Some of the earliest examples of art feature the human body – our own appearance has always fascinated us. From early, stylised representations of the female figure found in Paleolithic art to true-to-life depictions of specific people in busts, statues and portraits throughout the ages, we have always made paintings and sculpture in our own images. Some of the most iconic examples of Western anatomical art come to us from Ancient Greece, and from the Renaissance that the rediscovery of the Greek aesthetic inspired.

If you're interested in starting your anatomy drawing journey, check out these 12 tips for drawing the body, and why not take a look at our picks for the best drawing tablets, to get you set up for success.

Early anatomy in ancient Greece

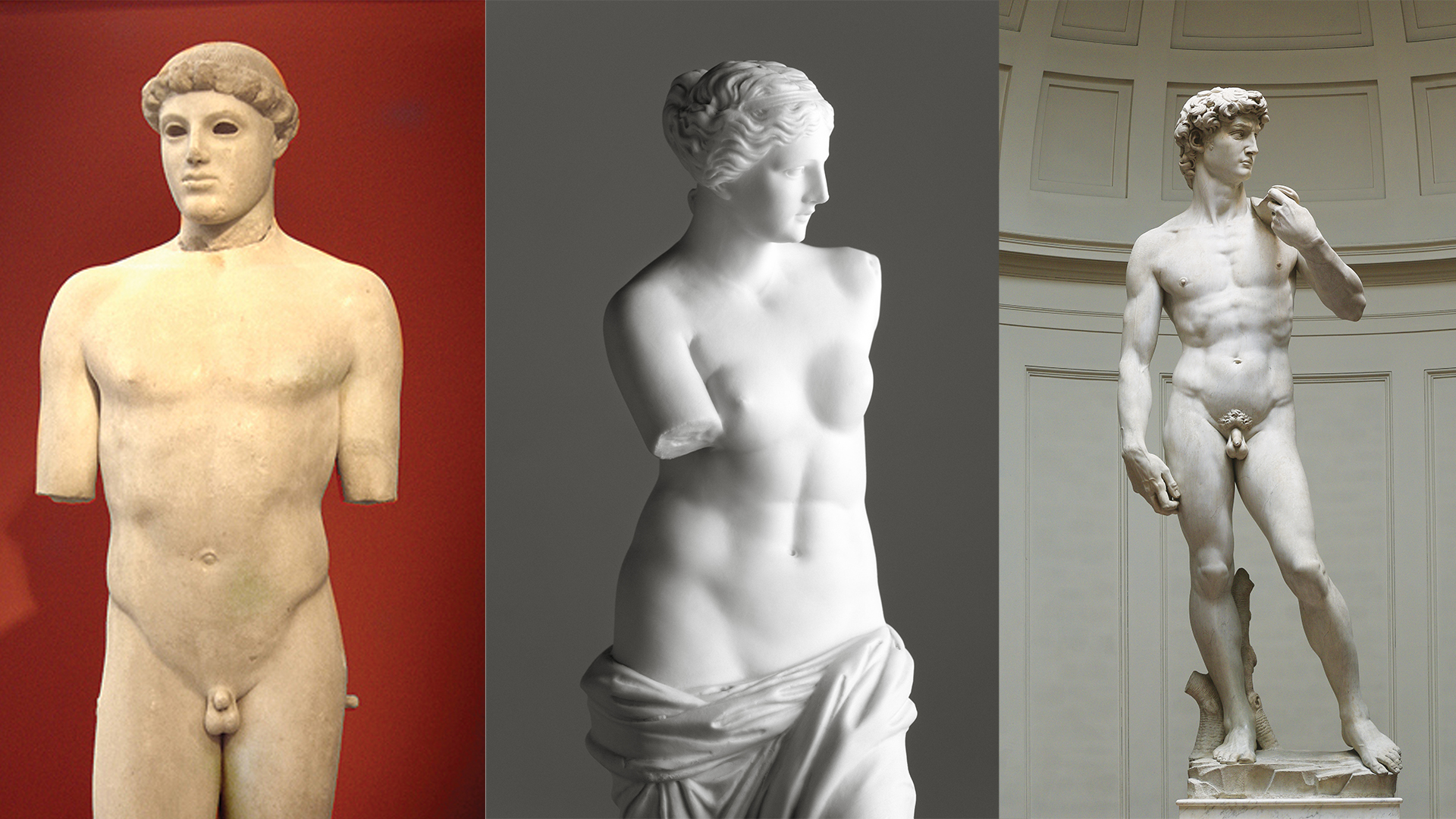

Ancient Greece, with its patriarchal societies and emphasis on martial and athletic prowess, developed an artistic focus on the human figure, particularly the male figure, during the Cycladic culture of the Bronze Age. These sculptures are stylised and static, standing in a foot-forward pose that despite its posture still seems frozen and immobile.

These kouroi (singular, kouros – the word means ‘boy of noble rank’) that were sometimes thought to depict the god Apollo were ubiquitous across Attica and Boeotia – there were over 100 found in a single temple of Apollo – and were mostly sculpted in marble, but other materials included bronze, wood and limestone.

These statues are usually life-size, standing between five and six feet tall, but some were colossal in scale, rising over three metres. It’s impossible to imagine that these larger ones were not depicting a god, and indeed their female equivalents, called kore (‘maiden’), take their name from one of the pseudonyms of the Greek goddess Persephone.

These female sculptures, however, are depicted clothed in column-like robes and with secretive Mona Lisa smiles that represent a stylised ideal rather than an accurate representation. And Greek artists weren’t satisfied with that – they wanted to create sculptures that appeared to be energetic images of idealised humans and gods.

By the 5th century BCE, Greek sculptors had begun exploring a new idea, one that allowed them to express energy and movement even in heavy, carved materials. The idea grew out of the one-foot-forward pose of the kouroi, and is known to us by the name given to it by the artists of the Renaissance who rediscovered it: contrapposto.

The word means ‘counter poise’ and describes a stance in which the figure rests most of its weight on one foot. Stand in this position yourself and you’ll notice that your shoulders and hips skew and slouch: your arms don’t hang straight and flat by your sides but find a more mobile or relaxed pose, with hands on hips or waist, or swinging freely. Your waist and hips are placed at an angle rather than parallel to the floor thanks to the stance of your legs.

A contrapposto pose speaks of both relaxation and energy, as the figure appears to have been caught in the moment of movement, or just before or after. This is called ponderation, the body caught between stillness and walking. The engaged leg – the one that takes the majority of the weight – bears the load of the sculpture, making it as solid and sturdy as the kourai but a great deal more visually dynamic.

This can be seen to great effect in the Kritios Boy, the first sculpture extant known to have used contrapposto. While the figure has a lot in common with the solid, tense kourai – the faint smile, the arms by his sides (although we don’t know what position his missing forearms were in, it seems likely from the pose of the remaining sculpture that they followed the line and position of his upper arms) – his waist, and the changes in posture its position causes, became a revelation in Western art.

Slack, relaxed, almost slouching, the left side of his pelvis is pushed higher than the right by his pose, making his right leg relax and his spine curve into an elegant S shape. Stand in an easy, comfortable pose while chatting and you’ll find that you adopt a similar stance. Unlike a mute and awkward straight-up statue, a contrapposto pose is flexibly, warmly, lightly and unmistakeably human.

Other aspects of the Kritios Boy are more subtle in their naturalism. Unlike the solid kouroi, the Kritios Boy’s ribcage is expanded, causing the musculature of his torso to shift and stand out – this is stone that has been caught in the act of breathing. And despite his kouroi-like expression, his face, and particularly his lips, are more meticulously observed and rendered than that of previous ancient sculptures. The statue has an expression, although admittedly it is a reserved and faintly bored one. But the expansion of this style became anything but boring.

Contrapposto and composition

One of the greatest ever examples of contrapposto from the ancient world was rediscovered in 1506. Excavated in Rome, before it was lost it was written about by one of Rome’s most prolific writers on art, Pliny the Elder, who claimed that the sculpture was the work of three Greek sculptors from Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodorus and Polydorus.

Unfortunately he didn’t record when they made the sculpture, who it was for, or whether it was a copy of an older Grecian work. This is a shame, as Laocoön and His Sons is one of the most magnificent sculptures of the ancient world that is still extant today. It’s a virtuoso performance in stone that sees the contrapposto technique elevated to its visceral, emotive height.

The sculpture tells the story of the Trojan priest Laocoön, who together with his sons meets a terrible fate: bitten and poisoned by venomous serpents. In the various versions of the story, the father and at least one of his sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, perish. Some variations of the myth claim that the snake attack was to prevent Laocoön from exposing the Greek ruse of the Trojan horse, while others say that he offended a god – usually Poseidon, Athena or Apollo.

Whatever the cause, Laocoön’s painful, serpentine punishment convinces his besieged city to allow the Greek gift of a wooden horse inside the walls of Troy. By night, the Greeks emerge, slaughter the city’s men, take the city, and bring about the collapse of Troy and the end of the ten-year Trojan War. For the Romans, whose folklore claimed descent from Trojan refugees, the subject was a well-known tragedy, and this is represented in all its terrible glory in the sculpture.

The three male figures are hyper-realistic, their musculature over-emphasised by the contortions of physical and mental agony. Laocoön is depicted trying desperately to wrench the coils of a snake away from himself and his sons. One appears to have already succumbed to the venom; the other may possibly make an escape if he can untangle himself.

At just over two metres in height, the tableau is a touch larger than life-size, its proportions heroic rather than human. Yet, unlike the Kritios Boy, it’s not naturalistic. Notably, the scientist Charles Darwin visited the sculpture during the Victorian era and pointed out that, even with snake venom twisting his features, Laocoön’s wildly bulging eyebrows are so exaggerated as to be physically impossible.

The discovery of this sculpture changed more than just the history of Ancient Greek art, however – it also altered the future of both painting and sculpture. The 16th century was the age of the height of the Renaissance, the ‘rebirth’, when polymath artists went back to the art and science of antiquity and rediscovered its treasures. One of them, in fact, had been rediscovered as early as 1430, although it was largely ignored save for a study of its inscription – it’s signed by an otherwise unattested artist, an Athenian named Apollonios, son of Nestor.

The Belvedere Torso – at the time theorised to be the hero Heracles reclining on the skin of the Nemean lion, a legendary creature he killed as one of his 12 mythical labours – is a remnant of a classical statue that turned up in a cardinal’s art collection in the mid 15th century. Its importance wasn’t fully realised, however, until the discovery of Laocoön and his Sons. It has been remarked that it took a century for the Belvedere Torso to achieve the importance and recognition that Laocoön and his Sons garnered in a fortnight.

The two sculptures, despite the differences in their eras and regional styles, have some commonalities that captured the imagination of the Catholic Church, the biggest commissioners of art in Renaissance Rome. The Belvedere Torso is now thought to depict the Greek hero Ajax contemplating suicide, another story of the Trojan War. Both sculptures use contrapposto in order to physically represent physical and mental agony, although the Church saw their mythical themes as empty of spiritual pain.

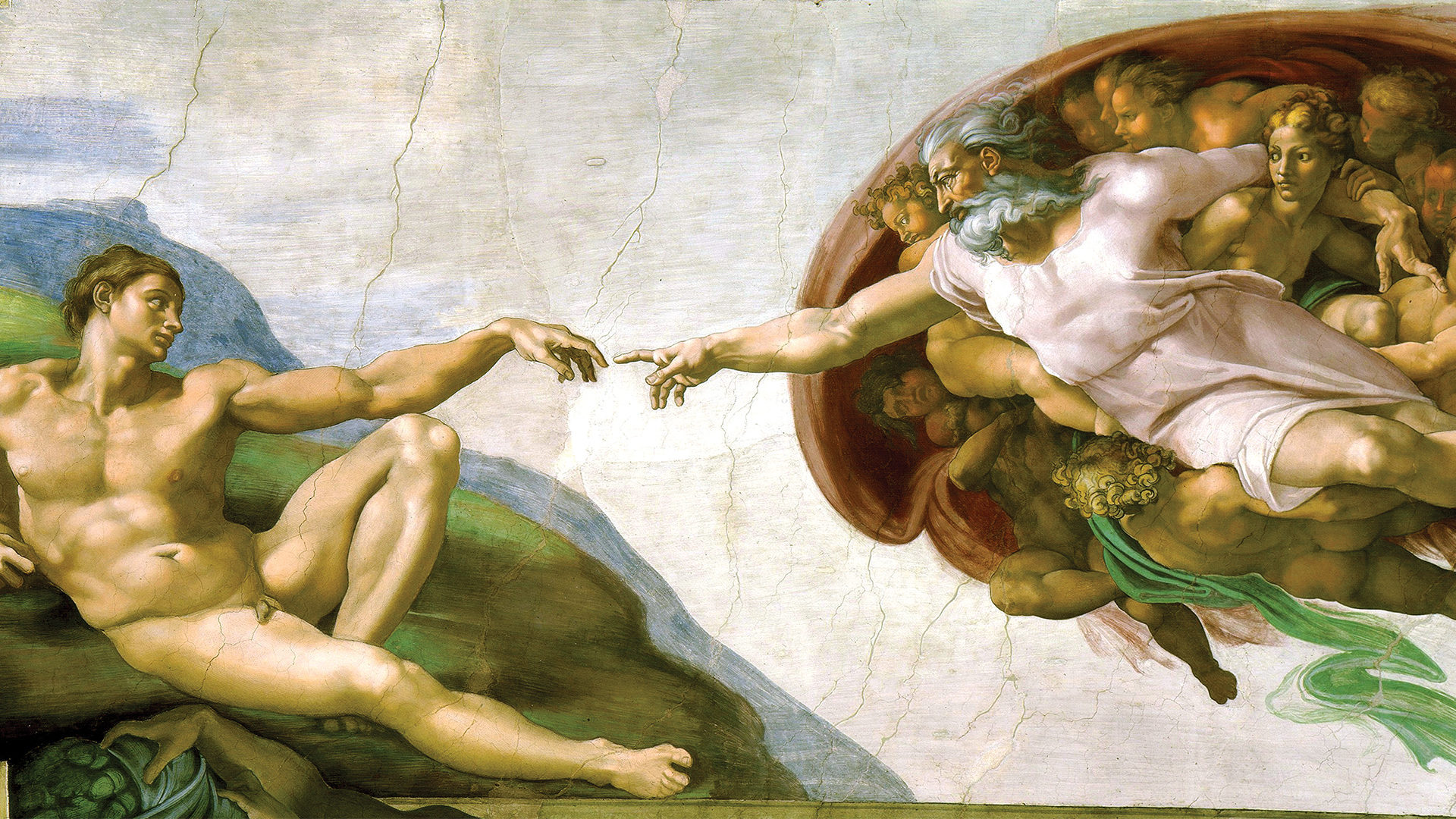

Anatomy and spirituality

For the Church, whose iconography showed hundreds of martyred saints as well as the suffering of Jesus Christ, the idea that art depicting the human form could explicitly allude to soul-forging suffering was a compelling one. It would grab the attention of the populace, in the same way as the sex and violence of shows like Game of Thrones capture attention today.

It would allow for the reappropriation of clever, beautiful, but pagan art styles and knowledge, and reroute their iconography into the ‘proper’ channels: the worship of God and the veneration of the saints. It would allow the Church to rebrand its stiff, millennialist, Medieval imagery into something suitable for a world that was starting to emerge into a new age. It would change the face of art forever.

Many in the Church had expected the Second Coming of Christ and the end of the world to occur not long after the turn of the first millennium. They hadn’t thought much beyond this, and indeed Medieval religious art is often packed with this waiting tension. As a consequence, the Church’s art style was decorative, stiff, wilfully incorrect anatomically, and old-fashioned. It felt out of place, and the Church didn’t want to represent its key figures as aloof, stylised or ugly any longer.

The creative exuberance and skill of the recently rediscovered ancient works posed both a challenge and a question. The ancient pagans had skills that seemed, objectively, to outstrip those of the later Christians, despite their adherence to what they thought of as the one true path. Could Christian figures be represented in the same way? Could an artist bring similar pathos and empathy to representations of the sufferings of Christ and his saints? Weren’t people much more likely to pray to and invoke a power that they saw represented as human, and yet more than human?

At the same time as Laocoön and His Sons was being unearthed from its hiding place in the vineyard of one Felice De Fredis on Rome’s Esquiline Hill, one of Florence’s most famous artists was working on a statue of this very nature. Michelangelo’s biblical David, the humble shepherd raised to kingship through the will of God, is elevated in more ways than one.

This is no Israeli rustic, nor plucky little giant killer – most viewers today barely register that the subject of the 5.17-metre statue is a hero and king of the Old Testament, because what they see is a beardless, beautiful youth in the classical, colossal Greek style, muscles delicately modelled, posed in a lively, insouciant contrapposto.

Most artists tasked with depicting David chose to show him at the end of the most famous tale about him – immediately after the defeat of the giant Goliath, with his enemy’s head at his feet. Art historians theorise that Michelangelo chose to depict the young hero before his victory, before the fight had even begun.

With his slingshot tossed lightly over his shoulder, the lithe David looks as if he is about to break into a run, to begin whirling the sling and let the bullet fly. He looks fleet-footed, strong and in the prime of youth. And yet, like Laocoön, he is impossibly imperfect. His head and hands – focal points of the image – are too large for human proportions, perhaps designed to draw focus, because he was originally supposed to be displayed on a rooftop and they were the most important parts of the sculpture.

Despite his appearance of strength he’s too slim, proportionally, for his height. Like many Renaissance sculptures, particularly by Michelangelo, his genitals are too small – perhaps referencing the ancient Greek aesthetic ideal of he beautiful pre-pubescent boy. There’s some socio-political snark hidden in his contrapposto pose, too.

As a motif, David is often associated with Florence, the artistic heartland of the Renaissance. When the statue on its 2.5-metre plinth was placed in the Florentine courtyard from which Roman authorities had taken a Donatello bronze of the same subject years previously, during the exile of Florence’s famous Medici family, David’s titled head and watchful glare throw some distinct side-eye in the direction of the Eternal City.

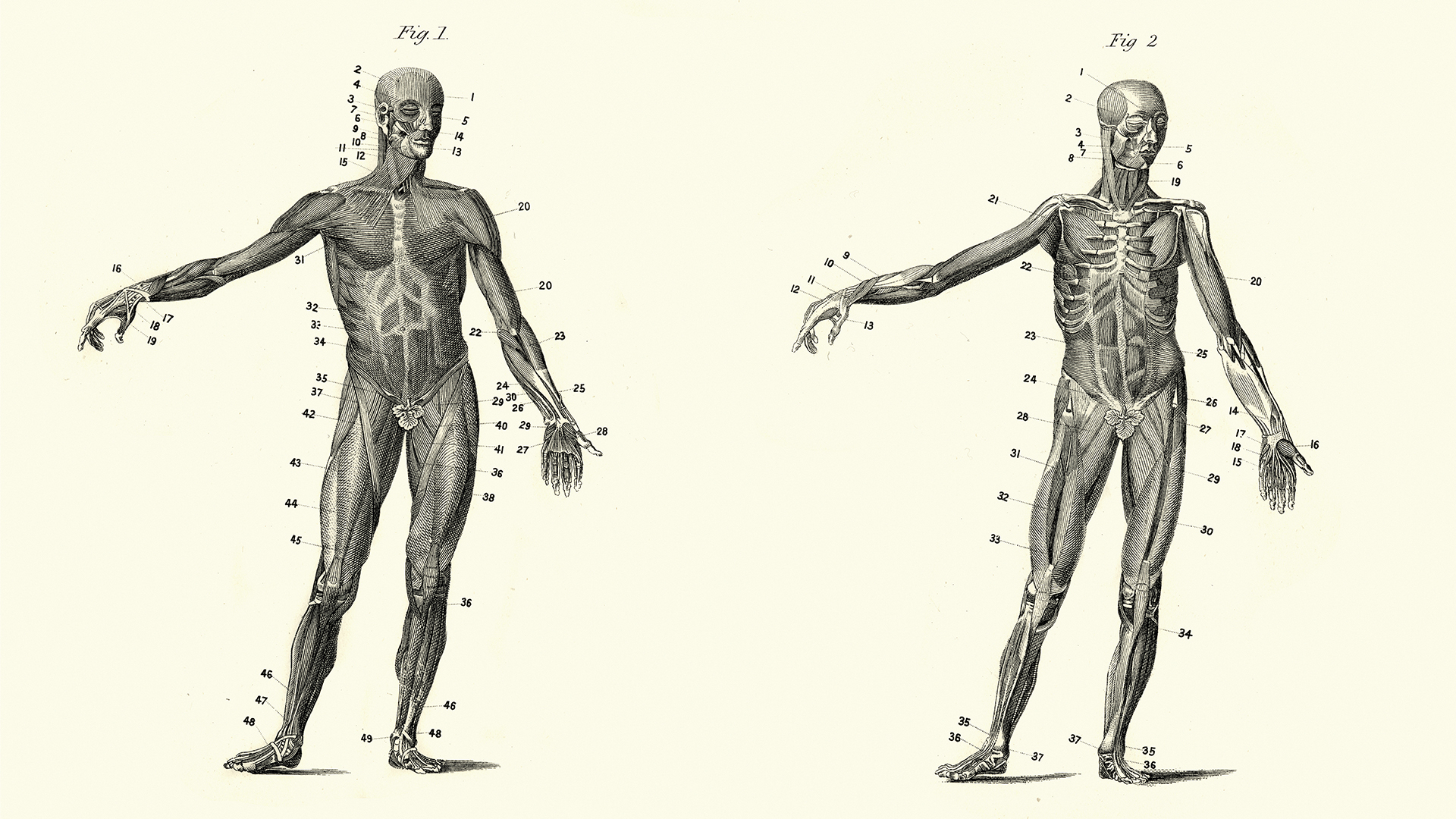

The science of anatomical art

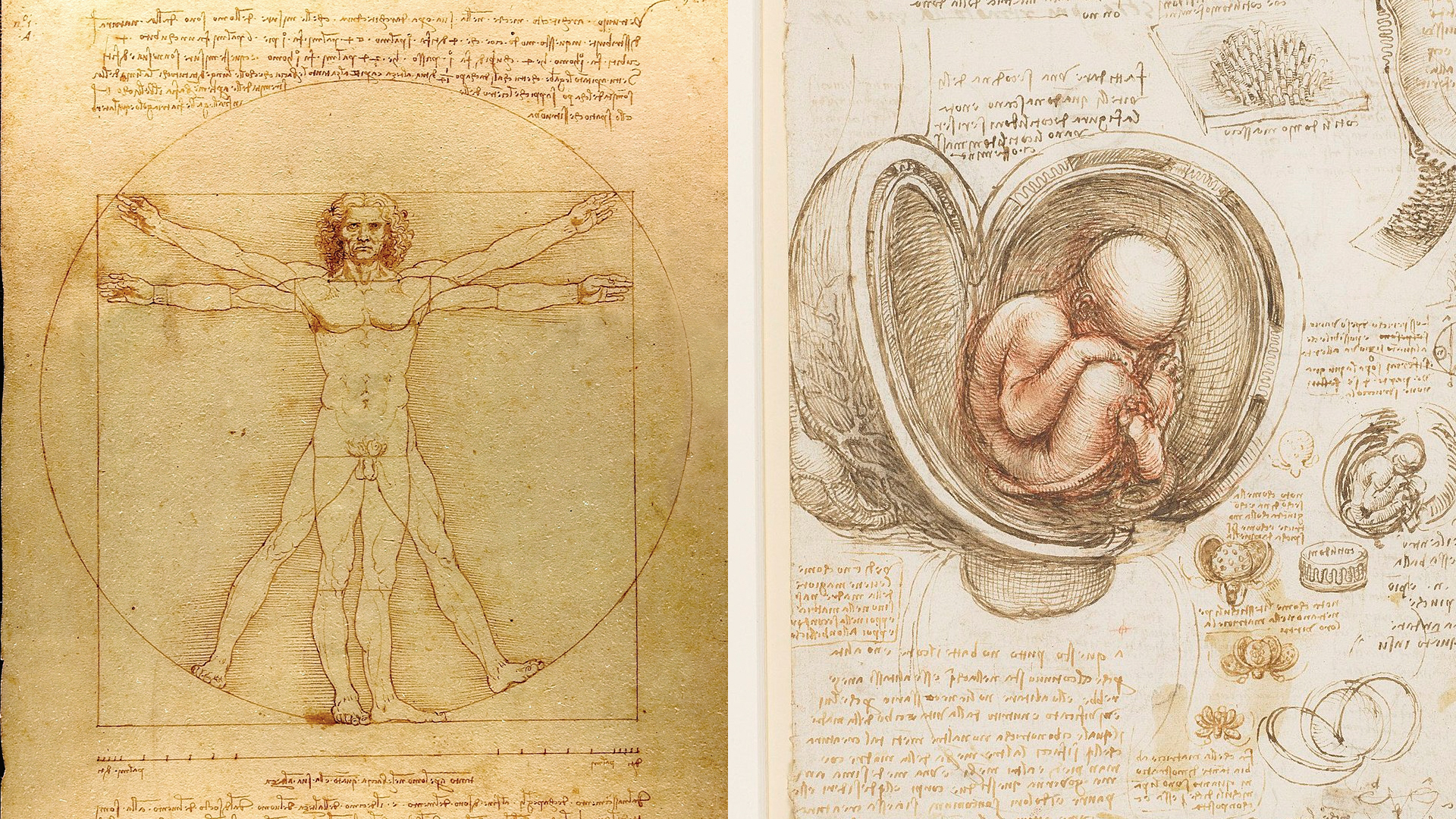

Until now we have focused on sculpture, but all sculptors need to be able to sketch out the germ of their idea before they begin to chisel marble or model a cast for a bronze. A near-contemporary of Michelangelo’s, fellow Florentine Leonardo da Vinci was not just an artist, but the typification of the phrase ‘Renaissance man’.

He was a true polymath: an artist, sculptor, engineer, scientist, mathematician and much more. Relentlessly curious and inventive, da Vinci was fascinated by the human body: by its bones, muscles, sinews and skin, by its fleeting facial expressions, and by the medical science that was just starting to understand more about how it was all put together.

He was also, like many Renaissance men, a classical scholar, and as a mathematician he was fascinated by the ancients’ theories and equations governing proportion and harmony in both the physical structure of the human body and its representation. Michelangelo knew that his David’s head and hands needed to be proportionally bigger than life to attract the attention of the viewer. Da Vinci knew the equations that govern how much, and why.

Da Vinci’s drawing The Vitruvian Man, 1490, examines the relationship of human proportions to geometry. It takes its name from the treaty by the 1st-century-BCE Roman architect, Vitruvius, whose theories inspired its creation by da Vinci. Comic book artists will be familiar with some of those theories: among them is the dictum that the ideally proportioned figure should be the height of eight of its own heads.

Da Vinci’s representation of the Vitruvian Man takes some of Vitruvius’ ideas and improves on them. For example, the polymath has added the extra limbs, capable of depicting a range of 16 different poses. Vitruvius believed that the human body could fit into both a circle and a square.

Leonardo, however, recognised that the square and circle surrounding the figure can’t both have the same centre; instead the square is centred on the groin. This seemingly small and abstract change makes a radical difference – it shifts the idealised body’s centres of gravity so that they’re in line with the way that we actually balance and shift our weight.

Adopt the contrapposto pose again and you’ll notice that much of your pivotal weight is distributed through your pelvis and hips; it’s shifts here as much as in your shoulders, chest and waist that allow your body to move around and change stance and position while your feet are both still on the floor.

Leonardo’s discovery is a quiet revolution in depicting realistic weight and force distribution. Compare his drawing to another Vitruvian Man, this one by Giacomo Andrea, that follows Vitruvius’ ideas to the letter, and the figure looks stilted, weightless and two-dimensional. In fact, it’s strikingly similar to the Bronze Age kouroi.

Something darker than just geometrical skill contributed to Leonardo’s mastery of anatomy, however. His success enabled him to gain permission to do something forbidden to many jobbing artists, something highly controversial in a predominantly Catholic Europe that believed in bodily resurrection on the Day of Judgment. He was allowed to dissect corpses.

Da Vinci proved his skill first in the field of topographical anatomy. This observational drawing simply involves looking at the human body – naked, but still clothed in flesh – and observing the shapes, lines and planes created by the muscles, bones and organs beneath the skin.

Having proven himself a master of this, he was then allowed to dissect the bodies of dead patients at hospitals in Florence, Milan and Rome. He made studies of the skeleton, the vascular system, the muscles and tendons beneath the skin, the brain, and of a foetus in the womb of a pregnant cadaver. His work on anatomy revolutionised not just art but medicine.

Many doctors had begun the study of anatomy, which was in its infancy, but few could draw like da Vinci, and even fewer had sufficient status with Church and state to allow them to explore dissection for science’s sake alone. It was da Vinci who first asserted that the Hippocratic idea of the humours – substances excreted by different organs that affected health and mood – was inaccurate, and da Vinci who first posited that the heart was the centre of the circulatory system.

Meanwhile, in the world of art, his anatomical drawings were copied by luminaries of the Renaissance such as Cellini, Vasari and Dürer. He helped to define how movement worked upon the limbs and joints of the body, making art become ever more lifelike.

Depicting the female figure

From the classical era to the Renaissance, the focus of anatomical art had mainly been on the heroic male form. Despite its prevalence in early figurative art, the female figure was not studied in the same way. In Ancient Greece, even the luscious figure of the love goddess Aphrodite had remained modestly clothed.

The only female models that artists studied or depicted nude were widely assumed – often correctly – to be prostitutes. But one sculptor changed the way that women were represented anatomically, even though his devout subject is depicted with her clothes firmly on.

That sculptor was Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and he’s credited with moving sculpture on from the Renaissance into a new form: the Baroque. One of his greatest sculptures is the religious subject of the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. This ascetic holy woman would periodically go into ‘raptures’ – strange fits that changed her perception and twisted her body (she may have had temporal lobe epilepsy).

Before Bernini, Saint Teresa was often shown as a wimple-clad nun, straight-faced and dour. Bernini depicts a scene from her visions in which she claimed to have been visited by an angel, who stabbed her with a fiery golden spear.

She described the experience as both painful and wonderful, using sensuous language that might have been more appropriate to a newlywed describing her wedding night. Bernini certainly seemed to think so. He sculpted Saint Teresa’s religious ecstasies as a flurry of twisting limbs. The saint gasps, eyes closed. It’s a transgressive, sensual depiction, and nobody except Bernini had ever been brave enough to do it.

This would have been impossible without the centuries of rediscovered art and science and mathematics that had gone before him. The combination of the invention and rediscovery of contrapposto, the knowledge of what to exaggerate and what to make true to life, and the strategies for doing that effectively – as well as the refinements made to classical theories by the polymaths of the Renaissance – all set the stage for a world in which the depiction of the human figure would become one of the ultimate art forms.

This article originally appeared in Paint & Draw: Anatomy. Buy the bookazine from Magazines Direct.