A group of young footballers are sitting together in a canteen, talking about “girls” and the game in the way young footballers do, when the conversation turns to something deeper.

“Let me just ask you, what do you imagine freedom to be,” one goes to the table. “Let me have a go,” another responds. “I think freedom means maybe not being under slavery but having access to everything, your movement, free expression.”

“So many immigrants are coming to Qatar to work in search of greener pastures, but maybe a couple of them are not finding this greener pasture. They are staying in Qatar against their will, not directly like you’re being enslaved here. But, it’s like, you can’t go back, so you just stay and work for maybe the small salary.”

Another interjects: “Modern slavery.” “You can call it that.”

The men go on to talk about how they miss just running on the beach, food from home, and even being able to go on a date.

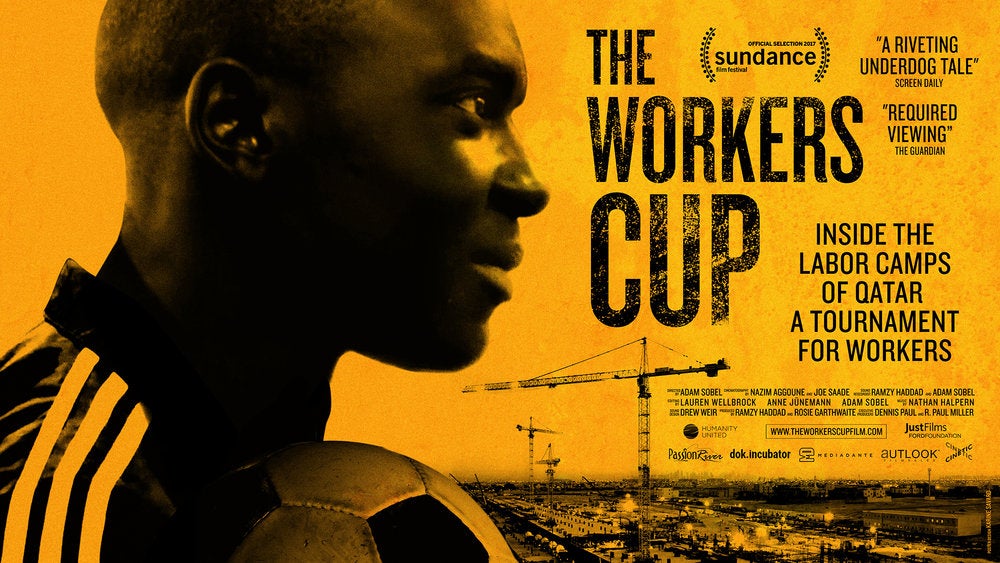

As you can probably guess by now, this certainly isn’t the England players, or any other Nations League squad complaining about four fixtures in this international break. It is actually a scene from a superbly moving documentary called The Workers Cup, one that should really be shown to every team going to Qatar in November. That’s all the more pressing as the England squad prevaricate on what to do next as regards human rights abuses, and Harry Kane talks this week about collective plans with captains from other nations.

That stance is actually understandable to a point since one of the issues with so much general discussion about human rights in Qatar is that numbers and words only go so far. There is a point where they stop having any impact.

The tragic beauty of Adam Sobel’s documentary, which is available on Amazon for a cheap rental fee, is that it cuts through all of that with images and emotion. It presents the true significance of all that coverage, and it would be very difficult for anyone to watch it and not be moved to do something – especially if you are going to be involved in the World Cup.

This is the thing with footballers, too. As the pandemic and so many England campaigns have shown, they are more than willing to help when they are presented with the true effect of social problems. It is why the FA should show Gareth Southgate’s squad this documentary.

The film covers a group of migrant workers for a company called GCCC in Qatar, who are allowed a rare opportunity to experience something like normal life by playing in a football tournament between different organisations.

That is all the more poignant for one of the main subjects of the documentary, 21-year-old Kenneth from Ghana, since he was given the impression by a recruiting agent that he would be transferred from the construction job he was signing up for to a professional football club when he got to Qatar.

There’s a line from another worker, Padam from Nepal, that sums up the situation for pretty much all of them here.

“When I discovered the reality it was too late.”

That reality, when spelt out, is genuinely like something out of a dystopian future. So many migrant workers were lured to Qatar under false pretences, where their desperation was exploited, only to then find themselves in circumstances that really resemble a prison camp.

The general details of this are now well-rehearsed. They have to hand over passports. They are left in debt by exorbitant recruitment fees, ensuring the companies have almost total control of their lives. They can’t even leave the camp without permission from their superiors, which is so rare.

One worker, Paul from Kenya, forlornly talks of wanting to go on a date with a woman he met on Facebook.

The actual lived experience as shown in the film is even sadder, and one of many reasons it is worth watching the documentary. There are so many emotionally affecting vignettes that show how bleak it all is.

“With all this struggling, what’s the good of our lives anyway?” Paul asks.

There’s then quite a description of Qatar, as the camera pans over the cityscape that has been given such prominence in glamorous World Cup promotions.

“It is hell and it is only for rich people.”

Many of the workers deal with extreme loneliness, only able to talk with loved ones – thousands of miles away – on their mobiles. Padam, like so many, was there to try and raise money for his family but in his position as a lowly office worker, he was not allowed to bring his wife over from Nepal. In order to earn the money his family expected he was working all overtime hours he could take and had only seen her once in eight years of work in Qatar.

“I missed my family so much.”

At one point, Paul imagines a comment from a future grandson.

“You don’t even own a thatched house yet you built that stadium, you are useless.” The men meanwhile talk matter-of-factly about workers who died in the construction of such buildings.

It illustrates how the mental health conditions are as much of a problem as the run-down physical conditions of the camp. Severe depression and suicidal tendencies are rife.

In one shocking moment, a co-worker of the team is attacked by a roommate in their shared dorm in the middle of the night, his leg cut with a blade. The roommate basically did it to escape, as he knew such an act would likely see him deported.

The most remarkable aspect of this, however, is that all of them – even the co-worker attacked – are calm about his actions because they could understand the mindset. The man just wanted out.

It fortifies a constant thought during the film, which is over the cost of this World Cup. How is Qatar 2022 worth this? And yet it is football itself that gives the men self-respect and a brief sense of normal life again.

One team talk features an impassioned call to show “the white people we are doing perfect”, that “we are not slaves”, that “we are better than anybody”.

The scenes around the matches are uplifting because of everything else around the camp, as the players command the support of viewers. You end up looking at it like you would any match involving your own team.

Out of that, it would be easy to imagine a certain type of football bureaucrat taking completely the wrong message from the film, about the universal power of the game.

The problem is that the dark side of it all is never far away.

In one big match, the team become suspicious that another company side is made up of wealthy staff members, rather than fellow workers. The other organisation win, the Workers Cup having possibly been appropriated for the benefit of those forcing them to live through such conditions.

The competition itself is devised by the organising committee of Fifa 2022 for companies wanting tenders for the World Cup. It is then used by them to promote their worker welfare, to win tenders and recruit more workers.

It’s quite a metaphor. There are more.

After one game, a debate breaks out among the team about how African workers are constantly picked to start matches over those from South Asia.

One of the African players then breaks down crying as he counters by saying a teammate tells him “I belong to the forest, because I am black”. His co-worker pleads it’s just joking.

It is heartbreaking, and reflects a deeper point.

Professor Tendayi Achiume, the UN’s special rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, has already described how the entire migrant worker structure is built on “serious concerns of structural racial discrimination against non-nationals in Qatar”, with less human rights protection for “south Asian and sub-Saharan African nationalities”.

Within that, Amnesty studies have found that there is an extra level of pay discrimination among workers on the basis of nationality, race and language.

“They pay us by nationality,” one guard who works at the offices of a sporting body told Amnesty in a recent report on the security sector. “You may find a Kenyan is earning 1,300 [riyals], but the same security from the Philippines gets 1,500. Tunisians, 1,700.”

To give a further illustration of the kind of control the workers were under, it took the filmmakers three months to earn their trust due to suspicion of fellow workers sent to oversee the filming, and this – shockingly – at what was considered an “A-star camp” where the company owner appears to have been mindful of the conditions.

It should be acknowledged that most of the film was done over 18 months from 2014 – and released at Sundance Film Festival in 2017 – but that raises an even more important point in itself.

Eight years on, and despite so much talk of reform in Qatar, very little has actually changed. Amnesty and other human rights groups such as FairSquare have repeatedly criticised the state for introducing legislation but not overseeing any real change in practice. The filmmakers behind The Workers Cup say that the men in their film who remain in Qatar, and those who are not seen so much on camera, are still experiencing all the same problems you see in their film. They are also crucially, still on the same wage as they were eight years ago of approximately $200 a month.

Workers remain acutely vulnerable to forced labour, and it is far too easy for businesses to get around the new laws.

It all points to the scale of the problems at this World Cup, which even Southgate described as “quite overwhelming”.

He was criticised for that, but it is a truth that there is so much that it can be very difficult to take in. That is precisely why the human rights groups finally came together last month to agree on one simple and obvious call ahead of the World Cup.

That is for those in football to back the establishment of a Migrant Workers Centre in Qatar, and pressure Fifa to compensate migrant workers and their families.

There has not yet been a move on this from the FA, despite a letter to the federation about it, but both Southgate and Kane spoke on Monday of how they are all trying to come up with a “collective standpoint”.

It’s just that process has been going on for some time now, with time also running out for players to use their considerable leverage with this World Cup.

Watching The Workers Cup would undeniably speed things up considerably.