Since Abdullah Ibhais used to video-call his family three times a day any time he was away, his two young children - aged four and six - cannot now understand why they don’t see him. “Their mother tells them he is travelling, but they don’t buy it,” Ibhais’ brother Ziad says. “They’re questioning every day, ‘why does dad stop loving us? Why did he desert us?’ They think they have done something wrong.”

The children understandably haven’t been told their father is in prison, even though - according to human rights groups – Ibhais has done nothing wrong either. The Jordanian national of Palestinian descent advised the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy that they should acknowledge their role in a failure to pay striking workers at the Al Shahaniya labour camp in August 2019.

Ibhais was later imprisoned after what Human Rights Watch and FairSquare have characterised “an unfair trial”. Ibhais’ cell is just a short drive from Al Bayt, the stage for the World Cup’s opening game. As final preparations were being made at the start of November for Qatar vs Ecuador, Ibhais has alleged he was “physically assaulted by the prison guards”, before being subjected to “complete darkness in solitary confinement… with temperatures near freezing as the prison’s central air-conditioning was used as a torture device” so that he couldn’t sleep for 96 hours. The Independent has not been able to verify these claims.

Ziad says his brother is “on the verge of breaking point”, suffering “the most horrible experience of his life”. The family adds that “the stark difference between the two scenes” will “always haunt” them.

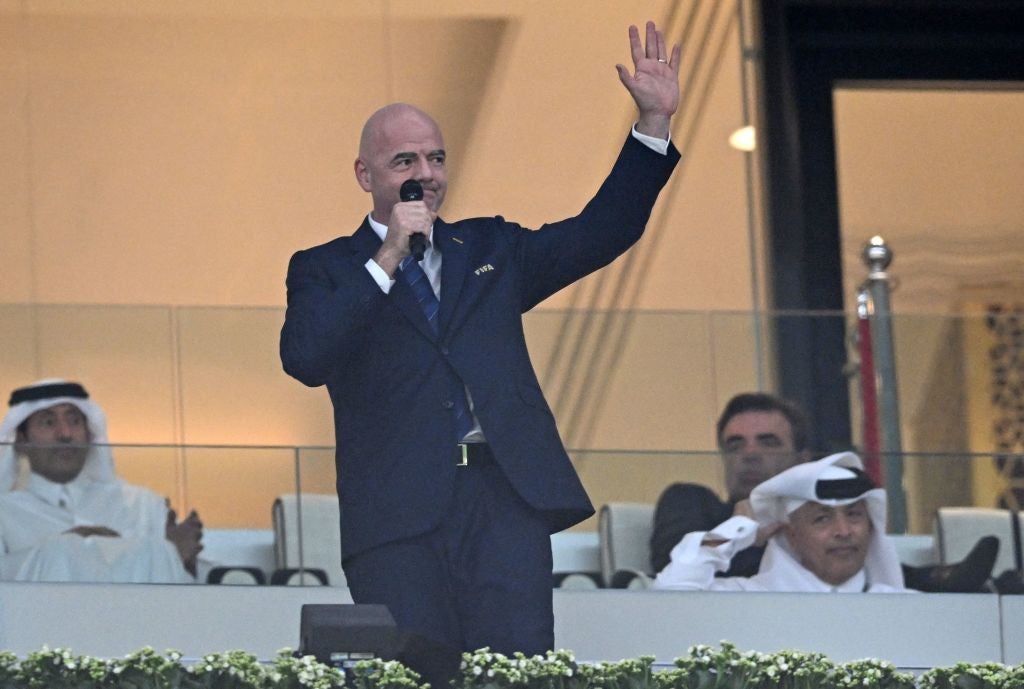

Ibhais’ family accuse Fifa and president Gianni Infantino of being “complicit” in a “human rights travesty”, with FairSquare adding that that “the important thing to remember is that the case directly implicates the World Cup organisers, the Supreme Committee”.

The claims do not just put a different complexion on the competition’s grand conclusion as it reaches the final, the story of Lionel Messi’s career perhaps coming to the most glorious end. Ibhais’ case takes in: migrant worker rights and abuses; unpaid wages; the nature of World Cup stadium construction; how Qatar works; how Qatar spins; how Qatar deals with dissent; the “police state” nature of Qatar; its artificiality; paranoia over the gulf blockade; its lack of civil liberties and all while offering an insight into how the power structure is run.

If that’s a lot, it is worth just laying out the details of his case.

On 4 August 2019, around 5,000 workers at Al Shahaniya labour camp went on strike, having not received salaries for months. Evidence first revealed by Norwegian magazine Josimar suggests that there was concern within the Supreme Committee that this involved workers at World Cup stadiums. Ibhais says he went to investigate, saw that was the case, and advised the Supreme Committee to acknowledge their role and fix the problem.

Apparently the body weren’t so willing to heed this.

According to Josimar, Ibhais was throughout this period engaged in Whatsapp communication with World Cup chief Hassan Al Thawadi, who you will have since seen criticising the BBC for its coverage, describing the OneLove armband as a “divisive message” and also admitting there have been “between 400 and 500” migrant worker deaths.

“So much goes back to that Whatsapp discussion,” says Nick McGeehan of Fair Square. “Abdullah provided it. It says a lot about how it’s been run and why it’s been run.”

In the exchanges, initially published by Josimar, Al Thawadi says the following in a voicemail: “If what’s outstanding is a month’s payment, comms and workers welfare, sit down, come up with a narrative to clarify and explain on how we address this situation, to clarify and explain we have taken steps beyond any other institution, any other organisations to ensure speedy payments for workers. That needs to be clarified, figure it out, if it’s a delay of a month, then put a narrative on it, put a spin on it, if we have to sit down and use the word.”

Khalid Al Naama, the Supreme Committee’s director of digital media, later added: “I believe regardless of whether or not SC workers participated, the fact remains that we have workers that have not received June and July salaries. Any spin we try to put on the delay will risk the State reputation because it would be an admission from us that there is indeed an issue with payments – in fact so bad that we have to pay the workers directly and in cash – because the wage protection system and electronic records failed them.

“It makes us look really bad that all these reforms we’ve been talking about ‘accelerating as a result of the World Cup’ still cannot fix issues. Only response I see making things better is saying it’s been resolved. Nothing else we say will do anything except cause more damage.”

Ibhais continued to argue against trying to “spin” the story or deny. It had been put to him by Fatima Al Nuaimi, executive director of communications, that “a strong PR team know how to cover those mistakes… this is what Saudi and Dubai do”. Ibhais responded: “No. Khashoggi. Yemen. Princess Haya. Libya. When facts on the ground can’t be denied. We need to fix it then do the PR part. Lying is not Qatar’s way and should not be.”

He later said: “Hassan talks and talks and talks and now I am not even convinced we are on the good side. I am convinced now that we are part of the problem, we are trying to clear our name and fix the reputation issues without seeing real change on the ground and this is the worst thing that can happen. Are we really part of a plot to cover up for workers’ exploitation!?”

It was around this period that Ibhais’ brother Ziad realised something was not right.

“He started to tell me he’s having trouble at work and having panic attacks, late in September 2019. I never knew what the problems were until he was taken into custody on 12 November 2019. It was out of nowhere.”

Three days before that, a file had been submitted to authorities by the Supreme Committee containing serious allegations against Ibhais. It had been suggested he was consorting with figures from Saudi media and was out to damage the state. This was a period, McGeehan points out, when there was “intense paranoia about Saudi and Emirati efforts to strip Qatar of the World Cup”.

Ibhais was taken from the offices of the Supreme Committee by five officers and into custody, where he says he was threatened with state security detention, which would have meant six months without a lawyer. He has claimed he was told that if he asked for a lawyer, they would break his legs.

“I was horrified by the possibility of a state security prosecution,” Ibhais told Josimar in the time before his imprisonment. “I thought I was in real danger of a charge that could lead to life imprisonment and the death penalty.”

Ibhais’ brother says he signed a “ready-made” confession under duress. It was not a confession on a state security violation or taking a bribe in action but intention to take a bribe.

“Even the confession is used to establish an intention,” his brother says. “It’s not used to establish a committed crime.”Ibhais later retracted this confession.

The case subsequently took a very long time to go to court, a period in which Abdullah and the family - according to Ziad - “were denied information about the case until 13 months later” and it was transferred from state security police to criminal investigation.

It was finally in April 2021 - by which point Ibhais had been let go from his job due to the state reason of Covid cutbacks - that he was convicted of “bribery”, “violation of the integrity of tenders and profits” and “intentional damage to public funds”. This, according to FairSquare, was based entirely on his confession.

“No other evidence was supplied.”

Ziad outlines the family’s experience of the legal system in Qatar.

“To our experience, the courts were just a legal façade for a political decision. It is clear that there was a decision to silence Abdullah, and that courts had to put a legal cover to that. It is not a legal system at all.

“In Qatari courts, they have some very bizarre rules they work with. The defendant cannot speak in court in any possible way. He is dealt with as if he is guilty from the beginning, so he doesn’t get to talk to the judge. If he talks to the judge, the judge ignores him as if he doesn’t exist. This is how it works.

“The second thing, the lawyer doesn’t ask the questions to the witness directly. The lawyer presents the questions to the court, the court decides which questions they will ask and in what form. It’s not like a normal court where it’s between the lawyer and the witness and if anything goes wrong the judge interferes. It doesn’t work that way in Qatar. The third thing, it’s up to the judge if he will open the floor for the defence or he won’t. That’s what happened with us in the preliminary court. Our attorney asked for 10 witnesses to be questioned and asked that the claimed evidence must be authenticated in court. The judge refused to force the Supreme Committee to present the evidence and he listened only to four witnesses then set a hearing for verdict, without opening the floor for defence. He ruled against Abdullah on the 29 April and he didn’t have to reply to our lawyer before that. He replied and denied the lawyer the chance for defence on the 23 June after the case was closed.”

With Ibhais in limbo over whether the sentence would be executed, he finally contacted human rights groups in September 2021.

“What was remarkable was how much evidence he supplied to support his claims,” McGeehan says. FairSquare and Human Rights Watch initially only focused on the fair trial allegations, which then saw Ibhais go public in Josimar on 25 October.

He had by this stage submitted a complaint through Fifa’s whistleblowing platform and there was for a time some contact with the global governing body’s human rights team.

“At some point, they just disappeared,” McGeehan says. “They ghosted him, for want of a better word.”

Ibhais remained out and with his family until 15 November, when he called German journalist Benjamin Best to say he was being taken into custody. Qatari authorities had arrived and were executing the sentence handed down in April. Ibhais went on hunger strike immediately.

There was then an appeal court judgement in December.

“Even there, Abdullah was put in custody just before the final hearing, so that communication with his lawyer to prepare his defence was hindered,” Ziad says. “Abdullah could not contact his lawyer, even in prison. He was on hunger strike at that time. They didn’t allow any contact.”

Ibhais then spent almost a year in prison before his case went to Qatar’s final court, the Court of Cassation on 7 November 2022.

Ibhais had by then been in solitary confinement for four days.

“The real cause however is the broadcast of the documentary ‘Qatar: A State of Fear?’ on ITV1 in the UK, where Abdullah’s case was one of the main cases presented,” his family said of solitary confinement in a statement. “The Qatari embassy in London sent its response to ITV1’s request for comment on the 30th of October. Abdullah was in solitary confinement two days later, one day ahead of the broadcast.”

The Court of Cassation upheld Ibhais’ conviction, which his family didn’t find out about until weeks later. It means the legal channels for him to be freed are closed, and he will remain in jail for three years - unless given some sort of pardon.“He was very upset when he heard about the Court of Cassation judgement,” McGeehan says. “He has had swings in terms of his mental state, and was on medication. He’s in a difficult place mentally, although he appears to have periods where he is more optimistic.”

This is put in the simplest terms by McGeehan.

“It’s straightforward. This is clearly an unfair trial. He was interrogated without a lawyer. He signed a confession, which was retracted, under duress. If someone makes an allegation like that in court, it’s the duty of a court to investigate if it was given freely and fairly. If it wasn’t, they have to provide other evidence to support the charges. It wasn’t. Three separate courts haven’t done that. We have the full texts of those judgements sitting there.”

Ziad goes even further.

“This is very simple. If a retracted confession is not supported by physical evidence, how can you still bow to it? What’s it based on? This is basically the case. It’s squarely dependent on his coerced confession. There’s nothing except that, no evidence.”

Qatar has denied the claims and insisted Ibhais was convicted on the basis of “an abundance of strong and credible evidence”.

This evidence has never been made known, however, either in court or in public.

So what next? What is possible?

His family and the human rights groups have specifically decided to speak this week, given the build-up to the World Cup, because it can put maximum pressure on Fifa. The governing body has so far only repeated the line that “any person deserves a trial that is fair and where due process is observed and respected”.

“That’s an utterly meaningless statement that gets their Qatari partners completely off the hook,” McGeehan says. “That is communication that again looks in lock-step with the Supreme Committee.

“Why won’t they specifically call for a fair trial in this case? Why can’t they do that? This case was instigated by their partners. The Supreme Committee put Abdullah in harm’s way when they handed that file of unsubstantiated, unproven allegations. Fifa don’t have to say anything about what they think of the merits of the case, but it’s absolutely incumbent on them to specifically demand this man gets a fair trial. If Fifa demands a fair trial for this, then we can start to put questions on the Qatari authorities, but as long as Fifa don’t do that they are implicated in this denial of justice and very heavily so.”

An official statement is even stronger.

“We, the family of Abdullah Ibhais, are calling out Fifa and its president, Gianni Infantino, who once said the World Cup is the voice of the marginalised. Your deeds haven’t lived up to your words. Fifa is complicit in Abdullah’s imprisonment and Fifa’s silence is tearing apart our family. We refuse Fifa’s callous indifference. We refuse to back down: we’re calling today on Fifa to take responsibility and finally own up to this human rights travesty.”

Ibhais’ family are taking an urgent appeal and a complaint to the United Nations working group on arbitrary detention. This is a committee of independent human rights experts, whose job it is to look at the legality of such cases. They can request information from states involved, a power non-governmental organisations don’t have. Not all states respond to that but, if they don’t, the key is the state can’t behind claims they weren’t consulted. That gives particular weight. The working group can then issue an opinion saying that in their view the detention is arbitrary and illegal. The urgent appeal means the working group contact the state directly because they are concerned about the well-being of the individual detained. The family felt that was appropriate given recent developments.

“We’re very hopeful that the working group will find this as an arbitrary detention,” McGeehan says. “If that is the finding, for a case that embroils Fifa, that isn’t going away.

“We cannot force the Qataris to let this man out but Fifa can exert significant influence on this. Fifa’s sponsors can exert significant influence, and they have been asked to do so. They have said nothing publicly, which is a failing on their part.

“We will continue talking about this until Abdullah is out. I think it would also put pressure on the next World Cup hosts. Do the US really want to have this millstone around their next as they prepare to host this next tournament?”

Qatar have 60 days to respond, but the case load can mean it could be a wait of several months to hear from the working group.

There is some other hope for Ibhais - which is that this World Cup finally ends.

“I think it’s possible the Qataris will reach an assessment that his continued imprisonment serves little purpose for them, that he has said everything he has to say, that the pressure is off them, that keeping him in prison will simply keep a spotlight we don’t need,” McGeehan says. “But we don’t know how personal this case is. We don’t know the precise motivations for putting him in jail.”

“We have one possible way, which is to put the Qataris under as much pressure as possible,” Ziad says. “Our best chance is to make them realise that Abdullah is a burden, to put him on a plane and deport him. A pardon would be a surprise if it happens after all what we have seen in court, and all what Abdullah has gone through in prison during the last year.”

Ziad Ibhais can meanwhile barely bring himself to watch this World Cup.

“I didn’t watch most of it - usually I do. I didn’t watch the opening. My kids are following most of it at home. Of course there’s the joy of football, but I can’t forget this was built on people’s misery, on people’s blood actually. My brother is in prison because of this. I can’t talk to him, I can’t see him, his kids can’t see him, his wife can’t see him. I can’t get this personal feeling out when I watch the World Cup, so I try to avoid it.”

The Independent has contacted Fifa, the Qatari state and the Supreme Committee for comment.