Science presenter and journalist Dr Michael Mosley was well known not only for his expertise, energy and passion as a broadcaster but also for trialling experiments on himself. From swallowing tapeworm eggs to having areas of his brain switched off, Mosley joined other medical pioneers who weren’t afraid to make use of their own bodies in the quest to learn more about them.

The “father of medicine,” Hippocrates — as well as other important figures from Chinese, Indian, Egyptian, and Arabic history — noted excessive thirst, urination, and weight loss in some patients. These symptoms are related to the condition diabetes mellitus, the metabolic disorder of raised blood sugar. The term ‘diabetes’ refers to the increased passage of urine, and the Latin word ‘mellitus’ means sweet, like honey.

One of the ways Hippocrates investigated his patients was to taste urine for sweetness. And he wasn’t the only historical medical figure to go Bear Grylls on the pee-quaffing. The ancient Indian physician Shushruta (circa 500BCE) described the sweet taste of diabetic urine as ‘madhumeha’ or honey urine. In the 17th century, although British physician Thomas Willis called diabetes the “pissing evil,” he did seem rather fond of the taste of diabetic pee, which he described as “exceedingly sweet” and “wonderfully sweet, like sugar or honey.” I want to know who really did all the tasting.

Did Hippocrates take a swig himself or did he offer it to the patient to try instead? If doctors did taste a urine sample then perhaps this is one of the earliest examples of dedication to the cause. Very noble but, as a medical doctor, I’m glad it’s not part of the Hippocratic oath today.

Agony and ecstasy

Self-experimentation may be controversial, but it has contributed significantly to modern-day medicine.

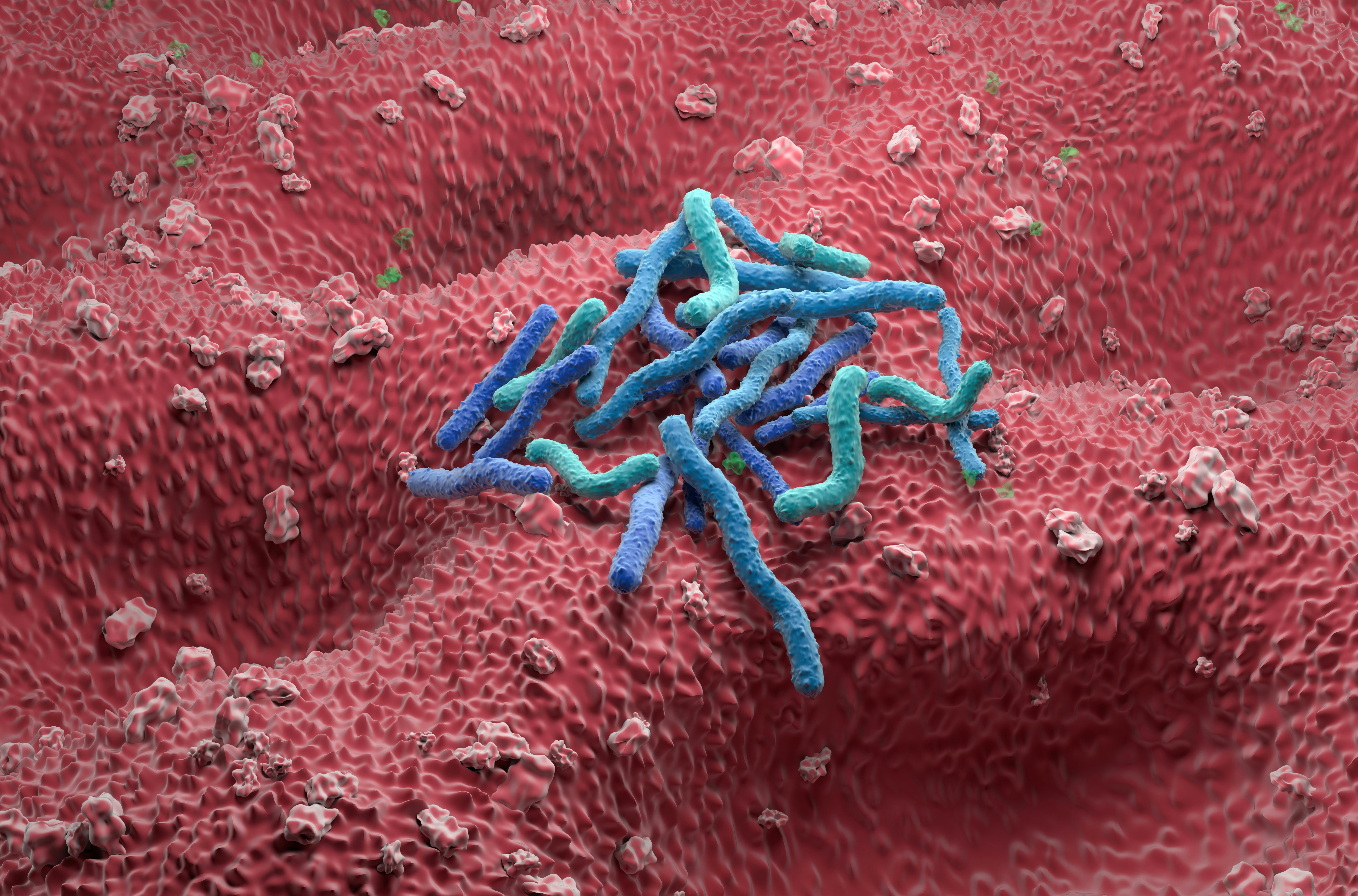

In the 1980s, the physician Barry Marshall noted the association between inflammation of the stomach (gastritis) and the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. Marshall’s research was initially rubbished and turned down for publication in clinical journals — so he took matters into his own hands.

By consuming a solution containing H. pylori, Marshall was able to demonstrate that the bacteria had triggered extensive inflammation. He also cemented the link between H. pylori and the development of stomach ulcers. Finally published soon afterward, Marshall and his collaborator Robin Warren were awarded the Nobel prize in 2005. Thanks to Marshall’s self-testing, H. pylori can be easily treated with antibiotics and other medications.

Other physicians have deliberately infected themselves with viruses and bacteria to study their spread or effects, including cholera, campylobacter, and yellow fever.

In addition to discovering the causes and diagnoses of conditions, self-experimentation has led to the development and availability of many essential treatments. Take the widely used local anesthetic lidocaine, which prevents patients from feeling pain during surgical procedures without the side effects of general anesthesia. It was developed in the 1940s by Swedish chemists Nils Löfgren and Bengt Lundqvist — Lundqvist tested the compound on himself.

Other experiments have involved synthesizing and testing new drugs, trialing vaccines, and developing key surgical treatments and operations. Many scientists have examined the effects of new compounds as medicines through self-medication and chronicled the effects, including the chemist Alexander Shulgin. Shulgin — known as “the godfather of ecstasy” — self-tested the drug before introducing it to psychologists to use in talking therapies.

Some others have not been so successful. French researcher Daniel Zagury injected himself and several other volunteers with a potential AIDS vaccine, which, although hailed as “daring” and “exciting” at the time, failed to work. Other self-experimenting researchers came across important new discoveries by accident. While developing a new antimicrobial medication, a Danish group tested it on themselves and found that it had unpleasant effects when consumed with alcohol. This led to the development of disulfiram, a medication still used to treat alcohol dependence.

Perhaps the Victorian physiologist Joseph Barcroft is one of the most prolific self-experimenters. His repertoire ranges from the investigation of the effects of cyanide gas to the oxygenation of blood in extreme environments and the body’s response to hypothermia — all tested on himself.

Dr Michael Mosley: human guinea pig

Michael Mosley, then, followed a well-trodden, if ethically questionable, path in using his body as a testing ground for medical research. He really was dedicated to taking one for the team.

In 2014, Mosley infected himself with tapeworm larvae to understand their effect on the human body.

Imagine feeding a second mouth in your stomach that would absorb the calories you’re taking in. Tapeworms have been marketed as a weight loss product for over a century. Since Mosley gained two pounds in weight during the experiment, this suggests that perhaps tapeworms are ineffective weight loss aids as well as highly dangerous.

Mosley advocated for intermittent fasting and the 5:2 diet after following the regime himself. While the diet has since attracted controversy, research suggests that intermittent fasting could not only support weight loss but also reverse type 2 diabetes in some patients.

Mosley was part of a rich medical tradition of self-experiments, joining those whose dedication and fearlessness were enough to test the scientific method in the most personal way possible.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Dan Baumgardt at University of Bristol. Read the original article here.