Catwoman should have been a slam dunk.

It was the early 2000s, and still riding high off a decade of Batman success, Warner’s executive suite gave the overdue film its blessing. It had a buzzy new director in Jean-Christophe “Pitof” Comar, known for his unorthodox, hyperreal filming style. And it had Halle Berry, a Hollywood sex symbol who’d already breathed life into another iconic comic book character as X-Men’s Storm. With the disappointment of Joel Schumacher’s Batman films in the rearview — and the promise of a “serious” auteur poised to reboot Batman in the near future — Catwoman was poised to usher in a new era for DC.

“It was meant to be sort of a return to this very genre-y, grounded vengeance story,” screenwriter John Rogers tells Inverse. “And then we did none of that.”

Catwoman began as a spinoff for Michelle Pfeiffer’s iconic feline fatale in Batman Returns and remained tethered to the world of the 1992 film even after Pfeiffer’s departure threw a wrench in those plans. Instead of a standalone adventure for Selina Kyle (who only Pfeiffer was contractually allowed to play), Catwoman became an origin story for an all-new character.

Halle Berry took on the mantle as Patience Phillips, a mousy desk worker who is unceremoniously murdered by her employer after stumbling across a major company secret. When a horde of cats miraculously brings her back to life, Patience becomes Catwoman and vows to get revenge against Laurel Hedare (Sharon Stone), an ex-model turned skin care guru whose latest product is literally making her customers’ faces fall off.

Catwoman was a critical and commercial failure. It made $82 million at the box office on a budget of $100 million and currently has an 8% score on Rotten Tomatoes. In a review, The A.V. Club called it “relentlessly gaudy and in love with its PG-13 approximation of kink.”

But the movie’s director sees it another way: “A female character as the lead hero,” Pitof tells Inverse. “People were not ready for that.”

In the end, the film became a cautionary tale of epic proportions. Production delays, a hastily rewritten script, undercooked special effects, and a general disinterest in nuanced, female-led stories all combined to create one of the biggest flops in superhero movie history. Two decades later, Inverse speaks to five people involved with the infamous film to find out where it all went wrong.

THE BEGINNING

The story of Catwoman begins in 1992. After the release of Batman Returns, producer Denise Di Novi decided to move forward with a spinoff starring Michelle Pfeiffer as Selina Kyle. But Di Novi’s passion project languished in development hell for years before emerging as something dramatically different.

Pitof (director): Catwoman was decided right after Batman Returns. For a reason I don’t really know, the thing dragged and years passed, and then it was completely forgotten.

John Rogers (screenwriter): Dan Waters, who wrote Batman Returns, tried to write the Michelle Pfeiffer Catwoman sequel, and the movie languished for years and took endless drafts. Finally, he quit and said, “Ah, the Catwoman movie, it can’t be made.” Years later I got a call from Denise Di Novi, and she said, “We have been working on this Catwoman movie for 10 years. We have got a draft that nobody really likes, but we’re trying to move it forward. We feel it’s a very viable project. Would you come in and work on it?”

“In town, nobody wanted to be Wonder Woman.”

Pitof: At that time at Warner Bros., two projects were fighting: Wonder Woman and Catwoman. Warner Bros. couldn’t do both. They had to pick one or the other, so they picked Catwoman.

Bill Brzeski (production designer): Wonder Woman doesn’t work because she just always does the right thing. There’s never a question in her mind, kind of like with Superman.

Pitof: In town, nobody wanted to be Wonder Woman. She was tacky. She was not attracting people. Catwoman was more feral, sexy. The girls in Hollywood were really after Catwoman.

THE PLOT

With the writing process beginning in earnest, Catwoman almost immediately ran into legal and plot issues as the team attempted to keep the studio invested in a female-led superhero movie.

Norma Patton-Lowin (Halle Berry’s makeup artist): This film was meant to be the beginning of Catwoman and her transition into being the iconic character that everybody knows.

Pitof: The script went through a lot of evolutions. The one that is on screen has nothing to do with the original.

“The powers that be could not wrap their head around another image of women.”

John Rogers: I actually found the pitch documents in my storage unit the other day. The first line of the pitch document is: “This cannot be a heightened reality, surreal movie, like the Schumacher Batmans. It has to be a grounded crime story.” So my script was much darker and much more violent. It was meant to be sort of a return to this very genre-y, grounded vengeance story. And then we did none of that.

Bill Brzeski: I think a lot of that stuff got lost in translation. The people who made the movie were coming from a different place.

John Rogers: The powers that be could not wrap their head around another image of women.

Pitof: A female character as the lead fighter hero. People were not ready for that.

John Rogers: In the draft before mine, they had insisted on a scene where Catwoman, in the middle of a chase sequence through the city, smashes through the window of a department store. Here’s a mother talking about how a dress fits on her daughter and Catwoman stops and does a speech about body image before she then continues the pursuit as the police thunder up the stairs. There was a lot of, “We have to write speeches justifying why she does this.” I’m like, “Indiana Jones doesn’t do that. James Bond doesn’t do that.”

Bill Brzeski: A lot of the problems with the script were her superpowers and how she got them.

John Rogers: The execs were like, “We can’t make it Selina Kyle because there’s a contract issue. So if it’s not Michelle Pfeiffer, who we can’t afford anymore, it can’t be Selina Kyle.” That’s why it’s Patience Phillips.

Bill Brzeski: They created a backstory for the character that didn’t really exist in DC Comics.

“It winds up being about evil makeup.”

John Rogers: Catwoman became an avatar of wronged women and vengeance. There was originally a whole historical sequence where you see [the Egyptian cat goddess] Bast bring the first Catwoman back to life, and then you see the Catwomen of history and all this other cool stuff. Later, it became a speech by Frances Conroy where she explains the mythology.

Bill Brzeski: There were many conversations about the villain, too. The cosmetics company was a hard sell.

John Rogers: At first, the axis of the story was the domestic labor of housewives. Then, we turned it into a bioweapon thing. Then, I made Patience a vet so it would make sense that she’s working with animals. Later, she winds up being a graphic designer. It winds up being about evil makeup.

Norma Patton-Lowin: It was a skin cream, actually, but she wasn’t just fighting against the makeup. It’s about what it was doing to us as a society.

ENTER: HALLE BERRY

Production got a major boost when Halle Berry officially signed on to play Catwoman, but with an A-list star came added pressure to deliver.

John Rogers: Both the director and Halle signed on to my draft. I was glad my script was the reason she signed on.

Pitof: I was the one really fighting to bring Halle on board. To cast a Black woman as Catwoman was something of a tradition, and I always saw Catwoman more as Halle Berry than Michelle Pfeiffer.

“I wanted something more feral. I wanted to show skin.”

Bill Brzeski: When they brought Halle Berry on, it seemed to amp the production up in the press and at the studio.

Pitof: Everything was built around Halle Berry. She was the center of everything.

Norma Patton-Lowin: I was very conscious of the pressure of coming up with the iconic Catwoman look. I had to show the innocence of her in the beginning when she was just Patience, as well as the transition as she becomes Catwoman.

DESIGNING CATWOMAN

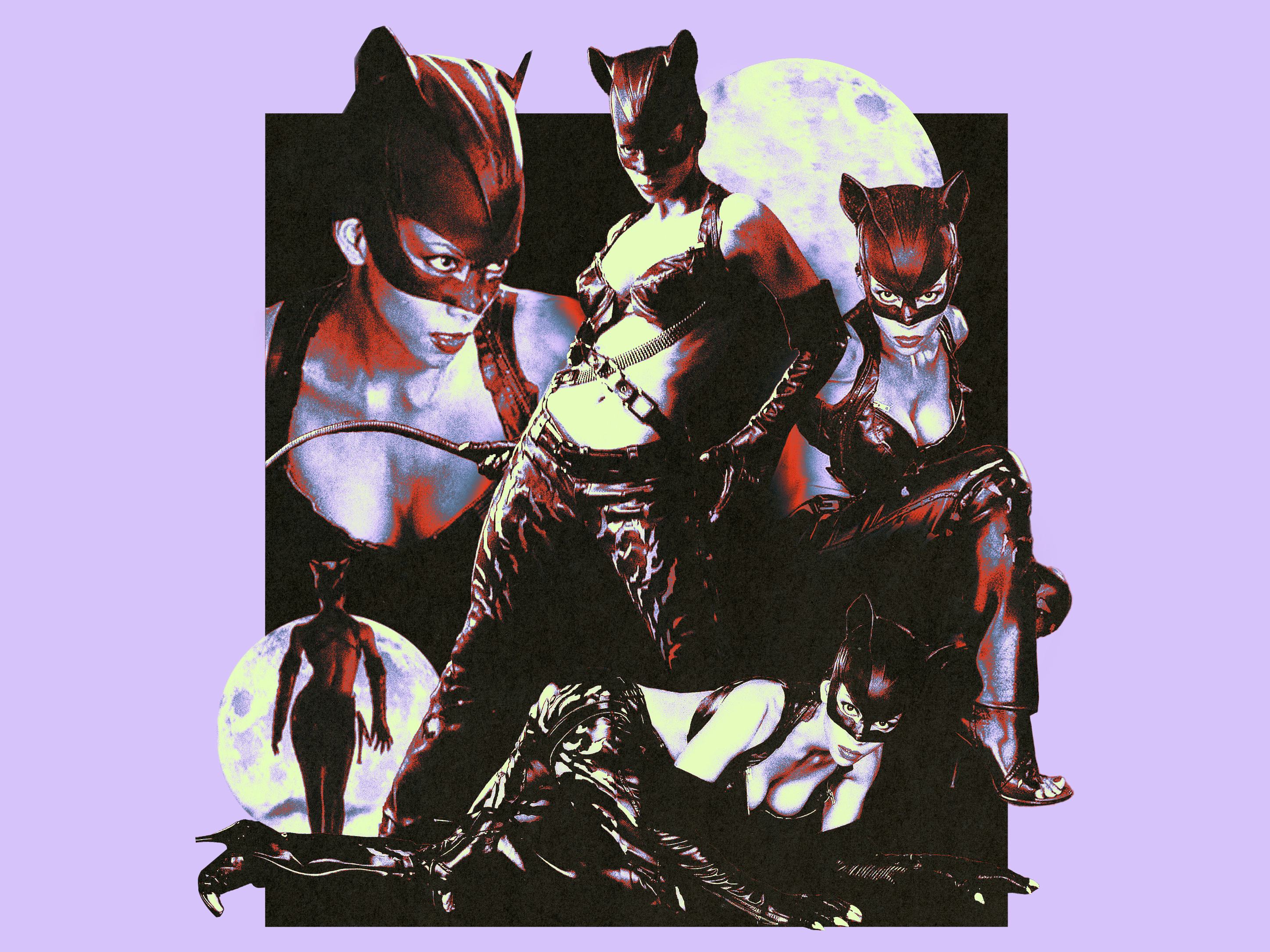

Catwoman’s biggest draw (and biggest controversy) was Halle Berry’s costume. Behind the scenes, there was plenty of debate and disagreement over how it should look — and how it should be revealed to fans.

Pitof: My first research was not that much about comic books but more about how to play with a woman’s body and give her catlike movements. I was watching lots of documentaries about cats. I worked with a dancer to find the right fighting style. One of my inspirations at the time was capoeira. Later I worked with a storyboard artist and an illustrator who came, of course, from the comic book world. It was a mix of everything.

Bill Breski: The problem with the character is she’s got a sexual component that no one quite knows how to handle. That goes all the way back to putting Michelle Pfeiffer in patent leather.

Pitof: The Pfeiffer costume was completely S&M, very plasticky and covered the whole body. I wanted something more feral. I wanted to show skin.

John Rogers: We were talking about when she transformed and became Catwoman, I was like, “What happens is she gets more confident.” But the studio was like, “No. We need a hot, sexy, short skirt.” I said, “Well, that’s not confidence for a woman, that’s sexy to you.”

Pitof: We had a lot of cooks in the kitchen. But I think we pretty rapidly came to an agreement.

Norma Patton-Lowin: For the mask, all we were seeing were her eyes and her lips. I had to go with a bold look for both. I didn’t want her to get lost behind that mask. I made the heavier smoky eye with a slight sparkle to it, because we were shooting a lot at night. I wanted something to show through. I also used bronze body makeup all over because I wanted the light to pick up all the musculature and sinews of her body. She looked like a bronze goddess. She looked just like a statue.

“She kind of looks like a Québécoise stripper.”

Pitof: The film was supposed to be a closed set. The studio wanted to keep the whole movie a secret. “We want to reveal the costume in the movie.” That was the plan. But we were shooting outside with Halle in the suit, so somebody was bound to take a photo of Halle. It’s impossible to prevent that. So at the last minute they said, “OK, so we have to make an announcement and show Halle in the suit,” and they organized a photo shoot with the costume.

Norma Patton-Lowin: Cliff Watts, who’s an amazing photographer who’s worked with Halle over the years and is a very dear friend of hers, he came up and did the photos for it and did a fantastic job.

Pitof: Personally, I hate this photo. I wasn’t part of it. They shot that in LA when I was in prep in Vancouver. Then, they released the photos without saying anything.

John Rogers: I remember they called after they unveiled the outfit and said, “Hey, do you want to do press for the movie?” I said, “I don’t. No, I’m not really super comfortable with the outfit. She kind of looks like a Québécoise stripper.”

Pitof: It was the start of social media and people started to say, “We don’t like the costume.” I think the fans didn’t like the way they’d been approached. Warner Bros. was saying, “Take it or leave it.” I was very disappointed by the way they acted. Warner was like, “No worries. They will calm down. We don’t give a shit.” But you have to give a shit, man!

John Rogers: That’s why you want representation. You want women making these movies so you’re not putting everything through a male gaze of older men that just aren’t fans.

BEHIND-THE-SCENES DRAMA

Just as things were getting started, the studio decided to clear house, creating even more issues as Catwoman prepared to begin shooting.

John Rogers: After about two years of turning in drafts and chasing expectations, then trying to do notes for people who didn’t know what they wanted, I got a draft done that Halle liked and the director liked. And then had a conversation with the execs. “John, we believe we’ve reached the end of our creative journey with you, and we’re going to find some other writers to work with the director.” Which is often quite common. I said, “Oh, that’s great.” I finished the meeting like, “That was a good conversation.” And my manager said, “You just got fired. You’re not going to be able to go back on the lot.” He was right. I was actually blackballed at Warner Bros. for a year. They rewrote my script from the ground up.

Bill Breski: They fired the first production designer, too. I don’t know why. He was French, and there was a whole French contingent making the movie. Maybe the studio thought it was going too much in one direction. In any case, they asked me to do it and I said OK.

“The whip is for Catwoman, not for me.”

John Rogers: I heard they were having problems. I heard they were writing pages on set. I heard they were having problems with the director, who was French, to the point where the Warner Bros. execs were like, “He’s bringing too much of a European sensibility to it.” He is, in fact, French. You probably shouldn’t have hired a Frenchman, in that case.

Pitof: You work for 15 hours a day on set. It’s really, really tiring. And it was Vancouver, so it’s fucking raining all the time. It was depressing. In Hollywood, as a director, you’re not free at all. In a big movie like that, you’re not the director, you’re a CEO. Above you, you have the board of directors. If you do your job, they keep you, and if you fuck it up, you’re fired. That’s very simple.

George Borshukov (visual effects development): The whole crew was joking about Pitof. We knew that it was going to be a mess. We had heard the stories. He was very eccentric.

Pitof: The thing is to try to find light wherever you can and push people, but in a good way. The whip is for Catwoman, not for me.

THE LOOK OF THE MOVIE

Meanwhile, Pitof was busy bringing the world of Catwoman to life. In order to make Catwoman even more catlike, Pitof secured the VFX studio that worked on The Matrix. However, the movie soon ran into issues yet again.

Pitof: The first assignment was to define the worlds and the character. Back then, I was really fascinated by video games. My son was playing Lara Croft. I was completely fascinated by the way the camera worked in the video game: wide angle, following the character.

John Rogers: Pitof was doing stuff with special effects in action. That’s why they hired him.

Bill Brzeski: Part of being Catwoman is, you need to be up high. Cats are on fire escapes. They’re up and walking along the parapet walls of buildings. She’s not a ground creature. We tried to create a place that would cater to that kind of creature. It had a little bit of Rear Window. You could see out the back and see that little courtyard where her bike might be.

Pitof: For The Matrix, Warner Bros. had set up a company called ESC. When I started Catwoman, they were about to shut down the company because they had no use for it. I begged them, “No, no, let’s keep the company open just for Catwoman, and then you can do whatever you want with them.”

George Borshukov: The focus was to replicate Catwoman digitally for those scenes where you see her jumping on roofs and fighting. We also did some facial capture.

Pitof: We did a lot of motion capture with Halle Berry. We spent a whole day doing movements with Halle with a suit with all the dots on it and with the people from ESC.

George Borshukov: Halle had to stay in a still position with all these cameras pointing at her. We took pictures of her with the costume, without a costume, with makeup, without makeup.

Dan Rosen (associate visual effects supervisor): I was tasked with designing “Catvision” a first person view of her super heightened visual awareness. We wanted the effect to allow the audience to immediately experience Catwoman’s hyper-focused sight and see what she was tracking.

Bill Brzeski: The problem with the visual effects was, the only thing they couldn’t quite get yet is Catwoman. They had sold a bill of goods based on all this movement. The character could move like this crazy thing. We call that a digi-double. And it didn’t animate quite right. I always thought they relied very heavily on that. Maybe we should have been a little more analog stunt-y as opposed to trying to be digital stunt-y, but I didn’t know any better either at the time.

George Borshukov: The stills look really good, but the moment it got rendered and incorporated into the actual movie, the scene really got panned. Computer graphics were still being developed. We put a lot of work into this. It was pioneering work and it was recognized as such at the time. We pushed the envelope. But it was still, I won’t say the early days, but it was like the Middle Ages of computer graphics.

Bill Brzeski: As a director, Pitof was a very nice guy, but he was more interested in the visual effects aspect of the story than the story.

THE FINAL FIGHT

Catwoman ends with a huge confrontation between Berry’s Catwoman and Sharon Stone’s aging model Laurel Hedare. Hilariously, the bulk of their battle takes place in a warehouse filled with huge, blown-up images of Stone.

Bill Brzeski: It was your classic fight on the edge of a cliff, basically. They had this big fight scene inside this warehouse that had all these billboards of Sharon Stone’s character. We were just getting computers doing that kind of Photoshop stuff. So all of a sudden you could very inexpensively make gigantic images of a person.

Pitof: I wanted the action to be as tough as possible. But Sharon Stone wanted to do her own stunts, and I said, “Well, come on, I don’t want Sharon Stone to hit Halle by accident.” I was always trying to deal with the stunt double and the star, but never the stars together. It was a lot of shots.

“Apparently, it was very popular in Turkey.”

Dan Rosen: I put a few pre-visualizations together for a pivotal, final fight sequence that Pitof asked for in the 11th hour of the project. I composited a few of those shots myself up until the very last hours left in the schedule.

John Rogers: I read the shooting draft for the arbitration — that’s when you have to go argue over whether your name should stay on the movie. They’re like, “Well, what do you think?” I said, “Look, I know you’re kind of mad at me, but I would like to point out that the giant, final fight scene in your summer tentpole movie is Halle Berry beating the shit out of a 50-year-old woman in a pantsuit. And that’s maybe not as cinematically gripping as you might hope.” And the person on the other end of the phone is like, “But her skin is very hard.” I’m like, “Because of the magic makeup, I got that. But I do not think you can get around the fact that that is the modern-day equivalent of watching Beyoncé beat the shit out of Hillary Clinton for 20 minutes. And I don’t think that’s the ending to a superhero movie.”

THE AFTERMATH

Catwoman premiered in July 2004 and was almost universally panned.

John Rogers: I never saw it in theaters. The night of the premiere, my wife took her sister. I believe she was like, “Well, that was unfortunate, but we did get to meet Benjamin Bratt.”

Norma Patton-Lowin: I think it was a fun movie. It’s been bashed so often by so many people, and it wasn’t given a chance. Had there been a second one, we would’ve then seen the iconic Catwoman that everybody knows and loves.

John Rogers: Apparently, it was very popular in Turkey. Foreign sales were great. It has a fan base. I don’t understand why or how. I think it’s just a sign of how monstrously shitty African American representation was in genre films at the time that even for an insanely bad movie like Catwoman, it was like, “Holy shit, a Black lead!”

Bill Brzeski: They really should have developed the script some more so they could do something with a great actress like that. They had this great piece of IP, but we just couldn’t get there. Then they went, “OK, we can’t make superhero movies with women for a while,” instead of analyzing it, which is really stupid.

John Rogers: I don’t fault Denise Di Novi at all. She was trying to get the movie made after 10 freaking years. It was very apparent that Warner did not like making these movies, did not enjoy going to see these movies, and, in particular, thought you had to write a female action hero in a different way than a male action hero.

Pitof: Hating the movie is fine, but then you feel some people are getting personal and it really feels horrible. OK, give me a break. Don’t shoot the messenger. I’m the fucking messenger. I’m not the message, I’m the messenger.

Bill Brzeski: I’ve done enough superhero movies, and the women’s ones don't tend to work in the same way. Maybe they haven’t figured the formula out yet. I don’t know what our culture thinks a superhero woman should be doing.

John Rogers: Even now, I do not think that women in fantasy, superhero, any sort of genre like that are fully embraced to the extent they should be, considering their impact and attraction to the audience. And back then? No, not at all.

Pitof: Catwoman was ahead of its time, and people were not ready for that. “Oh, to watch a chick kicking the butt of men. No, I don’t want to see that.”

Norma Patton-Lowin: I think people were ready. They were ready for her. If it had been another actress of color, maybe not, but everybody loves Halle, so I think they were ready for it.

John Rogers: This is one of the lessons I use for young writers to learn the difference between a challenge and a warning. I could have heard Dan Waters, the guy who created the role and wrote one of the most successful superhero movies of that time, say, “This movie can’t be done,” and gone, “Well, Dan knows what he’s talking about. I’m not going to touch this.” But instead, with all the hubris of a young man, I went, “Well, he can’t do it. But that sounds like a challenge to me!”