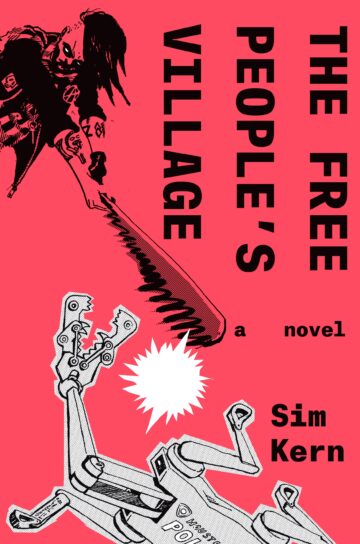

Somewhere in a Texan’s alternative universe, Al Gore won the 2000 election and we’re 20 years into a War on Climate Change rather than the War on Terror. But then as now, Texas ain’t utopia and certain neighborhoods and people tend to get left out of the green revolution. Welcome to the “ripped from the headlines climate fiction story based on real-life activism” by Houston author Sim Kern.

Kern’s The Free People’s Village (Sept. 12, Levine Querido and distributed by Chronicle Books, LLC) draws from Kern’s own experience as a teacher in Houston public schools, their activism with Occupy Houston, as well as the present-day Stop I-45 movement. But The Free People’s Village takes place in an alternate 2020 timeline, where a supermajority of Democrats have passed sweeping climate regulation, transforming the country into a “solarpunk utopia”—but only for wealthy, white neighborhoods.

Protagonist Maddie Ryan, a white English teacher in a majority-black school, spends her nights and weekends as the rhythm guitarist of Bunny Bloodlust, a queer punk band living in a warehouse-turned-venue called “The Lab” in Houston’s historically Black Eighth Ward. When Maddie learns that the Eighth Ward is to be sacrificed for a new electromagnetic hyperway out to the suburbs, she joins “Save the Eighth,” a Black-led organizing movement. But is Maddie herself part of the problem—or part of the revolution?

Kern will speak at Houston’s Brazos Bookstore on Tuesday September 12 at 6:30 pm. Additional Texas appearances pending.

Excerpt from The Free People’s Village, Chapter 1, reprinted by permission.

7:00 p.m. – August 14, 2020

I know you want to hear about the Free People’s Village and that literal, fateful-fucking-step at the reflecting pool, but to explain why I did what I did, I have to start the story months earlier, before the tents and tear gas and stirrings of revolution, with the night of the last great party at the Lab—the night Red destroyed the Fun Machine.

I got to the house just before sundown. Even though I taught in the Eighth Ward, just a few blocks away, I always went home to change before a show. My friends would have roasted me alive for showing up to the Lab in one of my linen work suits. So after the last bell, I’d bike two miles to the G train—the only maglev station in Eighth Ward. I’d wait one or twenty minutes, depending on luck, watching the grackles argue in the live oaks around the station, feeling nervous, if I’m honest, as I was usually the only white person on the platform.

Then the G train zipped me to Midtown. After a few minutes, the old, brick cottages and shingle roofs of the Ward gave way to shiny Community towers—their tops angled and glittering black with solar panels. The landscape morphed from yards choked with invasive vines or flat-topped squares of Bermuda grass into swaying prairies, interrupted by the neatly maintained orchards surrounding each Community. Here and there, the prairie humped up in wildways passing over the maglev lines that spiderwebbed across this part of the city, with a stop for each Community and fast connections to Downtown, the Medical Center, and the Galleria. At each stop as we headed west, more Black people got off and more white people got on.

Disembarking at my Community, I dashed from the station up to my apartment on the seventh floor. Threw off my stale work clothes. Threw on thrifted cotton shirt, denim shorts, and some alligator-leather cowboy boots I’d found at an estate sale. I threw on a thick coat of eyeliner, clipped a take-cup to my belt, and then it was back to the train, back through the prairie and over the bayou, past herons spearing fish along the rocky banks, and finally back through the time warp. To a neighborhood that hadn’t changed a bit in the last twenty years of the “War on Climate Change,” except that its potholes were wider now.

Navigating those craggy streets on my pop-out bike as the sun set was no easy feat. At least I didn’t have to worry about cars running me off the road, like they would’ve in the olden days. By 2020, the only cars left in the Ward were wheelless hulks in backyards, colonized by bees and weeds, too rusted to be sold for scrap. Only suburban people or rich folks had cars anymore—and those were all shiny, hyperway-compatible electrical vehicles. The carbon taxes on old-school gas guzzlers were so exorbitant that only the richest of the rich could afford to drive them, and all the gas stations in the city had been converted to rapid battery-charging Stations.

By 2020, the only cars left in the Ward were wheelless hulks in backyards, colonized by bees and weeds … Only suburban people or rich folks had cars anymore—and those were all shiny, hyperway-compatible electrical vehicles.

Despite the treacherous pavement, I pedaled as fast as I could— acutely aware that I was a tiny white girl in a skimpy outfit. I was afraid of the clumps of old men who stood together, chatting on street corners, sipping from take-cups. Sometimes they hollered something as I sped by—nasty or nice, it felt threatening either way.

I don’t know what made me pump my legs harder though—that vague, unspeakable fear, or the deep-down knowing that I didn’t belong there. That I was an invader.

I breathed easier rounding the turn onto Calcott, spotting the Lab up ahead, silhouetted by the last of the sun’s rays. Light and loud music spilled from the old red-brick warehouse’s windows and doors, every hole in that lovely, ugly face thrown open, filled with people of every race, gender, style, and subculture you could imagine, all of us so young—young enough to have no idea what kids we all were. Barely-adults like me, plus some teens who could be my students, though they never were. Except for Gestas, people actually from the Eighth Ward never came to shows at the Lab. They had their own places. The Black kids who came to our parties had white collar parents and lived out in the suburbs or university dorms. Crossing the Ward, they probably biked about as hard as I did to get to the Lab.

Cruising to a stop in the weedy front yard, I was finally home. The throbbing bass line spilling from the front doors enveloped me like a protective force field. I breathed in the haze of weed smoke and chemicals flaring of the refineries in the distance. The sun hadn’t set, which meant that the AC wouldn’t be on. Most of the early arrivers were standing around the yard in clumps, drinking keg beer from their take-cups, throwing back their heads in laughter, flashing their jugulars at the sky.

I collapsed my bike, stored it in my bag, and shouldered my way inside, past some blondes young enough to be in my English class. It must’ve been over a hundred degrees inside, and I sweat through my clothes in seconds. The front of the warehouse had once been offices that Fish had converted—rather terribly—into apartments. I popped my head inside Red and Gestas’s place, but they weren’t there. The guitarist from Okonomiyaki Riot was lying on Red’s bed though, strumming “Blackbird” on Red’s acoustic guitar while some groupies looked on adoringly. I felt a wild surge of possessiveness. Who the hell was he to be on Red’s bed, touching xir guitar? I shoved the feeling down, reminding myself for the thousandth time that Red was not mine to claim. I was sick of these waves of intense, nonsensical jealousy.

I felt a wild surge of possessiveness. Who the hell was he to be on Red’s bed, touching xir guitar?

I wove through the crowd in the hallway between the apartments and passed through the door to the main warehouse space in the back. It was cooler in here, as the sliding back cargo doors were thrown open to the dusk air. Still, it was probably 90 degrees, and the few dozen people inside were slumped against the walls or on the curb-scrounged, greasy couches that interrupted the room. Vida was painting an armadillo wizard over a hundred scrawled tags on the back wall, and the bassist from Okonomiyaki Riot was skateboarding down the strip of empty space in the middle of the warehouse.

In the corner that was the unofficial “stage,” Fish was plugging in our amps and Red was setting up xir mic stand. I was still Fish’s girlfriend, but I’d been wondering for a long time how to extricate myself from that relationship without destroying the band. It was Red—tall and laconic, sweat-slicked black hair falling across xir eyes—the sight of Red made my heart fly off in wild, syncopated rhythms, like Gestas tearing into the drum solo at the end of “Don’t Think About Death.” It’s how I’d felt every time I’d seen Red over the past year, ever since I’d first laid eyes on xim—that cicada-filled afternoon, when xe stood in the doorway to xir apartment, twirling a red patent leather shoe by its heel.