Wind back the hours, the days and months, a year –

and out of fog, Ormonde sails like a rumour,

or a tale about how what’s too soon forgotten

will rise again – light up, awaken engines,

swing her bow through half a century,

return a hundred drifters, lost-at-sea.

From Ormonde by Hannah Lowe

The Empire Windrush is commonly believed to be the first boat to have brought post-war migrants from the Caribbean to Britain in 1948. This moment was captured by the Pathé newsreel of the famous calypsonian Lord Kitchener tentatively singing, London is the Place for Me.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

Since 1998 – the 50th anniversary – the ship’s arrival has been commemorated in hundreds of public accounts, and the name Windrush has become symbolic of the generation of Caribbean people who arrived during this period. It is the first moment of black British experience to become mainstream British history.

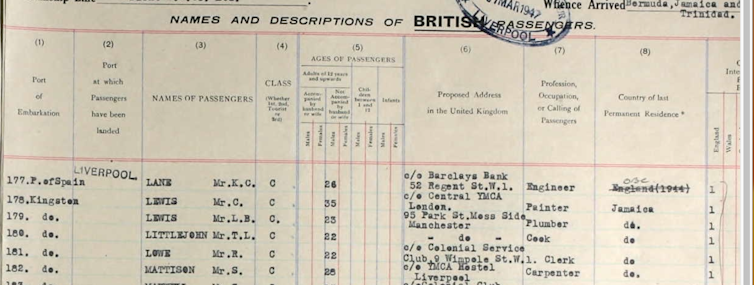

But far less is known about the two ships that arrived before the Windrush, carrying smaller but still significant numbers of migrants: the SS Ormonde, which docked in Liverpool in March 1947, carrying 108 passengers, and the Almanzora, carrying around 200 passengers, which arrived in December of the same year.

My father Ralph Lowe, a clerk by trade, was on the Ormonde, which led me in 2014 to publish a book about it, containing a series of poems about “the other ship” that has largely been forgotten, along with the Almanzora.

Forgotten voyages

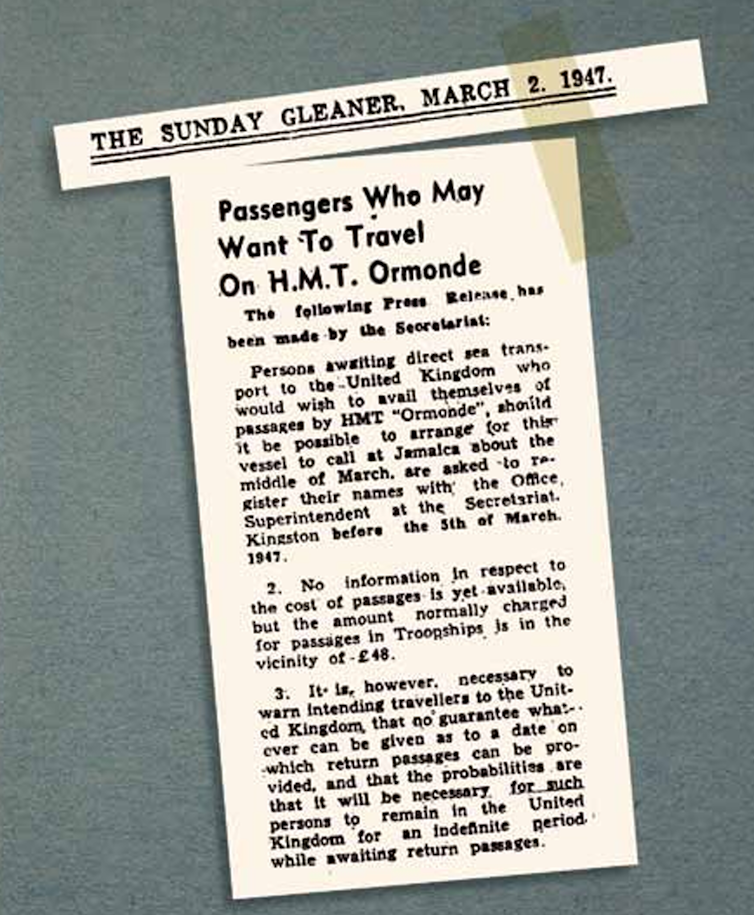

Like the Windrush, these ships were returning troopships. And like the Windrush, passage on these ships was advertised in Jamaica’s national newspaper, the Kingston Gleaner.

Ormonde’s arrival is mentioned briefly in the Evening Standard on April 1 1947, and in the Times on April 2 1947, concerning the trial in Liverpool of its 11 stowaways. But the Almanzora was not mentioned at all in the press at the time, a fact bemoaned in 2008 by one of its passengers, Alan Wilmot:

… [Our arrival] wasn’t like the Windrush – there was no publicity for us. It was a case of every man for himself.

The Jamaican poet James Berry, who became a voice of the Windrush generation, also arrived in Britain on board the Almanzora. In his poem, Beginning in a City, from 1948, he wrote:

Stirred by restlessness, pushed by history, I found myself in the centre of Empire.

A young man’s journey

My father Ralph kept a notebook about his early life and wrote of his plans for travelling to England:

I soon found out that you could book a passage on ships bringing back servicemen who had fought in the second world war. So I duly booked my passage on the SS Ormonde paying the princely sum of £28 to get to England.

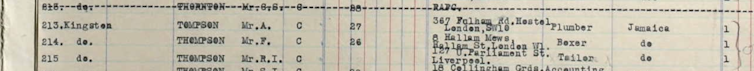

Before his death in 2001, he told me that he had travelled to London from Liverpool with two boxers he had befriended on the boat. It was quite wonderful, many years later, to find both his name (R. Lowe), and the names of the boxers (Thompson) on the Ormonde’s passenger list.

A few recent accounts that do discuss these earlier voyages include Robert Winder’s Bloody Foreigners which acknowledges that the Windrush was not “the first ship in this story”. American author Tony Kushner’s study of migrant journeys also includes a discussion of these two ships, considering whether it is London’s dominance in migration history that might account in part for the sustained focus on the Windrush over the Ormonde or Almanzora.

The Ormonde docked at Liverpool and the Almanzora at Southampton – both ports of equal or more significance than London in terms of the numbers of ships that docked there. And they are also equal regarding their importance to migration history, but certainly less discussed.

Why Windrush?

If the arrival of Windrush close to London might account for its fame, so too do numerous other historical factors. Windrush carried 492 passengers, a spike in numbers commonly attributed to the newly passed 1948 Nationality Act, which awarded colonial subjects a new status: “citizen of the United Kingdom and colonies”.

The boat was met at Tilbury Docks by officials from the Ministry of Labour and the Colonial Office. One, called Ivor Cummings, was the son of an English mother and Sierra Leonan father.

Cummings helped to organise accommodation for many of the passengers in the former air-raid shelter beneath Clapham Common South underground station. Also present were journalists and photographers, resulting in numerous newspaper accounts, the Pathé newsreel and the small, but now iconic, number of photographs of the ship.

Read more: Ivor Cummings: the forgotten gay mentor of the Windrush generation

Unlike the Windrush, the Ormonde and the Almanzora arrived without ceremony to their respective ports. There was no meeting committee, no press and no assistance for their passengers.

In fact, the story of the Empire Windrush was atypical of voyages made at this time, and quite different to the ships that came before or immediately after, which carried far fewer migrants. In the 1950s, at the height of this period of migration when ships regularly sailed a direct route from the Caribbean to Britain, passengers were left to fend for themselves on arrival.

Many ships of this period are intricately tied to the machinations of the British empire and the second world war. The SS Ormonde went on to transport British orphans to Australia under the controversial child migration programme, while the Windrush (a German warship until it was seized by the British in 1947) later sank in the Mediterranean, bringing home servicemen from Asia.

Both the Ormonde and the Almanzora were eventually scrapped in Scotland (the Ormonde had been built on the Clyde in 1917), but their post-war migration legacy has begun to feature more often in recent discussions of this period. The stories of these ships are evidence of how “history” is so often a complicated and nuanced process of selection – and omission.

They tore the Ormonde up in ’52

for scrap. I google what I can. If you

were here, you’d ask me why I care so much.

I’d say it’s what we do these days Dad, clutch

at history. I find old prints – three orphans

on a deckchair squinting at the sun; a crewman

with his arm around a girl, both smiling, windswept;

a stark compartment where you might have slept…

From Shipbreaking by Hannah Lowe

Hannah Lowe does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.