There is a note of skepticism in Jayson Tatum’s voice. “That’s a real picture?” he asks, peering down at the Jan. 9, 1956, cover of Sports Illustrated. Indeed, photography from that era can resemble a well-painted watercolor or something that today might be spit out by an Instagram filter, but the image of Boston Celtics icon Bob Cousy turning the corner on Fort Wayne Pistons big man Larry Foust is, in fact, legit.

“Nice sneakers,” Tatum says, noting Cousy’s black Chuck Taylors, which sold for around eight bucks. Tatum recently revealed he owns a pair of Nikes that sell for $8,000.

Drafted by Boston in 2017, Tatum knew little of Cousy. Or of the Celtics, really. He grew up in St. Louis, a city the NBA abandoned long ago. Kobe Bryant was his basketball role model. He recognized the names of some of the Boston greats—Cousy, Bill Russell, Larry Bird—but not much else. It wasn’t until ESPN released its documentary on the Celtics-Lakers rivalry in ’17 that he realized Cedric Maxwell was more than a radio analyst. He met Bird for the first time last February, during NBA All-Star weekend. “I was in awe,” Tatum says. “That’s the guy that you aspire to be when you wear this uniform.”

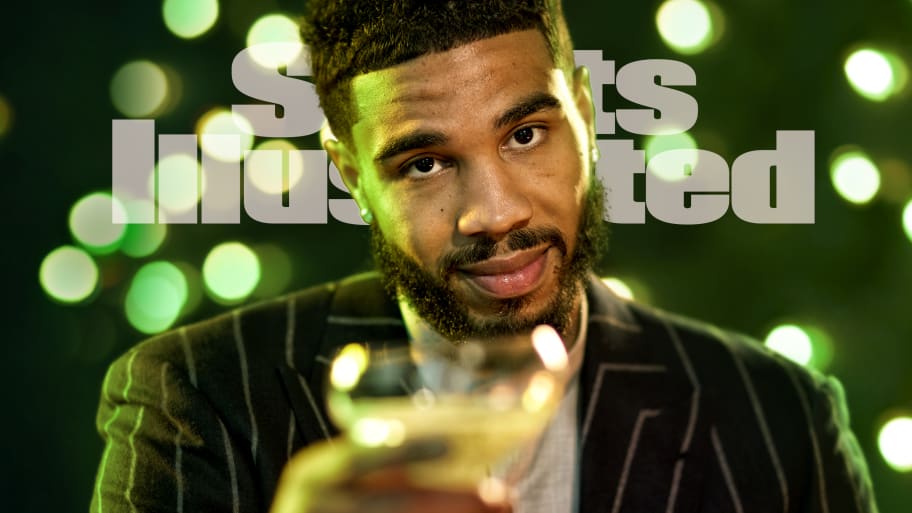

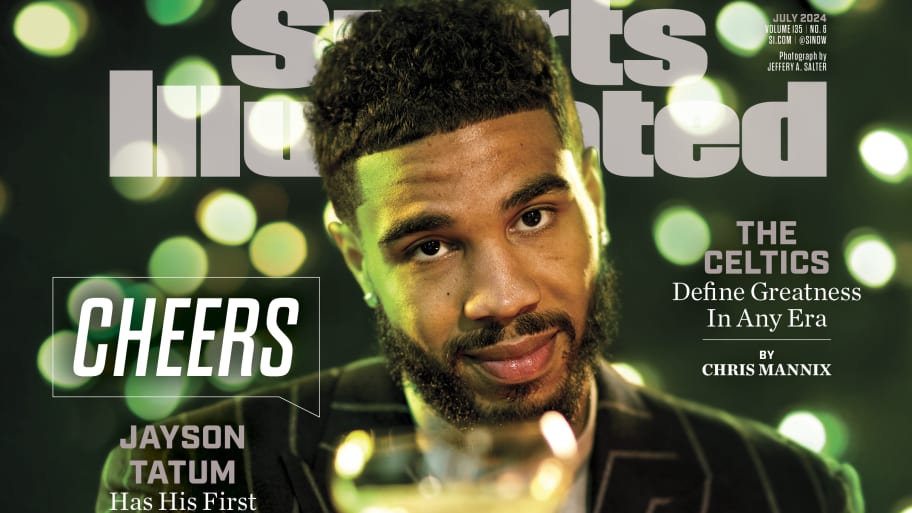

Tatum is studying the old issue during a break in his own photo shoot, the latest NBA athlete on the cover of SI admiring the first player from the league to be featured there. Cousy, sheepishly, admits he doesn’t remember the cover. “Wasn’t SI a hunting and fishing magazine for a while?” Cousy asks. Well, yes, early editions of SI did feature a fisherman’s digest and articles about African safaris. But there was plenty of mainstream sports coverage, too, including barrels of ink spilled on the Celtics, who, after knocking off the Dallas Mavericks in five games to win their 18th championship, moved past the Los Angeles Lakers on the NBA’s all-time title list while slipping ahead of the Montreal Canadiens for the most championships in SI’s 70-year history. “I do remember SI being a big deal,” Cousy says. “And I did like being on covers.”

[ Buy now! Jayson Tatum on Sports Illustrated’s July 2024 cover | Order SI's NBA championship digital commemorative issue ]

Cousy is a realist, or at least sounds like one. Physically, he is healthy, or as healthy as a soon-to-be 96-year-old can be. He doesn’t move around much these days, his limbs weakened by back surgery and a mild case of diabetes that have left him largely wheelchair-bound. Every Thursday his daughter, Ticia, wheels him out of the modest Worcester, Mass., home he bought 61 years ago and drives him to a nearby country club, where Cousy sips on a couple of Beefeaters on the rocks and remembers better days. Internally, everything’s functioning, or so says his doctor, who makes monthly house calls. “He tells me, ‘Cous, you have the heart and lungs of a 20-year-old,’ ” Cousy says. It’s everything else that’s falling apart which, for a Hall of Fame point guard who spent 14 seasons effortlessly zipping up and down the floor, can be maddening. In 1956, the article accompanying Cousy’s SI cover had the headline BASKETBALL’S GENIUS. Yet to Cousy, the image of his 27-year-old self deftly dribbling through traffic is nearly unrecognizable. “I’m in double overtime of life,” he says.

There is still strength in Cousy’s voice, which rises when he starts talking about the past. “All I’m doing is sitting here all day on my fat ass thinking about the old days,” he says. He was 18 when he boarded a train from New York to Worcester to attend Holy Cross, and he never left the area. When the Celtics acquired Cousy in 1950—via a dispersal draft, after Cousy refused to report to the Tri-Cities Blackhawks when they declined to pay him the $10,000 per season salary he demanded—he became a commuter, driving the 47 miles between Worcester and Boston every day. “I’d get back here, lock the gates, go into my loner routine, not pick up the phone,” Cousy says. “And I avoided 90% of the crap that I would’ve had to put up with for all this stuff.”

The “stuff,” as Cousy calls it, was outsized success: 13 All-Star appearances, 12 All-NBA honors, the 1957 MVP trophy. For seven years he was the offensive yin to Russell’s defensive yang, whipping never-before-seen passes on one end while Russell swatted away shots on the other. He won six championships in Boston, though on his trophy shelf there is little commemorating them. He remembers getting one ring. Definitely not six. The only one on his shelf is one the Celtics gave him in 2008 for his role as a broadcaster. He got a set of golf clubs after one title. Some jewelry for his wife, Missie, after another. Besides, he’s still preoccupied by the one he didn’t win. “In 1958, Russell stubs his toe,” Cousy says, referencing the ankle injury Russell suffered in that year’s NBA Finals. “It would have been seven. It should have been seven. But I’ll settle for six.”

He’s proud of these accomplishments. He knows the perception: that the Celtics played in a slimmed-down league, that the task of winning titles is far more difficult today. In 2022, JJ Redick, now the Lakers coach but then an analyst with ESPN, criticized Cousy’s success, saying it came against plumbers and firemen. Cousy isn’t about to compare eras, but he insists there is a counterargument. “There were only six teams,” Cousy says. “So whatever talent was available, it was more concentrated. In that sense, winning was tougher.”

From afar, Cousy marvels at today’s game. The size, the speed, the skill. He doesn’t love the proliferation of the three-point shot—“I don’t like it as the first option,” Cousy says—but he gets it. And the money. Yeesh. In 1954, Cousy helped form a player’s association. The exhibition schedule was out of control—teams were playing as many as 23 games, a “full college season,” he says—and salaries weren’t growing. “We needed a seat at the f----ing table,” Cousy says. The union had little leverage back then; attendance was around 4,000 for most games and the idea that games could be regularly watched on television sets was a fantasy. In five years as union president Cousy’s greatest accomplishment was getting owners to raise per diem from $5 a day to $7. “I was a hero for that,” Cousy says. In ’63, Cousy was the NBA’s highest-paid player, at $35,000 per year. Last summer, Jaylen Brown signed a five-year extension worth north of $50 million a season. “I held out for $10,000,” cracked Cousy, “so Jaylen could hold out for [$304] million.” Tatum surpassed that shortly after the Finals with a $314 million deal.

Cousy has an affection for the well-compensated group. Some of it is their journey: Before this season, the Celtics made a habit of coming up short in the postseason. Cousy’s Celtics failed to so much as reach the Finals his first six seasons.

Some of it, most of it, is legacy. He doesn’t usually stay up past 8 p.m., but he was awake till nearly midnight to watch the team celebrate. Championships are what still tether Cousy to the franchise and to stars like Tatum, what connects a shifty 6' 1" point guard from Holy Cross to a 6' 8" three-point shooting forward from Duke. Days after the title clincher, a producer friend of Cousy’s asked him to record a message for the team.

“I just said, ‘Job well done,’ ” Cousy says. “But I hope you appreciate the legacy that you represent. One of the things I’m most proud about is that we started a unit. Red Auerbach and I were the first, we stuck together, then got a guy named Bill Russell in 1956, and finally rang the bell and won. That unit went on to win 11 freaking times. If you want to talk legacy, the Yankees, Green Bay [Packers], Montreal [Canadiens], they all have great legacies. None of them like the Celtics.”

Over the years Tatum has immersed himself more in Celtics culture. He’s grown close to Hall of Famer Paul Pierce, who was a frequent workout partner in Los Angeles last summer. “I literally saw Paul every day for six straight weeks,” Tatum says. He’s friendly with Russell’s widow, Jeannine. A few months after Russell died in 2022, the two crossed paths at a game. “I remember her telling me how much he enjoyed watching us play and how proud of me he was and how much he supported us even later in his life,” Tatum says. “Even when he wasn’t as talkative, he could still watch and see things. She just kept saying how proud of us that he was.”

As familiar as Tatum became with Celtics greats, he never felt like one of them. Statistically, Tatum is on a path to be one of the most prolific. Maybe the most. At 26, he’s already in the franchise’s top 20 in scoring, rebounds and assists. Only Bird and Pierce have racked up more points in their first 500 games.

But success in Boston isn’t based on numbers. It’s about banners. And as the failures piled up—three conference-final losses and a six-game flop to the Golden State Warriors in the 2022 Finals in Tatum’s first six seasons—doubt slowly crept in. In the weeks after the loss to the Warriors, Tatum admitted to a full-blown crisis of confidence.

“That was the first time where I thought, I don’t know, maybe I’m not one of the guys that can be the best player on the championship team,” Tatum says. “Because it was so hard to get to the Finals. And we still didn’t win. Getting there, that was the hardest thing I ever had to do. I was drained. That summer I had moments thinking that maybe you have to be a legend to win a championship. And there were moments where I wondered if I was going to be that guy, just because of how hard it is.”

Tatum can’t point to a specific moment that pushed him past it. “Time heals all,” he shrugs. So, too, do trades. Last offseason, after a disappointing conference finals loss to the Miami Heat, the Celtics shook things up. Marcus Smart, Robert Williams and Malcolm Brogdon were out. Jrue Holiday and Kristaps Porzingis were in. Holiday added versatility to an already stingy defense. Porzingis, a 7' 2" floor spacer, helped power a historically good offense.

The result was a 64-win season and a franchise-best 16–3 run through the playoffs. “The toughest part about winning this championship is that Smart isn’t here and Rob isn’t here,” Tatum says. “But I’m so happy that we have Jrue and KP. Those guys obviously took us to the next level.”

As did Brown. Few teammate dynamics have been as scrutinized as those of Tatum and Brown. Drafted a year apart, they had quick success, making the conference finals in two of their first three seasons together. Brown, though, constantly found his name in trade rumors, the result of a run of star players (Kawhi Leonard, Anthony Davis and Kevin Durant) becoming available and the flexibility the Celtics had to acquire them.

Meanwhile, the relationship between the two stars has been nitpicked incessantly. A rough stretch can lead to a media colonoscopy. Hell, even a good stretch. After Brown was named MVP of the conference finals, ESPN used video of Tatum applauding—apparently not emphatically enough—to suggest that the two weren’t really close. “Like I wasn’t happy for him?” Tatum says. “Yeah that was tough. Because then we had 10 days off. I was just like, ‘F---, can we start playing?’ ”

Tatum will cop to some missteps over the years. But he insists he never wanted Brown to be traded. “Most stars don’t make a conference finals until they are 27, 28,” Tatum says. “We were doing it when we were 19, 20.” He does admit, however, that he could have been more vocal.

“I’ve always told him that maybe I could have done a better job of voicing my feelings in the public eye,” Tatum says. “He always knew that I wanted him here. I would always tell him like, ‘Man, I don’t get involved with any of those talks.’ I never went to [Celtics president of basketball operations] Brad [Stevens] or went to any player like, ‘Yo, I want this guy in, I want this guy out of here.’ I show up and I want to do my job and play basketball. And looking back on in those moments, I didn’t know how that could affect somebody, because I was never in that situation. I feel like maybe I could have done a better job of publicly saying, ‘No, we don’t want anybody, we want JB.’ I just was always like, ‘I want to stay out of it.’ ”

Over the years, Tatum has often been first to collect the accolades: All-Star, All-NBA. As teammates, they are friendly. As high-level wing players, they are, at times, competitors. Tatum recalls a stretch during the 2019–20 season, when both knew they were battling for one All-Star spot. Tatum got it. “And I knew he was happy for me,” Tatum says. “But when you are a competitor, you want what’s in front of you.” Similarly, Tatum wanted Finals MVP this year. But to see Brown get recognized, Tatum says, “made me genuinely happy.”

“I feel like he has gotten a short end of the stick, whether it’s All-Star selections or All-NBA,” Tatum says. “I feel like he, in a sense, made up for some of those shortcomings that people didn’t vote him for. I was happy that he got it.”

The criticism has quieted now. The trade chatter is gone. Tatum and Brown are locked up for the foreseeable future. It’s not exactly the yin and yang dynamic Cousy and Russell enjoyed, but during the postseason Tatum led the Celtics in points, rebounds and assists. Brown distinguished himself with his defense on Luka Doncic in the Finals.

“We’ve figured out that we need each other,” Tatum says. “We have learned how to coexist. And we know we need to be the best version of ourselves in order for all of this to work. We weren’t necessarily the best playmakers early in our careers but we developed into guys that really bleed the game. We want to be a great example of guys that play on both ends as a floor and guys who are the best teammates that we can be.”

Days after winning the title, the reality of being a champion was still settling in. Tatum willingly—eagerly, even—accepted picture requests at restaurants and grins now at the golf course when he’s called “champ” on the tee box. The duck boat parade through Boston, says Tatum, “was the best experience of my life.” It’s even brought out a little swagger. Before the parade, Tatum was asked about Boston’s celebratory trip to Miami after the Finals. Former Celtic Brian Scalabrine, now a broadcaster, noted the team has had some hard-fought trips to South Florida. Responded Tatum, “They are all easy.”

“It’s like you have that window of nobody being able to tell you anything,” Tatum says. “You are the best team until somebody says otherwise.”

For Boston, that could be awhile. In the pursuit of parity, the NBA has worked to collectively bargain superteams out of existence, establishing punitive tax penalties for the free spenders. And it’s worked: In the last six years, there have been six different champions.

Boston, though, could buck that trend. The Celtics’ top eight rotation players are all under contract next season. Chronologically, Tatum and Brown are just hitting their primes. The days of double-digit title runs are long gone, but Boston is well-positioned to win a couple more.

“When you win a championship, you think about all your favorite players,” Tatum says. “They have that moment. This is what makes them, those guys that they win on the highest level. They did it multiple times. So in a weird way, yeah, I have thought about, man, you can be one of the greatest basketball players ever in some capacity. And winning takes care of a lot of it.”

Cousy would love to see it. He’s watched a lot of friends die in recent years. Russell, Tommy Heinsohn. He was close with Jerry West, who died in June. Satch Sanders, whom Cousy still talks to regularly, is the last of his teammates from the 1950s who is still around. After the Finals, co-owner Steve Pagliuca left a message on Cousy’s answering machine. Cousy would welcome an invitation to watch the banner raising next season, as long as Sanders and Massachusetts governor Maura Healey, whom Cousy has befriended, can be there with him.

“It’s a special moment,” Cousy says.

And the next one?

“I don’t know,” he says with a laugh. “But I’ll probably be watching from the big basketball court in the sky.”

This article was originally published on www.si.com as The Celtics Define Greatness in Any Era.