Australia’s Tanami desert is one of the most isolated and arid places on Earth. It’s a hard place to access and an even harder place to survive.

But sprinkled across this vast expanse of desert, sweeping for thousands of kilometres across the Northern Territory and Western Australia, are some of the oldest and most incredible stories of human life and settlement of our ancient continent.

It takes the shape of art in the bark of iconic and bountiful boab trees.

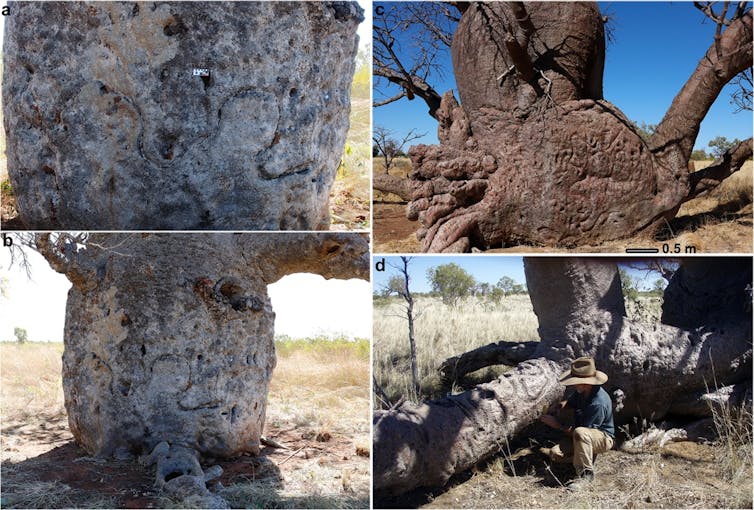

Our newly published research looks at 12 examples of these carved trees across the Tanami desert. This artwork tells the incredible story of the Indigenous Traditional Owners who have long called the Tanami home.

Sadly, after lasting centuries if not millennia, this incredible artwork is now in danger of being lost.

We are in a race against time to document and preserve this invaluable art.

Read more: Iconic boab trees trace journeys of ancient Aboriginal people

Art in the bark

The Australian boab or bottle tree (Adansonia gregorii) is an iconic tree naturally found only in a restricted area of northwestern Australia.

Boabs are an important economic species for First Nations Australians. The pith, seeds and young roots are all eaten, and the inner bark of the roots used to make string. First Nations Australians also used parts of the boab for medicine.

While the culinary and health attributes of boabs are well known, less well known is that many of these trees are culturally significant, carved with images and symbols hundreds, and perhaps even thousands, of years ago. Australian boabs have never been successfully dated. They are often said to live for more than a thousand years, but this is based on the ages obtained from baobab trees in South Africa.

Some hint of the great age of the boabs can be gleaned from the heritage-listed “Mermaid tree” on the Kimberley coast at Careening Bay. “HMC Mermaid 1820” was carved into the tree during Phillip Parker King’s second voyage.

At the time of carving, the girth of the Mermaid tree was measured at 8.8 metres. Today, more than 200 years on, the inscription is still clear and the trunk circumference has increased to about 12 metres.

Now, modern pastoral land clearance and bushfires are having a toll on the oldest of the boabs. There is some urgency to record this cultural and artistic archive before the ancient trees die.

Read more: Built like buildings, boab trees are life-savers with a chequered past

Too often overlooked

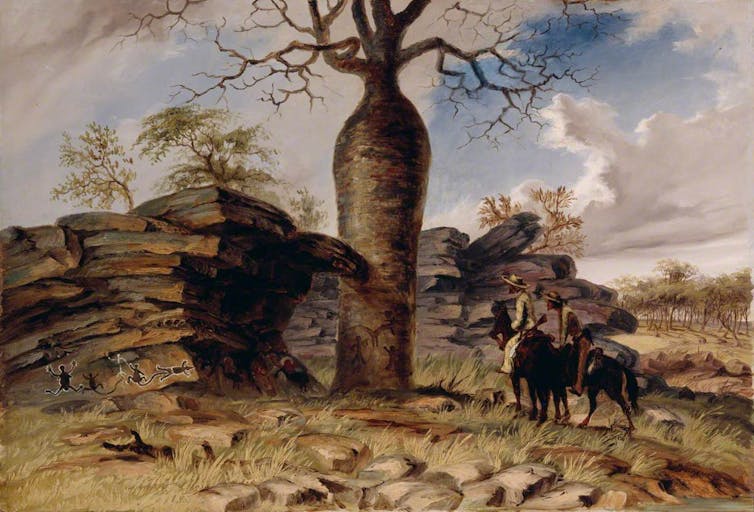

The earliest recordings of carvings on boab trees were made by the British artist and explorer, Thomas Baines, during the North Australian Expedition (1855–56) led by Augustus Gregory.

During the journey, Baines made several sketches of the Australian boab tree, including with Indigenous carved designs.

Despite this early interest, little more was documented about carved boab trees until Ian Crawford wrote The Art of the Wandjina in 1968.

Crawford, a historian at the Western Australian Museum, was primarily engaged in recording the rock art paintings in the Kimberley region. However, on his travels he noted seeing ancient carved boab trees. The Traditional Owners accompanying him made fresh carvings using their metal skinning knives on some of the trees near their campsite.

Almost 20 year later, historian Darrell Lewis stumbled across the Tanami Indigenous carved boabs while searching for a boab tree engraved with the letter “L” marked by the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt on his final expedition, during which he and his team disappeared without a trace.

Our race against the clock

We and our colleagues are now recording and investigating the carved trees.

In July last year, academics and Traditional Owners began to record the boab trees with carvings in the remote northern Tanami Desert.

This area of the Tanami is extremely inaccessible. Finding and checking the trees was a task in itself.

We set up camp among the sand dunes and spent seven days looking for boabs. Although the Tanami is sandy, sharp stakes from burnt out acacia shrubs took their toll. We often spent the best part of the day changing and repairing tyres, or digging the four-wheel drives out of washaways and sand rills.

Once we spotted a boab in the remote distance it was safer to leave the vehicle and set off on foot. We found and recorded 12 carved boabs, but there are hundreds more trees visible on Google Earth which remain to be checked.

Most of the carved boabs recorded on the Tanami trip feature snakes. Indigenous oral tradition describes a major Dreaming track, King Brown Snake Dreaming (Lingka), which begins near Broome and travels east across the Kimberley region of WA before passing into the Northern Territory. Our survey area was located along this track.

Scattered around the base of the larger boabs we found stone artefacts and broken grinding stones, remnant of past First Nations campsites.

The next step in our work is to continue searching for these carved boabs in the coming dry season, and to get radiocarbon dates to establish the age of some of the largest boabs.

These remarkable Australian trees help tell the story of First Nations Australians and are the source of a rich cultural heritage. Through our work and partnership with the Traditional Owners we are rediscovering these Australian stories before they are gone forever.

Sue O'Connor receives funding from The Australian Research Council (SR200200473) and Rock Art Australia

Jane Balme receives funding from Australian Research Council SR200200473, Rock Art Australia.

Brenda Garstone does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.