Some of us have never known a time when O.J. Simpson wasn't onscreen somewhere or part of the cultural conversation. Starting in 1975, Simpson was the cheerful and dashing personification of Hertz's efficient car rental process, leaping over stanchions and half-walls, as well as flying through airport concourses — all while wearing a three-piece suit and never breaking a sweat.

Like Simpson, everyone is selling something to make it in this world. Simpson's natural talent was selling himself, and he was one of the best at doing so — until he became one of the most reviled people in America. Understanding this makes Simpson's legacy a lot less complicated in the influencer era, where not only Kim Kardashian but everyone else is encouraged to present themselves as a brand and capitalize on whatever products they can associate with their thoroughly curated personalities.

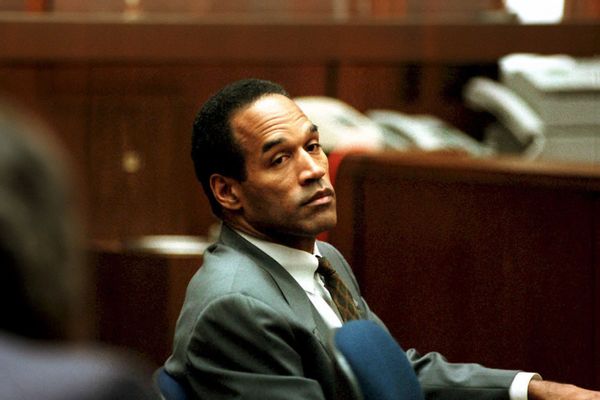

Simpson, who died Wednesday at the age of 76, is mainly remembered as one of the greatest running backs of all time who was later acquitted of two murders that many remain convinced he committed.

But years before he was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame, before he had signed with the Buffalo Bills and before he had even graduated from the University of Southern California, Simpson wanted to be eternally famous. In the darkest interpretation of that desire, he got his wish.

Simpson was led by the public's perception, or his interpretation of it, that enough ubiquity and money places a person beyond reproach. Before his 1994 fall, his success seemed to bear out that hypothesis.

Simpson's singular combination of athleticism and handsomeness attracted many more endorsement deals, attaching his name to everything from cowboy boots to chicken and beverages — including, predictably, an orange juice brand. But if you appreciate cosmic irony, watch his first TV appearance on an episode of "Dragnet 1967."

Simpson had no lines to distinguish himself from the group of men being courted by Joe Friday to join the police force. Nevertheless, his character sits there on the far right, appearing to listen intently as the TV detective makes his case.

"I won't talk about the contribution you'd make to society as a policeman. I won't mention the satisfaction you'd receive helping your fellow man, of being a vital, important, active member of your community. Maybe those things are important to you, maybe they're not. That's for you to decide," Friday tells the group that includes Simpson's character. "But if you are interested in a job with a future that's exciting and far from routine, a career that offers unlimited opportunities, as well as guaranteed security, I sincerely suggest you consider joining the department."

There are lines that ricocheted back in time to haunt Simpson — and everyone who lived the 1995 trial that forever altered popular culture and media. That "Dragnet" pep talk, however, isn't one of them.

Instead, we recall simpler ones, such as "If it doesn't fit, you must acquit" or — as a tidy row of Girl Scouts yelled at Simpson as he sprinted past them in one of his earliest Hertz commercials — "Go, O.J., go!"

More than a creature of American celebrity worship, Simpson was a product of as-seen-on-TV ubiquity. After retiring from the NFL in 1979, Simpson starred in an array of TV movies, as well as co-starred in 1988's "The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!" with Leslie Nielsen and each of its sequels. While he was still playing professional football, Simpson appeared in the 1977 miniseries "Roots" as an African tribesman and hosted a 1978 episode of "Saturday Night Live."

In 1975, the ad executives responsible for hiring Simpson to represent Hertz had just seen him win the third round of the ABC "Wide World of Sports" special called "The Superstars," an early version of a reality athletic competition.

Between such appearances and those Hertz ads, which ran heavily through the '80s, along with the assortment of TV and movie roles that followed, Simpson won millions of fans who never watched him play or cared about the sport.

He also forged a path for high-profile athlete endorsements long before Nike welded its destiny to Michael Jordan, Muhammad Ali hawked Bulova watches, "Mean" Joe Green lovably smiled in that 1979 Coke ad or Shaquille O'Neal lent his image to promoting anybody who threw a check at him.

Simpson expanded his filmography while he played in the NFL, but nothing hurtled him toward massive fame more efficiently than those endorsements. By the time he divorced Nicole Brown Simpson, in 1992, according a 1994 Washington Post story, he was making more than $1 million a year — $550,000 of which came from Hertz.

Knowing what we know now, though, that "Dragnet" monologue is shaded in levels of bleak irony. Studious examinations of Simpson's life, the best of which is ESPN’s five-part 2016 documentary "O.J.: Made in America," confirmed that he desperately wanted to be a vital, important active member of his community, only not the one to which Joe Friday referred.

As Simpson's renown grew, he insulated himself more and more deeply in whiteness, as "Made in America" put forth. The Kardashians are stars and billionaires today, in part because their father, the late Robert Kardashian, was Simpson’s best friend and served on his legal team, one of the many white celebrities who rallied around Simpson following his 1994 arrest.

That "Dragnet" episode aired around the same time that Simpson won the Heisman Trophy, in 1968, and marked a crossroads for Simpson that figured into his negotiations to join the Buffalo Bills. An appearance in the pilot episode of CBS's "Medical Center" could have launched an acting career, but the Bills guided Simpson into their camp with a $650,000 contract that paid out over five years.

Wealth is relatively easy for a professional athlete to come by these days, but at the time, that figure represented the highest payout in professional sports. Lasting fame, on the other hand, is never as certain, especially back in the '70s and '80s, unless one abided by a set of unspoken rules.

Simpson knew this as early as 1976, when The New York Times ran a story rhapsodizing over his shocking success as Hertz’s pitchman, part of a $12.6 million advertising campaign. It read:

Mr. Simpson seems hardly surprised at his success as a promoter. "People identify with me and I don't think I'm that offensive to anyone," he said recently, as he leaned back in a chair in one of the stadium's offices and watched the snow falling outside.

What, if any, impact has Mr. Simpson's being black had on his effectiveness? "People have told me I'm colorless," he said. "Everyone likes me. I stay out of politics, I don't try to save people for the Lord and, besides, I don't look that out of character in a suit."

One wonders if the story's headline might have been phrased differently had it come out after "Roots," which debuted a couple months later. "Hertz Is Renting O.J. Simpson And They Both Stand to Gain," it declared.

Probably not. Times have changed, as they say, but not that much.

Regardless of whether that wording was intentional, the dual implication of a corporation leasing a Black man for profit was one of those demonic details about race that most Americans, Simpson included, pretended not to see well into the '90s.

Our sight was temporarily restored after Simpson was charged with murdering his ex-wife Nicole — a white woman — and her friend, Ronald Goldman, on the night of June 12, 1994.

Ryan Murphy's Emmy-winning 2016 limited series, "The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story," opens with footage of Rodney King's 1991 beating and the subsequent 1992 riots after the policemen who assaulted King were acquitted.

If America, like Simpson, had deceived itself into thinking that it, as a nation, had moved past racism and inequity, footage of Los Angeles' long-simmering rage exploding through its streets proved otherwise.

Simpson's arrest and televised trial exposed other aspects of that divide, which Salon's executive editor Andrew O'Hehir summarized with clarity in his 2016 analysis of "O.J.: Made In America." For one, Simpson's trial exposed the lie of white corporate media's promotion of a post-racial America. Both Newsweek and Time magazines featured Simpson's mugshot on their covers in 1994, but Time darkened the image, playing into stereotypes of Black menace while claiming aesthetic reasons for its choice.

Years later, a colleague would refer to that marker of Simpson's reversal of fortune as his "There and Black Again" moment. There is truth to that statement: As soon as the ratings estimates clocked the live audience for Simpson's slow-motion Bronco getaway at 95 million viewers, his grip on the media was lost forever.

Onlookers stood on overpasses or streets holding handmade signs screeching a familiar cheer back at him — "Go, O.J., go!" — but this time in jest, as if his connection to a double homicide was not to be taken seriously.

Crashing in Simpson's guest house injected a second wind into the flagging career of Brian "Kato" Kaelin, whose name came up in late-night monologues enough to earn him cameo appearances on shows like "MADtv," along with movie appearances and celebrity reality show stints.

Court TV grew from a niche network into a wall-to-wall crime case, as it began providing content to other outlets. Lyle and Erik Menendez's first trial in 1994 proved the public's appetite for watching court cases starring young, rich and handsome men who killed their parents.

Simpson's level of fame on top of similar circumstances, along with surfaced reports of spousal abuse long ignored by the Los Angeles Police Department, made the wall-to-wall trial coverage more addictive than a soap. An estimated 140 million tuned in to Simpson's acquittal verdict when it was announced live on Oct. 3, 1995. MSNBC and Fox News both launched in 1996.

A little more than a year before his trial, Simpson made an action pilot called "Frogmen," playing the leader of a Navy SEALs team. NBC was on the verge of picking the show up but reversed course after its star was charged with two murders.

We may never know whether Simpson might have polished and relaunched his star after a time if he had performed any remorse instead of tooling around in a golf cart days after his acquittal, lamely vowing to hunt "the real killers." Audiences have an unsettling habit of looking past the worst sins committed by their "problematic faves," even after they have been convicted in a court of law — and especially if they can convince their followers that they were somehow wronged by a system set against them.

Though Simpson was acquitted of Brown's and Goldman's murders, he was found liable for their deaths in a 1997 civil suit verdict in which he was ordered to pay $33.5 million in damages. From there, Simpson leached from the bones of his notoriety by attempting to publish a book called "If I Did It," an alleged hypothetical description of the murders he maintained he hadn't committed. He also recorded a Fox special to accompany its publication. Fox pulled both in 2006 after more than a dozen affiliates refused to air it.

The TV special finally aired in 2018 as "O.J. Simpson: The Lost Confession?", while Goldman's family released the book after securing the rights to its publication in order to recoup some of the civil damages they're owed. Most of that money hasn't been paid out.

But that disgrace was preceded in 2007 when Simpson produced exciting new footage that led to his arrest and subsequent conviction in 2008 on armed robbery and kidnapping charges for stealing sports memorabilia and collectibles in Las Vegas.

Following his 2017 prison release, Simpson tried to recapture some of his media glory in 2019 by joining Twitter, limiting his public expression to 280 characters and some of the smallest squares of video available.

One might see that as his means of helping his fellow man, as some "Dragnet" writer suggested his fictional justice field recruit might do way back when. But his late-in-life actions ensured Simpson's infamy would outrun all of his legitimate accomplishments as a record-setting athlete, sports endorsement pioneer and all-around telegenic performer.

Simpson was trying to score points with a public who no longer saw him as a football legend, an affable movie star, a trusted network commentator, colorless or inoffensive. A monstrous crime irretrievably changed our impression of him nearly 30 years ago, and he never made much of a case for us to turn from that channel.

"The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story" streams on Hulu. "O.J.: Made in America" also streams on Hulu with an ESPN+ subscription.