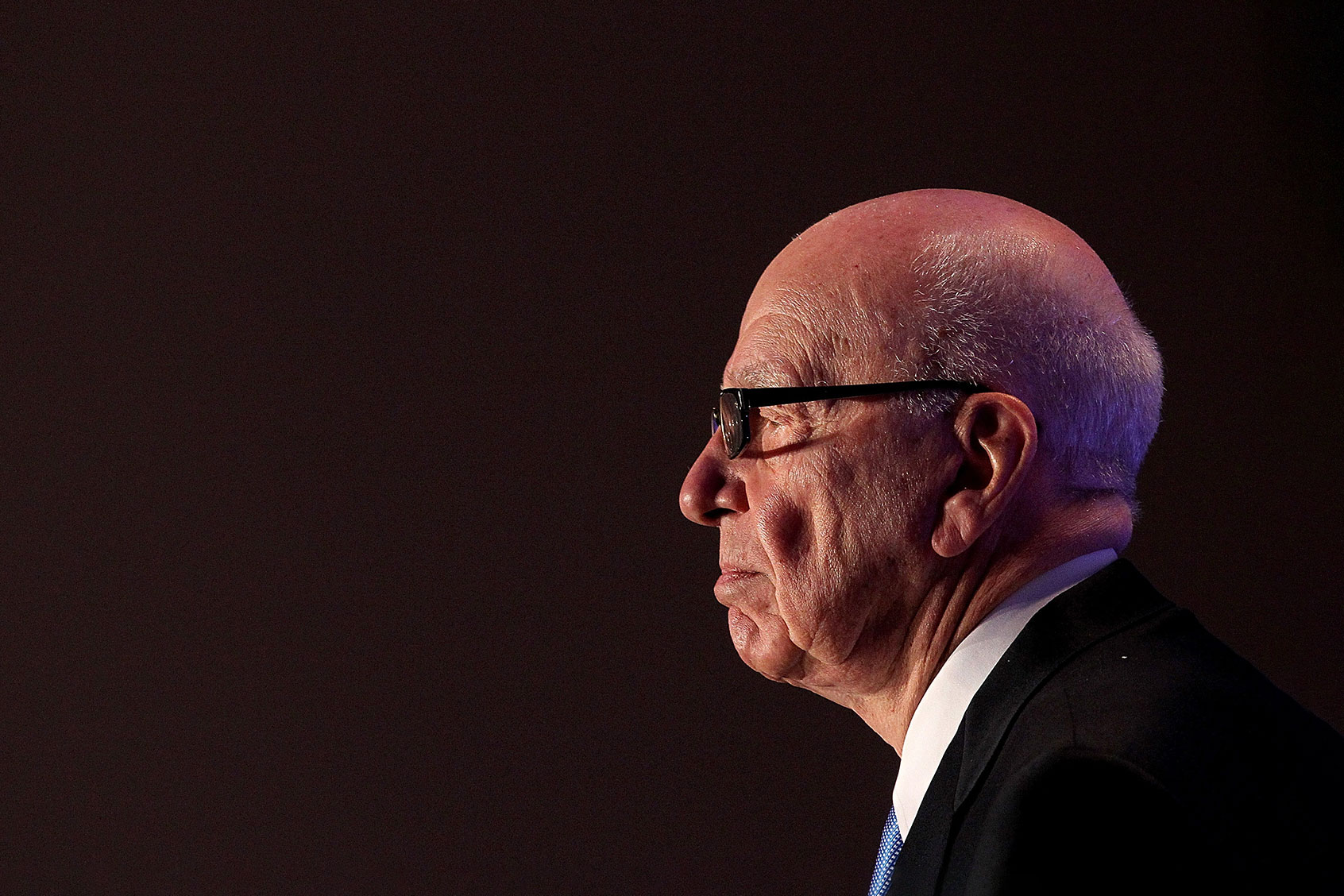

If you think Rupert Murdoch has only been pushing mainstream journalism rightward and for the worse since 9/11, Maury Povich will avuncularly disabuse you of that notion in "The Murdochs: Empire of Influence."

The one-time host of "A Current Affair" gleefully recalls flying to Germany to cover the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, to the bemusement of Dan Rather and Tom Brokaw – that era's giants of TV journalism. "A Current Affair" was syndicated TV tabloid trash; what was it doing covering a world event? To answer that, Povich's colleague Gordon Elliott ran to a local firehouse, procured a pickaxe and took a few theatrical digs at the great concrete symbol of communism.

Then a local asked Elliott, "Oh, can I have that for a while?" The tabloid newsman hands the guy the axe, and he starts swinging. One enterprising photographer's click later and boom – there he was on the cover of Newsweek.

Compared to what Murdoch would wreak on the media landscape, political discourse and democracy on the whole, this is a cheeky detail. But it makes Povich's point: If something is lacking in the landscape – whether that refers to a frame of history or the full scope of it – he will not only fill that gap but use that device to alter the full picture.

Not only that, Povich adds, there's no unplugging or overwriting what Murdoch's done. "You can't erase it," he says at the top of the second episode. "It's here to stay."

Out of the tens of journalists, biographers and political consultants serving as on-camera experts in CNN's seven-part series along with whatever species Roger Stone is classified as these days, Povich stands out as the guy who gets the joke. Why wouldn't he? Murdoch made Povich a famous man by bankrolling one of the trashiest shows on TV.

Even that was a stepping stone to bigger things. First, it was "A Current Affair," then a broadcast network, Fox, then Fox News and . . . well. We're living in the world Murdoch has wrought – something most of us would rather forget.

If something is lacking in the landscape, Murdoch will not only fill that gap but use that device to alter the full picture.

The producers know that, which is why they take a page from its subject in their shaping of it. Rupert Murdoch, like his henchman, the late Roger Ailes, made a fortune off of giving the audience what it wants. So although "The Murdochs" is based on the behemoth of a feature by New York Times journalists Jonathan Mahler and Jim Rutenberg, who serve as consulting producers and appear throughout, it looks, feels and struts along in the manner of "Succession."

Jesse Armstrong doesn't exactly make a secret of having patterned the Roys after the Murdochs, along with the Hearsts, the Mercers, the Redstones and others. But it takes seeing a biographical, extensively sourced look at the baron's family to appreciate the accuracy of his portraiture.

The only detail Armstrong really fudges is the Roy children's intelligence, but that's on purpose. If Shiv, Kendall and Roman were as capable as Lachlan, James and Elisabeth, "Succession" wouldn't be half as entertaining. It's better for all of us that the Roy kids are mulling their place in a legacy that mirrors that of the Murdoch children, only with the brainpower of the Trumps.

"The Murdochs" is two stories presented in tandem, as Mahler explains. The first covers the rise and dominance of Rupert Murdoch, media mogul. The second is the story of Murdoch as a father.

It opens with the near-death incident in 2018 that kicks the question of who will inherit the kingdom into overdrive, before stepping back to examine Rupert's misshapen youth as the privileged son of a distant father he could never please. When Rupert realizes his parents' modest media kingdom will not pass to him, he makes it his life's mission to overshadow the modest legacy dad built.

Murdoch's steady empire expansion is common knowledge to those who care to know about such things. But "The Murdochs" excels at filling in the story's emotional and psychological blanks, which is where the juice is. For a family that willingly gives away very little about themselves to the public, there's a lot to be read in the moves Lachlan, James and Elisabeth make – and their father's regular efforts to play them off of one another as a sort of Darwinist test of fitness.

But the relationship between Rupert and his children is even stranger than that of their fictional counterparts because, by all accounts, he does seem to care about them. It's just that he cares about his empire even more.

Such grace notes of universal acknowledgment allow the viewer to find some way of respecting the tenacity fueling Murdoch's monstrous nature.

"The Murdochs" is even-handed in its examination, to the point that it enables a person to absorb insights from truly odious people with equanimity. Stone, for instance, has nothing but respect and admiration for Murdoch, of course. But that's presented within a mix of folks who concede the bold ruthless of Murdoch's business acumen even if they disagree with despise how he plays the game. That is to say, knowing what we know about Stone, if he admires the man, the show helps us to get it.

Such grace notes of universal acknowledgment allow the viewer to find some way of respecting the tenacity fueling Murdoch's monstrous nature. The story of an early kidnapping gone awry that led to a woman's death opens our eyes to the family's vulnerability before their paterfamilias built the fortress around them; they are human, after all.

And yet, the head of this family also pushed thousands of journalists out of their jobs in one fell swoop to appease a prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, who was not friendly to unions or labor organizing. This is merely one of the many obscenities Murdoch is blamed for orchestrating. The later episodes cover the one we know best and are still struggling to shake off – which is Donald Trump's kingmaking.

"The Murdochs" stands on its own merits owing to its double-fisted servings of media insight on one hand and juicy biographical examination on the other. It is nimble and surefooted, illuminating, and above all, entertaining.

Nobody in the family agreed to participate in the making of the series, but the producers make an extensive effort to help us understand who Rupert Murdoch is and what spurs him onward.

By extension, we also come to understand why entities like Fox News and Murdoch's newspapers are so devoted to catering to the darkest side of the human impulse – stirring up our fears and our hatreds, and steering governments into division and ruin. It's all in service of his empire's bottom line and the interests of his constituency, which consists of . . . him.

Most documentary filmmakers are quick to point out that whatever parallels the audience finds in their work and current events are coincidental. In most cases that's true. Ken Burns' recent effort, "The U.S. and the Holocaust" points directly at the similarities between the nativist atmosphere in America and Germany before World War II and the anxieties that have gripped us since Jan. 6, 2021. Even so, he says, he and his co-producers began working on that project in 2015.

Debuting "The Murdochs" six weeks out from the midterms, though, is a choice. It won't impact the outcome of any races – nothing like that. But if CNN wants to make a vaguely admiring, audience-pleasing point about its rival as it lurches rightward to score some of its audience, this is a savvy way to do it.

"The Murdochs: Empire of Influence" launches with a special two-episode premiere at 9 p.m. and 10 p.m. Sunday, Sept. 25 on CNN. Subsequent episode air at 10 p.m. Sundays on CNN.