This is not a women’s soccer story. This is not about the boys vs. the girls. This is a fútbol story.

This is a story that goes from dirt fields to world-record crowds, one about the planting of tiny seeds that sprouted to shatter glass ceilings. This is a story about dynasties and blueprints, about queens and pioneers. This is about the sacrifices that the next generation won’t have to make, and about being the hero you never had. This is a story about how a culture crafted a club, and how that club brought that culture to the world. This is the point where a revolution becomes a dynasty. But mostly, this is a story not about what soccer has lost, but about what it is gaining back.

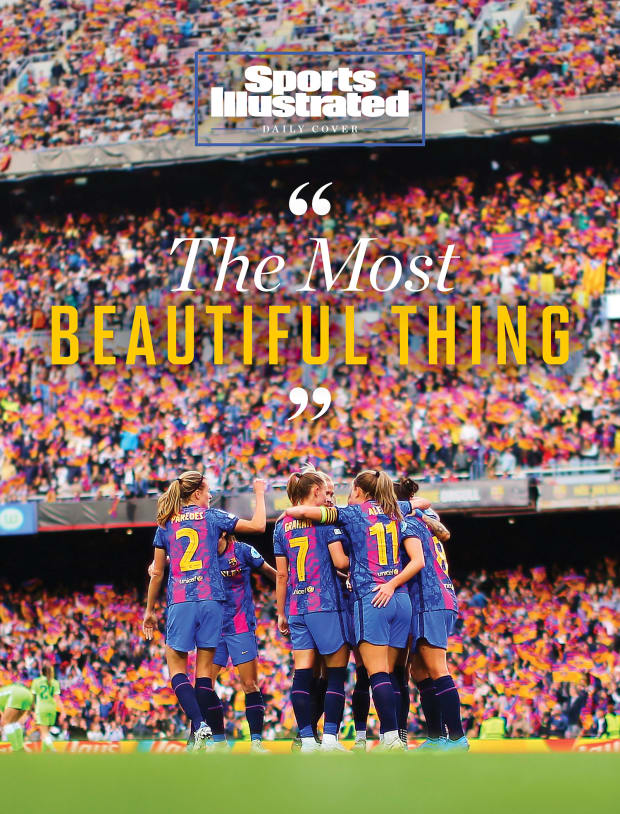

Or better yet, in the words of Alexia Putellas, one of the sport’s biggest stars, this is a story about realities so impossible that they could have never been dreams. It is, simply, about “the most beautiful thing that can happen to you.”

Eric Alonso/Getty Images

Fútbol talks in the streets of Barcelona. It cuts the air. After all, this is the territory of a dynasty.

As the most dominant soccer team anywhere in the world, Barcelona Femení is staring down a second straight UEFA Women’s Champions League title. Waiting in Saturday’s final in Turin, Italy, will be the original European women’s soccer dynasty: French power Lyon. It will be what Barça Femení manager Jonatan Giráldez calls “the perfect game in the perfect moment.”

Barcelona’s budding dynasty has been crafted as much by extraordinary individuals as by perfect moments, moments of wonder and rapture. If the club’s Camp Nou stadium is truly a cathedral of soccer, then March 30 was church, choir and communion. There is no other way to describe 91,533 fans watching Barcelona’s women destroy Real Madrid in the Champions League quarterfinals.

While Barça Femení plays most of its home games in the 6,000-capacity Estadi Johan Cruyff, the crowd at Camp Nou set an official world record for attendance at a women’s soccer game and surpassed the attendance for any men’s game this season. Leading the Femení into Camp Nou was their captain, Alexia. Like Madonna or Pelé, she is known by the gravity of one name, and she, too, is a star unlike anyone in her orbit.

Her face has popped up on posters and billboards across the city, and her jersey seems just as prevalent as Piqué’s or Pedri’s. It’s not just girls who wear them but boys of all ages rollicking down Las Ramblas, dribbling a ball through the crowds of bachelor parties and buskers. On the Barça website, her jersey is sold out in nearly every women’s size, and this year, the club started offering men’s sizes of the Femení jersey.

As a child, well before the Ballon d’Or and her Nike deal, Alexia religiously followed Barça’s men’s team. From her hometown of Mollet del Vallès in Catalonia, where a big screen has been installed to broadcast Saturday’s final, her family would often make the 30-kilometer trip to Camp Nou. From the stands she sang the songs and wore the shirt before they stamped her name on one. But this year, the crowds sang for her.

“I could have never imagined it when I was there as a kid,” Alexia tells Sports Illustrated. “And now it’s so beautiful because on top of everything, Barça has 122 years of history. And there are people who have come to matches at the Camp Nou for years who will tell you that they never had an experience like this. It was extraordinary.”

While the match unfolded on the field, the stands played host to a fiesta of epic proportions. Fans belted songs in Catalan and lifted color-coded tifos without a prompt, turning Camp Nou into a mosaic that could belong in Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia. The 90,000 sheets of color spelled out “More Than Empowerment.” And they were right: This was much more; this was power beyond measure.

Bildbyran/Imago Images

After the match, fans refused to leave; they continued on as if 90 minutes plus stoppage time wasn’t enough to contain the moment—because it wasn’t. This was half a century in the making. This was generations of women who worked second jobs, who endured the boorish abuse, who waited for the men to finish playing. The aura wasn’t just electric; it was transcendent.

“For a lot of places in the world, football is a religion—people burning their hearts out for it,” Barcelona winger Caroline Graham Hansen says. “And I think that’s one of the [things], especially for us, that is super, super beautiful. … Sports in general is about finding a place where you feel like you can belong.”

To say you were at the game is social currency in Barcelona, like bearing witness to a sort of Woodstock. Players, coaches and fans hardly mention the result (5–2 to Barça). Rather, they talk about the chills it still gives them, about being present for something they knew was both living history and the aspired future.

“I go to the stadium every week to see the men’s team and I don’t ever remember this feeling in the stadium,” Giráldez says. “Leaving there is one of the most special moments in my life.”

Less than a month later, they did it again for the Champions League semifinal vs. Wolfsburg. With another world-record crowd (91,648) the Femení was proving that this wasn’t a one-time event; it was the way forward.

Days after the first record-setting match, Barça made 50,000 tickets for the Wolfsburg game available for free to the club’s members, known as socios. The socios, who must pay a €195 ($205) membership fee each year just for the chance to then buy presale tickets to FC Barcelona matches, ate those tickets up by the end of the day. The next day, more than 35,000 tickets went on sale to the public for no more than €15. Those were gone in hours. Remember: Fútbol talks on the grand boulevards of Barcelona, and it turns out that word got around of a fiesta for the ages.

“When you do something new, and you like it, you want to repeat it,” Giráldez says. “And this is the most important thing, because it was created by human experience.”

After the Real Madrid match, you can see Alexia right where she belongs. Not just at Camp Nou or scoring goals, not just as Barça captain, but among the supporters. She applauds the crowd and sings their songs, and then commandeers a bass drum for herself and her teammates. While others struggle to find the rhythm, Alexia pounds with force, perfectly on beat because she knows the song’s twists and turns.

Her teammates call her La Reina (The Queen) because the actual Spanish queen snubbed the team when it won the Copa de la Reina last year. They placed a crown on Alexia’s head and bowed—part in reverence, part in jest—after her MVP performance. But to call her royalty would be to erase her roots—Alexia is a product of the region that made her, born by Catalonia and for Catalonia, tasked with taking it to the world. She is the icon needed to reinforce a dynasty. She is their patron saint.

Bagu Blanco/PRESSINPHOTO/Imago Images

For all this talk of queens and dynasties, true revolutions are not built by empires but by its citizens. As Femení general manager Markel Zubizarreta says, “Football has to meet a social moment.” Filling Camp Nou with more than 90,000 people—not once, but twice in a month—for a women’s soccer game is nothing but revolutionary.

When Barça officials and players talk about the moment, their eyes widen, childlike smiles crack through the façade of newfound fame. For the second time in this millennium, Barcelona is home to a soccer revolution.

Since the turn of the century, Barça’s men’s team has won 10 La Liga titles, seven Copas del Rey and four Champions League trophies. It boasted arguably the game’s greatest talent in Lionel Messi. Yet this season passed without trophies and Messi, but the culture was fertile ground for another dynasty to sprout.

“I think something that also helped us, which is maybe not good for the whole club but in terms of women's football, is that in the men’s side, they were not fighting for anything,” Zubizarreta says. “[In the end] the members, the fans, they want to enjoy and win.”

While fans may have come to win, they were also reminded of the community that they had lost, not just from a pandemic that left Camp Nou feeling haunted in its vast emptiness, but from a men’s game that has seen its sense of community commodified by corporate interest and stardom.

Eleven of the 21 players in the team that faced Real Madrid are Catalan—players who studied at Catalan schools, who grew up attending Barça matches, who took the regional trains to training sessions from their family homes. This is a connection that cannot be bought; it can only be forged.

Lluís Cortés would know. He is a former Catalonian national team coach and the manager who led Barça Femení to its first Champions League title last year. Cortés calls it a “mirror” effect, players performing in front of their neighbors and fellow Catalans who can see themselves reflected in the stars.

Joan Valls/Urbanandsport/Imago Images

“Catalan is very important because it’s the identity of the team,” Cortés says. “[The players] feel like Barça is their home, like they are the club, like it’s their own project.”

At the core of any revolution is a shared ethos, a communal fire that sparks the cause. Here, it is the Catalan identity. Players sometimes speak Catalan among themselves on the field to provide an extra advantage over other Spanish teams. Alexia says she speaks Catalan at home with her family and often does full press conferences in Catalan (English is next, she says in English with a bashful smile). Giráldez, the Femení team’s Galician-born manager, took Catalan classes immediately upon arriving in the region as a young coach, knowing the importance of the language.

FC Barcelona was born from this identity. In 1899, Swiss accountant and FC Zürich cofounder Hans Gamper placed an ad in a local newspaper looking to form a club during his time in the city. Today, the facilities where both the men’s and women’s teams train bear his name, albeit as Joan Gamper. The club’s founding father became so enamored with Barcelona culture that he adopted the Catalan version of his name.

The club’s famous motto is “Mes que un club” (More than a club), and it has proven itself throughout its history.

At the 17:14 mark of games, chants of “Independencia” can be heard throughout Camp Nou to commemorate the year 1714, when Catalonia lost its right to self-govern. In 2017, a Catalan referendum declaring independence was overruled by Spain’s constitutional court. Two years later, Catalan’s political leaders were jailed, and the clamor of the 17:14 chants has only increased since.

Under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco from 1939 to ’75, Catalan was banned from being spoken. Catalonia’s flag of independence was outlawed (its yellow-and-red striped flag, known as the Senyera, can still be seen in the Barcelona club crest). The period was seen as one of the darkest moments in the region’s history, but at the end of the Franco regime, the Catalan national team celebrated with a friendly at Camp Nou against the Soviet Union. Its star attraction was none other than three-time Ballon d’Or winner and Barça’s Flying Dutchman, Johan Cruyff.

The club became so associated with this identity that it became a sort of Catalan ambassador to the world. The men’s team’s success, especially over the last two decades, provided a window into a culture that may have otherwise remained in the northeast of Spain.

“Barça is a very important key factor for the strength of the Barcelona brand,” says Cortés, who now manages the Ukraine women’s national team. “Some people in Ukraine told me: ‘You are from Barça.’ No, Barça is not the city, Barcelona is, but people think that you are from Barça. Barça is just a club inside the city, but sometimes they think the club is in front of the city.”

Part of the beauty of seeing the sport bloom from its roots is seeing the movements it inspires. Multimedia outlet La Piña Informativa is the pinnacle of this. Upset by the lack of coverage of the women’s team, restaurant cook Gemma Gallego and Piña cofounder, Ramon Tena, bought a camera and started attending Femení youth matches.

For years, they have taken photographs and recorded full matches of every Femení youth team, all the way down to the under-12 team. Each video goes on YouTube and racks up thousands of views from around the world, from parents of players to fans of the game: “We’ve never charged anyone a cent for this,” Gallego says. “We work second jobs just to fund it. It’s my life.”

Meanwhile, the club broadcasts Femení games via Barça TV+. Barça Femení is one of four Spanish clubs that controls its own media rights, something that would be impossible in the men’s game. And for Champions League, DAZN live-streams the matches for free on YouTube, providing open access to millions to grow the game.

With 144,000 socios, more than 1,200 supporters clubs (known as penyas) and both official and unofficial channels to distribute to the masses, the infrastructure for a dynasty has already been established. Like ancient Roman walls, it just needed to change ownership—and now the Femení have moved in.

Before Barcelona Femení broke world records, before Alexia’s Ballon d’Or and an unprecedented undefeated league campaign—this season’s title was won with a 30-0-0 record as Barça outscored foes, 159–11—there was just a plan. Success on and off the field has since turned it into a blueprint.

Club officials and players all point to one decision that sparked the revolution: turning professional in 2015. Before the switch, Barcelona had won four straight Spanish league titles, but the conditions were poor. Players trained in the late afternoon and evening instead of the morning. Coaches of the youth squads were often fathers of the players. The club’s medical facilities were mostly off limits. Matches were held on artificial turf at the training ground where fans had to sit on concrete blocks behind one of the goals due to a lack of stands. But in ’15, all of that began to change.

At the forefront was Zubizarreta, the son of legendary goalkeeper Andoni Zubizarreta. He was hired as the head of women’s soccer management and has since become its GM. His first task was crafting a culture of professionals; his next task is “to always evolve.”

“We had really good players, but they were coming from a point of view of football that was nonprofessional,” he says. “So first of all, what we tried to do is build the staff that can make all these differences. Coaching, tactics, medical services, psychology, nutritionists, people from the press media. Anything we can do to have the environment so we can reach other levels.”

But the restructuring took time and patience, something of a luxury in the world of professional sports. The club went four straight seasons without winning the league and fluttered through three managers in less than three years. Zubizarreta admits that if he was the men’s team’s GM, he might not have been around to watch his plan unfold.

“We could make the decision that we think was the right decision—it doesn’t matter if we win or we lose. That’s freedom,” he says. It shows that when you build these kinds of projects with that kind of freedom, things happen.”

In 2019, the seeds planted four years earlier began to bear fruit. Midway through the ’18–19 season, Cortés was named as the club’s new manager just six months into his first season as a Barça Femení assistant. Within months, Cortés led the club to its first Champions League final.

Thiago Prudencio/ZUMA Wire/Imago Images

It turned out to be a devastating lesson. With a 4–1 defeat to Lyon in Budapest, the French giant proved just how far Barcelona had to go to reach its level, which at one point included five straight Champions League titles. But Cortés, like many of the team’s current stars, says it was that loss to Lyon that led to the second spark in Barça Femení’s professional journey.

What followed were more intense training sessions, greater emphasis on strength and conditioning (Alexia added 10 percentage points in muscle mass), commitment to a nutritionist who personalized diets and fitness tests and individualized video sessions after each game.

The result showed in a scorched-earth run last season that ended in a historic treble: a Spanish league title, the Copa de la Reina and its first Champions League trophy. The journey to the latter was done one way: the Barça way. “We have our identity, we have our DNA, and it’s something that we don’t [budge on],” Zubizarreta says.

That included appointing Cortés’s successor after the coach left last summer. Rather than search for a coach with pedigree, Zubizarreta opted for Cortés’s assistant in the 30-year-old Giráldez, who just last month suffered his first loss as manager.

Instead of looking to Lyon as a model of success, Zubizarreta says the club looked internally. While the Barça men’s team was an entity almost bigger than the sport itself, FC Barcelona also had handball and basketball teams that provided Zubizarreta with an example of a parallel structure within the club’s philosophy for things like training regimens and contract structures. The club also had its famed La Masia academy, which had helped produce the likes of Messi, Andrés Iniesta and current Barcelona men’s manager, Xavi.

“There was one point of view that was, ‘We can increase the budget, try to sign the best players in the world and win [now],” Zubizarreta says. “We said, ‘No, we have our own point of view.’ We believe in a way of playing football. We believe in a way of training. We believe also in a way of building the teams with players from La Masia.”

At the academy, three girls youth teams already compete in leagues with boys teams. This season was the first in which girls were admitted as live-in residents. The club refers to the nine youth players as “the pioneers,” and they are setting out to do what no Barça Femení player has done before.

“These girls are going to have much better conditions, better preparation and that, in the future, will be reflected in better entertainment,” Alexia says. “In the end, between boys and girls, your dreams as a footballer are the same, no?”

Bagu Blanco/PRESSINPHOTO/Imago Images

If there are Femení pioneers, then there must also be a pathfinder. In her 18th year with the club, Melanie Serrano has spent more than half her life playing for Barça Femení. No one still playing for the club has suffered relegation (2007) and then won a Champions League (’21). Few will remember training on dirt fields, working second jobs and taking 10-hour bus rides overnight to away games—unless you are on one of 39 fan buses headed to Turin for Saturday’s final.

At 32, she is in her final weeks as a Barça player before she starts in a new, undefined role with the club. When she was 14, she joined Barcelona a decade before it became professional. After school, she would rush to catch a 90-minute train from Blanes to old dirt practice fields outside of Camp Nou, which have since become a parking lot.

Serrano would then have to leave training early to catch the last train back to Blanes at 10:30 p.m. When she arrived home after midnight, her mother would often be away, working nights to pay for the train rides and the packed lunches.

She has, in essence, seen it all.

“It just so happened that Barça was in the same situation as me when I started: I was young and Barça [Femení] was nothing,” Serrano says. “We grew up together, the same steps the entire way. That is our shared story. … We began at the lowest part of the process and reached the top of the mountain.”

Barcelona Femení’s history is full of stories like Serrano’s. But the very first story, much like the club’s foundation, started with a magazine ad.

In November 1970, the 16 women who responded to 18-year-old Immaculada Cabecerán’s call formed Selecció Ciutat de Barcelona. Their first task: Prepare for a Christmas Day exhibition, which would take place in front of a near-capacity crowd in Camp Nou.

One of those players was Carme Nieto, a Barça diehard and longtime socio. A secretary for a pharmaceutical company, Nieto used all her vacation days to train with the new team, which was mostly made up of nurses and shop workers.

“When we first went out for training, the only thing we knew was that the ball was round,” Nieto, 74, says. “My only experience was playing soccer with my brother in the street.”

AFCB | Fons Carme Nieto

Nieto says the notion of women playing soccer was so discouraged that many of her teammates gave fake names so their families wouldn’t see them in the newspapers. The resistance to the team was so fierce that Nieto recalls seeing a doctor comment in the newspaper that women who played soccer wouldn’t be able to have children.

But when Christmas arrived, Nieto’s family came to support her in a crowd of roughly 60,000 fans. Goals were set at the penalty areas, and the halves were 30 minutes each, since it was a curtain-raiser to the Barça men’s friendly. Nieto’s team ended up winning on penalty kicks, but once again, the result was the least talked-about facet.

“That was the most beautiful thing I have experienced in my life. Lift your head out and see the stadium practically full. [After] that atmosphere, all those people, we said, ‘This cannot stop. We cannot stop.’ And we never left.”

Because the team wasn’t officially part of Barça (that came in 2002), it couldn’t sport the club’s crest and colors. They wore secondhand, white long sleeves that belonged to the men’s team and, only after pressuring club officials, were allowed to wear Barça-striped socks.

“I said, ‘I am here, and I want to play here where my team plays, where my players play. … We have to wear something from Barça. It can’t be that we’re going to play on this field and won’t be wearing the colors,’” Nieto says.

Nearly 52 years later, Nieto sat in a box at Camp Nou with some of her former teammates. This time, the women’s team wore the club’s crest and colors. This time, they were the main event.

“We hugged and cried to see the colors, the people with flags,” Nieto says. “Ninety-one thousand spectators—what a beautiful show. ... I am proud to say that I was a pioneer of Barça. It’s as if it were royalty. The duke, the king, no, I am a pioneer of Barça.”

FC Barcelona | Seguí

There is one more match before the crown can lay firmly on Barça Femení—and it’s being hailed as the biggest women’s soccer match in Europe’s history.

Lyon, winner of seven of the last 11 Champions League finals, boasts the competition’s all-time leading goalscorer in Ada Hegerberg (58 goals in 59 games). And while Barcelona has dominated the sport over the last two seasons, Hegerberg reminded the world about the Lyon dynasty that still exists: “There was women’s football before Barcelona, and it was played here for years,” she told L’Equipe last month.

“I think it hurts [Lyon] a bit that everybody recognizes us as the best team in the world, or even of history,” says Graham Hansen, Hegerberg’s Norway teammate. “We never said anything about it. We know that if we want to ever become better than them as the world’s best club in history, then we have to start winning more than one Champions League title.”

The final will feature two Ballon d’Or Féminin winners in Alexia and Hegerberg (Megan Rapinoe is the only other woman to win the award). That alone will be worth the price of admission, but the true battle lies in one dynasty trying to protect its legacy, and another trying to craft its own.

“We have the example that Lyon won it seven times,” Alexia says. “It will always be a nice challenge to try to achieve that, although we know that it’s really complicated because it is very difficult to repeat. But there will always be that challenge, and then also the challenge of continuing to write our own story.”

But as Zubizarreta says, there is a certain kind of freedom in knowing that the club’s trajectory will continue regardless of Saturday’s result. There is too much on the horizon, too much of the frontier yet to explore.

In 1970, Cabecerán’s trailblazing ad began with the words: "Women's football is making its way. And it is coming to Barcelona.” Now the question is what happens when the rest of the world makes its way to Barça? That may be the most demanding challenge yet for a dynasty, its queen and its pioneers.