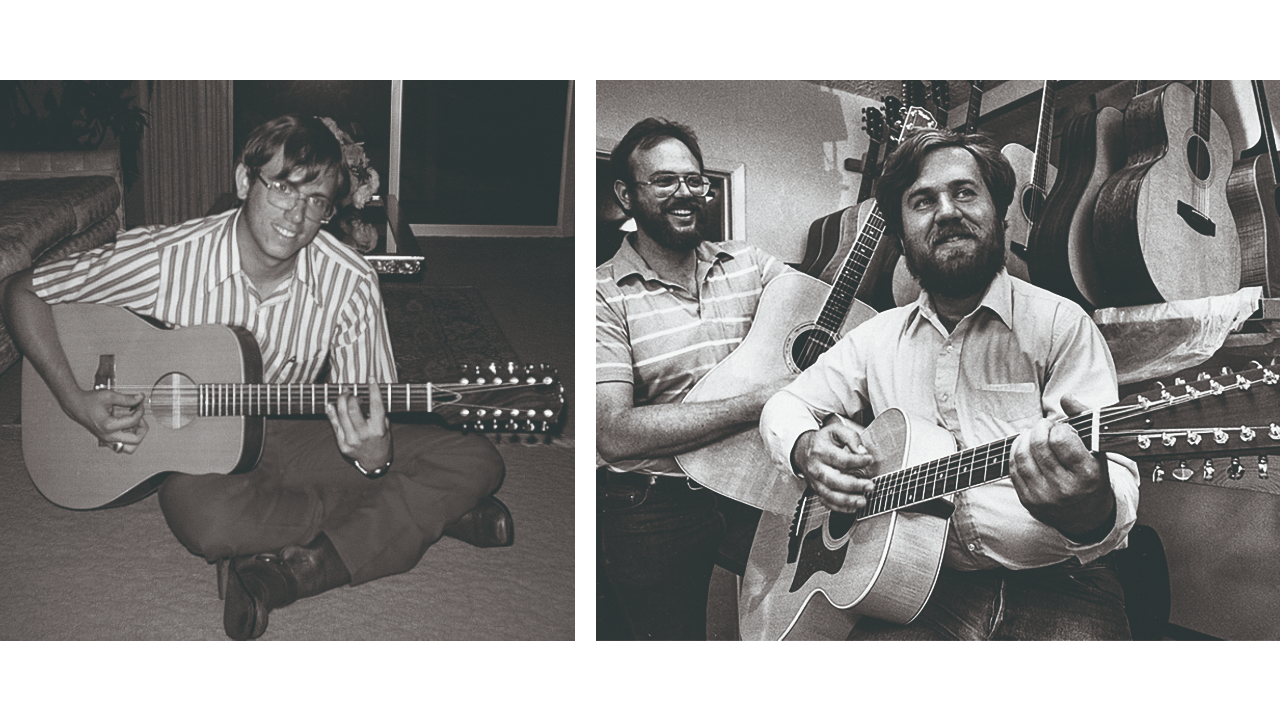

“When I was a young teenager, I loved the idea of playing guitar. At the same time, I was learning how to make things in school shop classes…” says Bob Taylor, co-founder of Taylor Guitars. “In my 11th grade high school woodshop class, I made my first guitar as a solo project. I was hooked and never thought again what I’d do with my life. It was settled in my mind.”

And so it was that the seed was sown and a life in guitar making was set. It all began in 1973 when Bob took a job at the American Dream music shop in San Diego, owned by Sam Radding. One year later, Sam was set to sell the business and Bob grouped together with his co-workers Kurt Listug and Steve Schemmer to buy the business.

Initially, they renamed it the Westland Music Company, changing to Taylor Guitars two years later. Since then, Taylor guitars have found their way into the hands of some of the world’s finest players and the brand has become synonymous with the highest-quality instruments available today.

In 2011, Andy Powers joined the company as master guitar builder, introducing new body shapes and, most importantly, the revolutionary V-Class bracing in 2018.

“Growing up as a guitar enthusiast in San Diego, it would be impossible for me not to feel admiration for Taylor guitars,” Andy, now CEO of the company, tells us. “Initially, like many other players, I appreciated the slimmer neck-carve style and low string height, as those fit my then-small kid hands. I was playing a lot of electric guitar then, so a Taylor neck and setup felt like familiar territory.”

To celebrate the 50th anniversary, Taylor has released a number of special models, including the 814ce Builder’s Edition. Here, we sit down with Bob and Andy to talk about the changes both the company and the industry have seen over the past half‑century.

Most contemporary guitar manufacturers employ some elements of automation in production today. What benefits do you think are passed on to guitar players by this ‘new’ technology?

Andy Powers: “From a broader perspective, the accuracy, consistency, dependability, and relative affordability of an instrument made with these modern tools is undeniable. Sure, as both a musician and a builder, coming to the craft of guitar-making from a traditional handcraft approach, it pleases me to sharpen my chisels and set them to a piece of wood. While great instruments can be made using traditional tools, the scale they can be made at is very small.

“The scale at which great guitars built with extraordinary accuracy can be made using modern tools is astounding, and musicians benefit from that. If that sounds like making good guitars has become easy because we have great tools; I can assure you, it’s not. It’s a huge challenge to design and implement machines, tools, and processes to create instruments. But what a fun challenge!”

Bob Taylor: “I love factories. And in the same way good cars come from factories, so do bad cars. It isn’t the idea of whether or not a factory is a legitimate way to make something or not – it all boils down to what kind of factory it is. We’ve built a good factory to make good guitars. I’m constantly defending the idea that guitars don’t have to be ‘handmade’ on a bench to be good.”

Which parts of the building process are still done by hand at Taylor?

Powers: “Much of the work that goes into a guitar is still done by hand. There are a lot of aspects in instrument making that are subjective and need a decision. From where in a board should a guitar back be cut? What sides best match this back? What is the best way to stain this sunburst?

“Any task requiring a judgement call inherently is handled by a person trained in that area. Other tasks requiring a combination of finesse, judgement and complex motion are handled by hands: applying binding and purfling work, installing rosettes, sanding, finish, shaping…”

Taylor: “All these things that Andy cites are accurate. Again, I will make the analogy of a car factory. If you visit the BMW factory in Munich, you’ll see almost nobody in the area where they stamp body parts. And the closer the car gets to completion the more people you’ll see. In the end, you’ll decide on your own that the cars are handmade.

“There’s an ocean of people making the car, even though there’s some crazy automated operations along the way. The Taylor factory is that way. It’s only natural. Probably 80 percent of the guitar is done by a person. The other 20 percent is done by a person using a fancy machine.”

You’ve championed the use of ‘new’ tonewoods in your guitars – like Urban Ash, for instance. How hard has it been to draw guitarists away from the mindset that only the traditional woods are good enough in their instruments?

Powers: “Any time a person sees something different from what they’re used to, it’ll be met with some level of skepticism. That can be a little bit of a challenge, in the same way that convincing a child to try an unfamiliar food can take some time.

“Often, the experience of playing the instrument and auditioning it on its own merit is all that it takes to change the mind of a player. That tends to happen one player at a time, and therefore requires a lot of building, playing, and time to gain broad acceptance in the music community.”

The V-Class [bracing] design isn’t hard to recognise as a synthesis of flat-top, archtop, mandolin, and classical guitar designs

Andy Powers

Taylor: “I like Andy’s analogy of teaching a child to try something different. To add to that, if it’s 100 kids, some of them will like it without question. Since we’re not making every guitar using Urban Ash, we don’t have to work too hard to convince everyone. Just offer it and there will be those who love it.

“In the case of Urban Ash, we’ve had pretty good success. On the other hand, maple has been used for centuries and is one of our favorite woods, yet we have to put a lot of effort into helping people give it a fair chance. It’s a wonderful wood, it sounds great, it’s available, it has a rich history, and we work hard to tell this story. Go figure.”

Taylor’s ecological awareness has resulted in its own supply of ebony. How did this come about?

Taylor: “Ebony came about when the Lacey Act made it clear that we had to really know how our wood was sourced. Two colleagues at our Spanish tonewood supply partner, Madinter – Vidal de Teresa and Luisa Willsher – presented to me an idea to partner up and buy an existing ebony sawmill in Cameroon. I said yes.

“We jumped off that cliff together and, boy, has it been a ride! We’ve learned so much. It even led to the launch of The Ebony Project, which is a non-profit managed by UCLA. We’re learning all the scientific data about ebony’s ecology as well as how to plant and grow it. I’m proud to say that it’s going well.”

Then there’s Taylor’s koa plantation, too.

Taylor: “One day, Chris Cosgrove, who purchases Taylor’s wood around the world, sent me a real estate ad for a large property in Hawaii advertising ownership of a koa forest. He said, ‘Maybe we should buy a forest!’

“I forwarded that to my friend Steve McMinn at Pacific Rim Tonewoods and posed the same question. Steve said, ‘I’ll find out.’ A month later he said, ‘Yes, good idea – but not that forest.’ And Paniolo Tonewoods was born. It’s a partnership between PRT and Taylor; we’ve since renamed it Siglo Tonewoods. We’re doing fine work there in Hawaii and planting a lot of koa trees.”

Possibly the most radical change in acoustic guitar design is your V-Class bracing, Andy.

Powers: “This idea arrived shortly after introducing our redesigned 800 Series in the winter of 2014. We’d nearly turned our factory upside-down in order to wring every bit of tone from the flagship guitar designs and finally got them into the hands of players. It occurred to me that we couldn’t go any further down the same development path without achieving only diminishing returns for our effort and therefore needed a totally different approach if we wanted to continue pursuing an ever-better guitar.

“Against that backdrop, I took some inspiration from a series of experiences around that time and applied those into what became the V-Class design, which in hindsight, isn’t hard to recognize as a synthesis of flat-top, archtop, mandolin, and classical guitar designs.”

Finishing has always been a controversial subject among luthiers, with nitro, acrylic, French polish, poly, and so on, all featuring in the debate. What are your feelings about the best finish for an acoustic?

Powers: “One common theme among all styles of finish material is that as the finish is made thinner, the differences between finish materials are less significant. If a finish is very thick, the difference between materials is even more apparent, and the damping factor is very high, to the potential detriment of the guitar.

“As the finish becomes thinner, you won’t hear as much difference between materials – simply because there’s less of it – and the damping the finish imparts is lower. Interestingly, low or no damping isn’t the greatest thing, either.

“An interesting experience is to hear a guitar with no finish on it whatsoever. That typically will have a brash, harsh sound as the inharmonious parts of a guitar’s vibration are not dampened away. Some vibration damping is welcome, even necessary, similar to the way a sensitive microphone needs a shock mount to isolate it from the vibration traveling through the floor or stand. Too much vibration isn’t good. Harmonic, musical vibration is.”

Taylor: “When every guitar maker used nitrocellulose lacquer, there was no controversy. When every guitar neck had a dovetail joint, there was no controversy. That joint only became argued to be the best when I bolted on a neck. Same with finish. Controversy started when Taylor dropped using nitrocellulose lacquer. My bottom line is, as Andy says, thin is best. Some is better than none. The rest is opinion, not fact.”

How do you feel about the practice of pre-worn or ‘relic’ finishes on acoustics?

Powers: “Aesthetically and philosophically, I tend to like what I describe as honest wear on a guitar, resulting from a musician’s use. I’ve seen some great examples of pre-distressed finishes, finishes intended to show wear quickly, but I most appreciate when a player takes the instrument, plays it all the time, and appreciates the story it tells as it ages.”

Taylor: “I’ve seen some great relic jobs on electric guitars. To me, it’s an art form. More power to them. To do it well is hard. To appreciate it is legit. It’s an art form that I’m not interested in doing on Taylors.”

Did the success of the American Dream Series come as a surprise? And are there plans to enhance the range still further?

Powers: “The success of the spartan American Dream guitars didn’t come as a surprise to me – musical inspiration has never been reserved exclusively for the luxurious instrument. Sure, a beautiful guitar with exquisite details is nice. Who wouldn’t love something lavish for a personal instrument to hold and play? But a great-sounding/feeling instrument is something that can transport a player into a dynamic experience, regardless of the sophistication of its ornamentation and trimmings.”

Taylor: “The timing was right. They came when our Tecate [Baja California, Mexico] factory was closed for Covid. We wanted people to have a guitar to buy in a price range they could afford. The design was very good. Thank you, Andy!”

There’s no doubt that the development of pickup systems for acoustic guitars revolutionised their use on stage, as it was pretty much a hit and miss affair previously. Taylor’s Expression System 2 differs from the typical under-saddle variety – could you talk us through that?

Powers: “The basis for this design was to use piezoelectric crystals to gather vibrational energy from the saddle and convert it to an electrical signal, but to do it within the natural dynamic range of piezo crystal. As piezo material is compressed, it becomes more polarised, and variations in the pressure will result in more or less polarisation. The material has an upper limit to how much pressure it can respond to, and downward string tension is commonly higher than this limit, overloading the potential dynamic output of the piezo.

“By placing the piezo behind the saddle and controlling the pressure, the piezo material can respond within its natural dynamic range for great detail in its output.”

Taylor: “Taylor designer Dave Hosler, now retired, conceived this design to do what Andy just described. It wasn’t easy to build. But we made a small factory to do it. I love the sound. Some people think of the saddle as bouncing up and down, but it really rocks forward and backward.

“This pickup senses that direction of motion, thus the tone is different from an under-saddle pickup. Imagine this: tie a rope to a wall. Stand back and stretch it tight with your hands holding on for dear life. Make it as tight as you can. Now have your friend pull the middle of the rope to the side. What happens to you? When he pulls, you move forward. When he relaxes, you move back. It’s how a string pulls on a saddle.”

With a notable resurgence in acoustic guitar music via folk, blues, Americana and so on, what plans does Taylor have for the future?

Powers: “Our plan is to continue doing what we’ve always done – build great instruments that fit the needs of musicians so they can continue to create music they and their audiences enjoy. It’s always a thrill to see musicians continue to evolve and develop their styles and repertoires, and we love building instruments to meet them along their musical journey.”

Taylor: “Our goal is to make guitars that are a pleasure to own and play. Guitars that come in different shapes, sizes and tonal flavors. Guitars that have good intonation and can play with modern instruments like electric keyboards with pure, accurate notes and also blend with all its normal stringed brethren.

“Guitars that can be adjusted and repaired since we already know they can have 100 birthdays and will need some love along the way. Guitars that can be your friend, whether you’re a Nashville cat, a Brit, or Vietnamese in Ho Chi Minh City, we want that guitar to hold up and help you tell your unique story.”

- For more info and the new collection commemorating the 50th anniversary of Taylor Guitars, see the company's official website.